Dr. Christopher De Bono is Executive Director of Mission, Values and Spiritual Care for Unity Health Toronto. A practical theologian, a clinical and organizational ethicist, and a certified Spiritual Care chaplain, Christopher earned his BA and PhD at St. Michael’s and his MDiv at Regis.

No Shame in Testing Positive for Covid

“No one wakes up dreaming of working through a pandemic!” a good friend once told me, but this latest Omicron wave, with its significant transmissibility and ubiquitous presence, has become a challenge for so many of us health care workers.

Health care workers have the “real world” experience of caring for patients who have tested positive for Covid, while following each and every precaution, including getting vaccinated against COVID-19—the most important action we can take to protect each other and prevent severe disease. We have also been among those testing positive or have been among those exposed through the community.

Hospitals have strong supports in place for staff members who are exposed or who are experiencing symptoms so that they can get tested quickly and stay home in order to keep themselves and our patients safe.

As a senior executive in health care, I know this pandemic is having a toll on our staff, physicians, learners, and volunteers. Health care workers across the province are feeling burnt out, and while we are working to increase mental health supports, I’ve also noticed some people feeling shame in getting Covid even though they’ve followed precautions and are vaccinated. Why?

Almost all of us health care workers do what we do because we care. Wanting to serve and help is in our DNA, part of the age-old culture of being a healer. That is why we might think getting Covid as health care staff means we are letting people down—our teams, our patients.

I admit that when I am waiting for a test result, I sometimes have a fear of “what if”? And if I am honest, somewhere in my head is not only a worry of how badly I’ll get it, how I might not be able to actively work, but a little voice saying “What will people say?” as I believe I have been so careful.

As we all know, voices like that are flags for negative thinking—and not only should we spot negative thinking, we should stop negative thinking—and then think and act differently. At times like this I have had to say to myself, “Christopher, there would be no shame in getting Covid if the test comes back positive.”

There’s another reason not to succumb to shame in getting Covid when you do everything in your power to protect yourself and others. There is no shame in getting Covid because there ought not to be a stigma attached to a virus or an illness. Our history teaches us the harm that stigmatization of any illness can do. Think for example about stigma in HIV/AIDS or in mental health. Shame about getting Covid is an awful burden for healing professionals to have to carry themselves. And so, let me say again: “There is no shame in getting Covid.”

Looking forward, I sincerely hope that today’s modelling and data prove to be true. Trending suggests that this wave has mostly plateaued locally, and we hope that new infections fall as quickly as they spiked.

If you know a health care worker, especially one who has tested positive in spite of every precaution, please thank them for their ongoing service.

We’re all dreaming of waking up to work in a post-pandemic world.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Part of the communications team, Catherine Mulroney studied English and Medieval Studies at St. Mike’s and returned recently to complete an M Div at the Faculty of Theology.

A Shot in the Arm

“Love hurts,” the old song says. But a little short-term pain for long-term gain is always worth it—and especially in these unusual times.

A few days ago, I joined the millions of Canadians now vaccinated. I got a shot of Pfizer and, in the spirit of full disclosure, it didn’t really hurt at all, but for a little site tenderness that lasted all of 18 hours.

My injection moment made me want to recreate Rocky’s famous run up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, or Braveheart’s freedom speech, or Gene’s Kelly’s iconic “Singin’ in the Rain” dance because had been so long in coming and meant so much.

In truth, though, the only thing I did do was get a little teary-eyed because taking 20 minutes out of my day meant I was now one step closer to seeing my children again, a little bit closer to getting back to my real office, and I could now say I was helping in my own small way to end the nightmare we’ve all been living for more than a year. I think I’d forgotten what a pleasant sensation relief can be.

I’m happy to say that my employer, the University of St. Michael’s College, has been supportive as vaccinations have been rolled out, encouraging staff and faculty to get a shot, and offering time off to attend vaccine clinic appointments. It’s a mindset that brings our 180 strategic plan alive for me.

In these days of the coronavirus, I am reminded that the 180 is not just a statement to hang on the wall but a reflection of a lived attitude. The references to such things as concern for the common good, the need to recognize the dignity of all, and our need to care for all creation actually mean something to all of us. Challenging times are bringing that to light. I see this in the professors’ concern for students’ wellbeing, and their understanding that, these days, support and encouragement trumps deadlines. I see it in the student life staff and volunteers’ outreach to students, ensuring they know about extra funding available during COVID or offering reminders to take a break and engage in self-care, informing students of how they can get extra emotional support if needed. And I see it in email traffic and Zoom calls where we are all beginning to realize, via expressions of longing to be together again, that we might all be a little closer than just colleagues.

Daily, I watch the very lessons lived out on campus that I learned in ethics classes while studying theology at St. Mike’s, or while reading the classics here as an undergrad. Life is beautiful and precious and we are called to do our best not only to respect and protect it, but to celebrate it, too. To me, that lesson includes getting a shot—for myself and for my neighbours. We are to live out the now oft-used phrase that we are all in this together. I’m proud to be an alumna—and an employee—of a workplace that practises what it preaches.

As strong as all these motivations are, though, my primary impetus for getting a shot was to ease my kids’ worries. Their dad died a week before the pandemic lockdown began, and the early warnings about the severity of COVID had them stressed about their mother’s health.

“We’ve just had one parent die. We don’t want to lose the other,” said the oldest, soon after the pandemic began, speaking as the now-elder statesman in his usual blunt fashion.

For the following six weeks, I only went as far as our garden, guiltily answering the door on occasions, but mostly watching the world pass by from our front window.

But then, early May dawned, and with it, my first solitary wedding anniversary. I felt an overwhelming desire to visit the garden centre and buy some plants, something that Mike and I had done in May for as long in as we’d been homeowners.

I can’t say it was a fun trip, as it was laden with guilt: guilt for co-opting my youngest into accompanying me on my covert operation, and guilt that I was contravening a heartfelt request from my children. On an up note, though, I felt 17 again, because it reminded me of being in high school and bending a few of my parents’ rules—just slightly, of course.

I monitored dropping age limits and expanding availability and leapt when my chance came. It took close to an hour on hold with the Ministry of Health to book an appointment, and the poor woman who answered my call had a wailing child in the background, but it was all worth it.

My kids put on a brave face at all times for their mother but I know they were relieved. I was just happy I could do something that would ease some of the pile of worries each of them has these days. Then attention shifted to when they could be vaccinated, too, jealous that Molly, the child living in Florida for the year, has already had both doses of Moderna.

This has been an extended period of loss for all of us. Some of the those losses, of course, are trivial—the inability to hit the links, or the discovery that not being able to go to the hairdresser’s means saying goodbye to a preferred hair colour.

And some, of course, are profound. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t lost a friend or relative in the past year, including some to COVID, with their grief compounded by the inability to say a proper goodbye.

That’s why the vaccine, along with continuing measures such as masking and social distancing, remain so important. A shot in your arm is a shot in the arm for all of us. Take one for the team.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Anniversaries are normally a time to reflect, to take stock, and to celebrate. Well, here we are, one year since it became real, since COVID-19 arrived officially at Clover Hill, and remained.

Since last March, I have written and spoken at length in alumni updates, board reports and national university roundtables about both the practical steps and the heroic deeds undertaken by this community; our staff, students, faculty (and alumni and trustees) rose together to face the challenges of this pandemic. We should be very proud of the efforts of each and every member of our community, and when the time comes for us to be together again, we will have much to celebrate.

But though there is light ahead, and I am particularly hopeful these days, there remains much to do. I am especially aware of the inequities this pandemic has exposed, that some members of our community continue to struggle with the myriad impacts of COVID-19 in ways that may not be visible to us. Today, I am thinking about them, and while we prepare for life after the pandemic, we should also be attentive to the quiet voices in our community that look to us not for bold actions, new policies, or press releases, but for understanding and loving support. These are not problems to be fixed, but the relationships that bind this community together and make St. Mike’s different.

So, while you’ve heard me speak frequently and enthusiastically in the last year about St. Mike’s resolve, resilience, and good fortune, my thoughts today are more inclined to what really holds this community together and the blessings we enjoy that never quite find their way into a president’s annual report.

Sometimes, it’s just best to leave it to the poets.

You can have the other words—chance, luck, coincidence, serendipity.

I’ll take grace.

I don’t know what it is exactly, but I’ll take it.

Mary Oliver

In a shifting academic year, St. Mike’s community and creativity keep students engaged

A strong reputation among students, creative, empathetic responses to the pandemic, and hosting some of the most popular undergraduate classes and programs at the University of Toronto have all helped St. Michael’s weather the challenges posed by COVID-19.

“This is a surprising story,” says Interim Principal Dr. Mark McGowan. “We planned for the worst, hoped for the best and were pleasantly surprised. We were dealt an unusual hand and staff, professors, and students responded admirably to the challenges we have been dealt.”

The result, says McGowan, is that enrolment at St. Michael’s has remained healthy, with increases in enrolment in all college courses. This, he says, is due to a number of factors. One is the ongoing popularity of St. Mike’s Book & Media Studies program, which takes an interdisciplinary approach, offering an historical investigation of the role of printing, books, reading, and electronic and digital media in cultures past and present. The program remains one of the most popular at U of T.

Another decision that has kept enrolment numbers strong was St. Mike’s rapid move to online classes, assuring students — and especially international students — that they could continue their education safely from home. At times, this has driven students to discover new interests, as demonstrated by an increase in the number of international students, for example, in Mediaeval Studies courses.

And if students can’t engage in the international travel that is a key component of programs, St. Mike’s has decided to bring the world to our classrooms. In response to the cancellation of the trips that are a key aspect of the popular first-year One seminars, St. Mike’s is creating what is being called a global classroom, allowing students in Toronto to engage virtually with research and data from around the world. Funded in part by a grant from Universities Canada, the global classroom will have dedicated space on campus, complete with cutting-edge technology, to engage with students, professors, and researchers around the world.

The Boyle Seminar in Scripts and Stories, which offers students an interdisciplinary approach to examining the Celtic influences in the mediaeval world, with particular focus on early books and historical artifacts, will be the first to use the concept, partnering with Maynooth University in Ireland. Students here and in Ireland will engage with their peers, accessing digital resources from both universities. With the plan that student travel will resume once travel bans are lifted, the virtual classroom lends itself to any number of courses and programs, as well as a hybrid model of virtual and in-person classes.

Along with the university’s outstanding faculty members, a roster of strong sessional instructors has drawn students to enrol at St. Mike’s courses. In Book & Media Studies, for example, award-winning journalist Michael Valpy has returned to St. Michael’s to teach media ethics while journalist, scholar and activist Emilie Nicolas is teaching a new #BlackLives and the Media course. In Celtic Studies, meanwhile, Shane Lynn is teaching modern Irish History, a course whose numbers have been growing steadily.

But one of the biggest strengths that allows St. Michael’s to remain vibrant is a strong reputation for a student-driven approach, McGowan says.

“Student word of mouth focusses on things like how well the students are treated at St. Mike’s, or small class sizes,” he says.

This academic year has highlighted the care faculty and staff have for students, he says, noting, for example, how impressed he was when he sat in on a regularly scheduled Zoom session, organized by librarian James Roussain, Dr. Iris Gildea and Dr. Felan Parker, for professors to talk about student issues and how best to offer support.

“It is edifying to listen to compassionate professors focussed on being merciful, especially during COVID,” he says.

Underpinning classes and communication is a strong commitment to IT, the interim principal says. To help ensure smooth delivery of classes, the Principal’s Office offered faculty members funding to upgrade equipment to better serve students online. McGowan also credits St. Mike’s IT Supervisor Pio Sebastiampillai , working with the team at the Faculty of Arts & Science, with enabling professors and students to make the best of online learning.

And while in-person events are still not happening, enhanced student experiences continue to happen. This year, for the example, the annual USMC Research Symposium will still take place, online, on Saturday, March 13, on the topic of “Community, Citizenship, and Belonging.”

St. Mike’s also continues to engage with the important matters of the day. For example, the popular Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reading Group, started by Dr. Reid Locklin in 2019, moved online this year so that the university community can learn how it can better engage in the recommend, holding its meeting recently and welcoming everyone to future sessions when they resume in the next academic year.

“St. Mike’s responded well,” McGowan says. “We didn’t panic but worked as a team.”

Mandatory COVID-19 Screening Now in Place

In compliance with the Ontario Government’s “Stage 3” Regulation, and on the recommendation of the Chief Medical Officer of Health for Ontario, the University of St. Michael’s College along with other employers in Ontario is required to conduct employee screening for COVID-19 whenever employees come to work. All employees, contractors, and volunteers coming to St. Michael’s to perform work are required to complete a COVID-19 screening process each time they arrive on campus.

Application has closed.

Results of Screening Questions:

• If you answer NO to all questions from 1 through 3, you can enter the workplace.

• If you are experiencing any symptoms or answer YES to questions 2 or 3, be advised that you should not enter the workplace (including any outdoor, or partially outdoor, workplaces). You should go home to self-isolate immediately and contact your health care provider or Telehealth Ontario (1 866-797-0000) to find out if you need a COVID-19 test. St. Michael’s employees should also notify the Bursar and their unit head.

The completion of this Screening Form is mandatory as a condition of entry into University of St. Michael’s College premises. The data collected will be stored securely and will only be shared as necessary for the strict purpose of support for contact tracing should there be a risk to the University and its community members due to a positive case of Covid-19.

What does community look like in the face of a pandemic? For the Faculty of Theology at the University of St. Michael’s College, community has meant professors digging deep into their own pockets and inviting others to join them to start an emergency fund for graduate students struggling with finances due to COVID-19.

To date, the fund has received more than $30,000 in donations from a small group of professors, staff and alumni and the university has offered to match up to $50,000.

When the pandemic began to take hold, the University of Toronto quickly established an emergency fund for students, but because the Faculty of Theology’s degrees are issued by St. Michael’s rather than UofT, graduate students studying at the faculty are not eligible for the UofT relief funding.

Having been graduate students themselves, however, Faculty professors Drs. Darren Dias and Michael Attridge recognized that their students might be facing any number of challenges, ranging from job loss—particularly tough for single students with no supplementary income—to additional expenses because travel restrictions kept them grounded in Toronto. International students, they note, are not eligible to receive CERB funding from the federal government.

“As soon as [Dr. Dias] reported that students were asking if any funding was available I knew creating assistance was the right thing to do,” Dr. Attridge says.

The two professor chatted and then opened up the conversation to their colleagues. In the broader brainstorming session it was suggested that professors establish a fund to help students unable to help cover costs such as groceries, rent or other standard expenses.

St. Michael’s President David Sylvester received the idea enthusiastically and took it one step further, proposing to match donations up to $50,000 from a University fund.

“The Faculty of Theology is in a position to generously fund many students in terms of tuition, but we do not cover day-to-day living expenses,” Dr. Dias explains. “Graduate students often live close to the poverty line. Coronavirus would only make things worse.”

Doctoral student Mariia Ivaniv agrees.

“It is a challenge for an international student to be alone in a foreign country, but to be alone in a foreign country during the world pandemic is….a huge struggle,” says Ivaniv, who comes from Ukraine. “As a student in such a situation, I was happy to hear about [the] initiative… It shows [the professors’] desire not only to develop the big theological ideas but to practice Christian generosity.

“This kind gesture will help students to overcome a lot of challenges and feel protected and supported.”

Another student, who preferred not to be identified, noted that Toronto is a very expensive city, offering as an example his rent of $1,000 a month for a basement apartment.

“Finances are probably the most difficult thing about being a PhD,” says the student, who was forced to stay in Toronto for the summer, even though his work hours were reduced, due to conditions in his home country.

“Response has been great,” says Ken Schnell, whose regular role is Advancement Manager of the annual fundraising campaign, but who is also overseeing this special project. After the initial donations from professors, the advancement office launched the next phase of the campaign and is reaching out to the wider community of alumni and partner organizations to invite them to contribute. “We are delighted by the generous response, to date.”

“Our students tend to be shy about asking for any kind of help,” says Emil Iruthayathas, the faculty’s Student Services Officer, who is notifying students by email about the fund and how to apply.

Funding will be on a semester-by-semester basis and capped at $2,000 a semester per student. With the $32,000 already received and the matching amount from the university, the fund sits just shy of $65,000.

“Since we do not know how long the pandemic will last we want to ensure we can keep some money flowing to students for as long as possible,” says Dr. Dias.

“This kind gesture will help students to overcome a lot of challenges and feel protected and supported,” says Ivaniv.

For more information or to contribute to the Faculty of Theology Student Emergency Fund please contact Ken Schnell at ken.schnell@utoronto.ca or call 416-926-7281.

InsightOut: Connective Threads

Emma Hambly is a communications coordinator at the University of St. Michael’s College. She has a B.A. in English Literature and Classics from McGill University, and an M.A. in Literatures of Modernity from Ryerson University. In her spare time, she sews, makes collages, designs zines, writes comics, and looks for more hobbies.

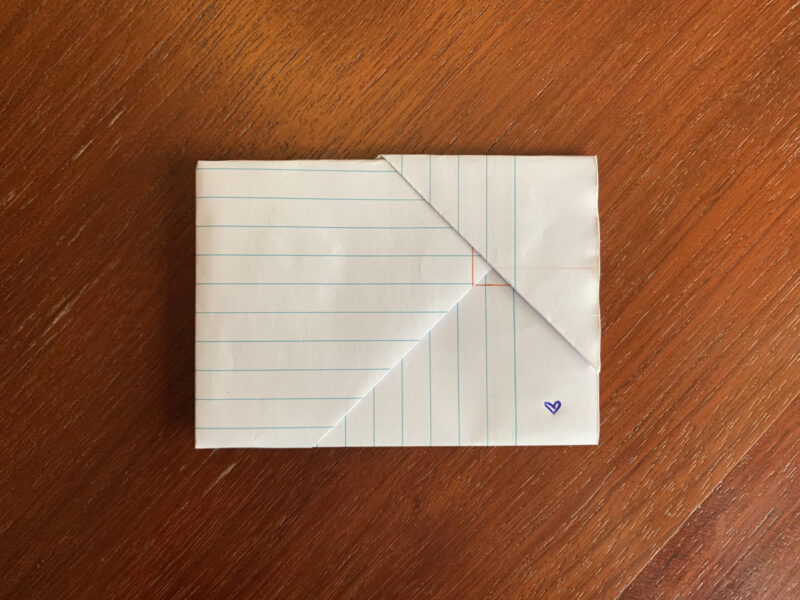

Connective Threads

Push the needle through two layers of fabric, then loop the thread back through itself to make a neat little knot before continuing. It’s a motion I’ve done thousands of times. But during quarantine it’s taken on a new kind of meaning.

***

I’m lucky to be surrounded by very creative friends and family. It seems that most of them have taken the quarantine as an opportunity to take up old hobbies or delve further into their current projects.

One friend is writing again for the first time in years, and another is 52,000 words into her science-fiction novel. My mum is painting more frequently than she has since art school, and my dad is creating collages in the same sketchbook he left half-finished 20 years ago. My best friend is cross-stitching patterns with dainty florals and profanities. My partner is cooking and baking new recipes and continues to feed our temperamental sourdough starter.

As for me, I’ve been sewing. A lot.

Since quarantine started, I’ve been sewing gifts for friends and family and donations for strangers in need. I’ve hand-sewn 16 plushies, embroidered a beret, and made 60 face masks. Our small apartment is bursting at the seams with sewing supplies. My recent online purchases from small Canadian sellers include glass eyes, sheets of vegan leather, metallic felt, and a wonderfully soft faux fur called “minky.” Right now, I’m working on a little bird for my aunt’s birthday and a plague doctor doll because…well, I suppose that one doesn’t need an explanation.

There’s something enormously comforting about a simple task that gives you a sense of control during uncertain times. For me, sewing is a magical combination of enjoyable, relaxing, and creative, a form of self-expression that helps to counteract pandemic-era feelings of anxiety and powerlessness.

My mum, who is a talented seamstress, taught me how to hand-sew when I was six. And since then, the slow but sure process of turning a few pieces of fabric and some thread into a three-dimensional object with its own personality hasn’t stopped enchanting me.

Quarantine may be filled with necessary constraints, but it has let me pursue my hobby unrestricted.

In the earlier days of the pandemic, I volunteered for Stitch4Corona, an initiative organized by U of T Engineering students to provide fabric masks to Torontonians in need of them, like seniors and the unhoused. With access to a sewing machine and basic skills, it felt like the least I could do. When I was able to expand my social bubble to include my parents, my mum offered to help.

Sitting at the dining room table on a rainy day, listening to the whir of the sewing machine, took me back to my childhood, watching my mum make my Halloween costumes. Year after year, she would create an impeccable, real version of whatever I had dreamed up: a furry tarantula with eight interconnected arms, a red rose with my face peeking out of the petals.

This time, though, we were working together. I sewed the fabric into its basic mask shape and stitched in the elastics. My mum gave each rectangle three neat pleats, and I finished the sewing, adding in the nose wires and leaving pockets for filters.

We switched, laughing, when we realized she had accidentally pleated all the masks so far upside-down, and I was much slower at topstitching. We found our rhythm and spent the afternoon turning a pile of fabric sheets, elastic, and wire into a thick stack of masks.

Before I could start my third round of sewing, Stitch4Corona announced that with COVID cases decreasing in the city, they were wrapping up their initiative. In the end, more than 600 volunteers sewed more than 14,000 masks.

I turned back to my lifelong hobby, sewing by hand.

When quarantine started, I felt caught up in the need to do some small thing to let my loved ones know I was thinking of them. So, I bought two pattern collections (32 designs in total), sent the images around to my friends and family, and asked them to pick their favourites. I’m about a third of the way through the list.

I’m worried about my grandmother’s wellbeing and I haven’t been able to spend quality time with her in months, but I’m glad to know she keeps the little raccoon I made her right next to her computer. My friends’ faces lit up when they picked up their creations at our 6-feet-apart, masks-on barbecue.

It makes me happy to create something tangible for my friends and family when our connections these days are so digital. And I hope my silly plushies can bring them a smile in these strange, stressful days.

Time, effort, and connective threads. Put simply, sewing is the art of bringing things together. Sometimes, it can have that effect on people as well.

Read other InsightOut posts.

The University of St. Michael’s College is preparing for a gradual, safe return to campus guided by the advice of public health authorities, UofT processes and protocols outlined in UTogether 2020: A Roadmap for the University of Toronto and within the framework of the following principles:

1. St. Michael’s staff and faculty should work from home whenever possible, and campus offices will remain closed until further notice. Staff and faculty whose functions require their presence on campus will be provided approval by their department managers to work on campus based on capacity, need, public safety guidelines, and UofT policy.

2. Deans, directors and department managers (or their designates) are responsible for ensuring their staff and work spaces align with COVID-related protocols. This includes:

- providing approval for, and tracking, employees and faculty who come into the office and coordinating efforts to ensure safety in spaces be shared by multiple departments

- contacting Facilities to request replenishing of PPE and sanitization materials as required

- following UofT protocols should one of their employees/faculty be diagnosed with COVID-19

3. St. Michael’s, like all UofT campuses, will follow the University of Toronto Policy on Non-Medical Masks or Face Coverings and draft guidelines. To support UofTs policy on non-medical masks, St. Michael’s will provide staff, faculty and students with two reusable, non-medical masks. St. Michael’s department managers will provide their employees with their two reusable, non-medical masks. St. Michael’s employees will be responsible for cleaning their own masks, and providing their own face coverings if these are lost.

As the fall semester approaches, the University of St. Michael’s College is implementing cutting-edge measures—including some from front-line health care settings—to keep the campus safe for community members and visitors.

“Safety is of foremost importance when considering reopening—not just for staff and students, but for everyone that has access to USMC,” says Michael Chow, Director of Facilities and Services at St. Mike’s. Following public health guidelines and the University of Toronto, Chow and his team have implemented measures ranging from extensive cleaning strategies to high-tech virus-killing devices. The measures fall into three main categories: facilities, administrative measures, and personal protective equipment (PPE).

Facilities

Visitors to campus will notice a variety of newly installed safety measures this fall, including Plexiglass shields at key points including the Porter’s Desk, Registrar’s Office, and other areas where queues could create challenges for physical distancing. Classrooms and common areas will have less furniture and reduced capacities in order to make it easier for an appropriate distance to be maintained, and signage and stickers will help direct pedestrian traffic to keep people moving efficiently and safely through indoor spaces.

HVAC equipment will receive increased–efficiency filters wherever possible, as well as a more rigorous filter replacement schedule to ensure clean air throughout campus buildings. Twenty-five free-standing hand-sanitizer stations have been installed next to building entrances, high-traffic areas and entrances to larger classrooms, and wipe or spray disinfectants will be available for students to quickly clean off a desk or chair before they use it, as well. All washrooms are now stocked with paper towels, and Legionella testing has identified no issues with water on campus.

Administrative

“I think the most important change is about our cleaning strategies, for both common spaces and student spaces,” Chow says. In line with UofT’s tri-campus cleaning protocols, St. Mike’s will conduct enhanced cleaning throughout all building spaces and student areas while also adding “a dedicated team of cleaners to do disinfecting and increase cleaning in high-touch areas—a minimum of twice a day for high-touch surfaces.” Routine cleaning during normal workday hours as well as on nights and weekends will be enhanced through the use of new cleaning agents, which have been upgraded to a dual-purpose cleaner that both cleans and disinfects.

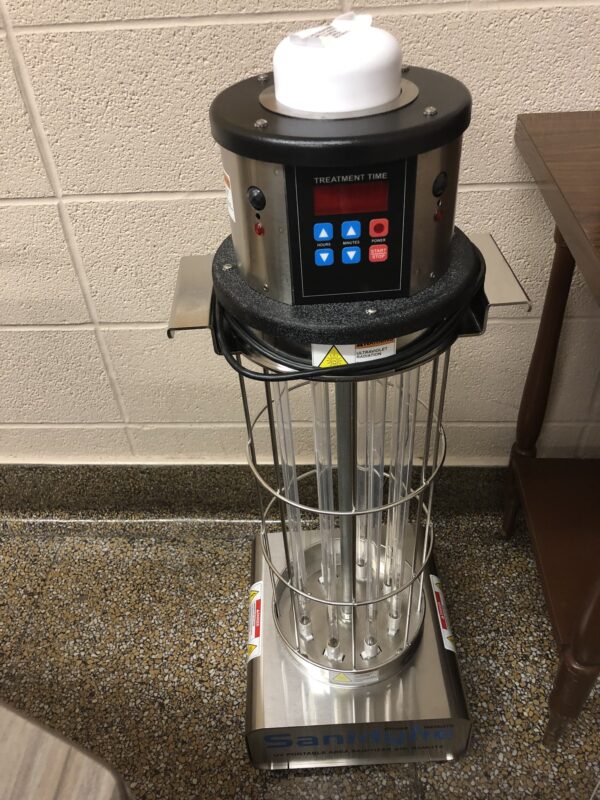

Hard at work keeping campus safe since the pandemic began, the Facilities and Housekeeping teams is going into the fall semester with new, high-tech tools. Chow says that his team adopted some of these after first seeing them used in hospital and long-term-care settings—the front lines in the fight against the virus.

These tools include a stand–alone UV light system, which staff are using to disinfect all residence rooms before new students move into them in September. The portable UV system is also intended for use in classrooms. A hospital-grade portable disinfectant misting system will also be employed on an as-needed basis, helping to disinfect places that are hard to reach using normal cleaning methods.

PPE

All Facilities & Services staff members have worn either reusable or disposable masks during their work since the pandemic began, with many of those coming from a generous donation of 2000 masks by a St. Michael’s student in May. Now, as some staff and faculty return to campus this fall, two reusable masks will be provided to every student and employee. St. Michael’s will follow the University of Toronto and the City of Toronto in requiring non-medical masks or face coverings to be worn inside buildings that are normally publicly accessible.

Anyone without one will be able to receive a single-use mask at the Porter’s Desk, ensuring that all outside visitors and contractors will also be able to have access to masks while on the USMC campus. Signage posted throughout campus will provide visitors and community members with reminders of proper mask usage as well as principles of handwashing, correct hand sanitizer usage, and other important safety principles.

Behind all the safety measures being implemented on campus, Chow says, are the members of the Facilities and Housekeeping teams, whose tireless efforts have kept students, employees, and visitors safe throughout the pandemic. As he wrote for InsightOut, “Behind the scenes—and often unnoticed—the F&H staff have faced the challenges of the pandemic as essential staff and turned them into opportunities as guardians for the university.”

“I think we’re doing something right,” Chow says. While the safety measures will help keep the St. Michael’s campus safe this fall, he notes, it’s almost just as important to communicate the changes to the campus community “to put everyone’s minds at ease.

“We’re not just sending everyone back to the same university they left,” he says.

Consult Fall 2020 for current updates on St. Michael’s plans for the fall semester.

Isabella Mckay is a senior student majoring in Book and Media Studies at the University of Toronto. Following her passions in marketing, communications, technology, and media, she has become the Vice President of TechXplore, the Director of Marketing of Data Science Toronto, and the Assistant Project Coordinator at the University of Toronto Faculty of Arts and Science Dean’s Office. Mckay looks forward to applying her passions and work to innovate the future.

Love and Happiness as True Measures of Life

During the coronavirus pandemic, I have discovered that the principles of humanity, which are love, togetherness and health, exist as the ultimate purpose and meaning of life.

On January 27, 2020, the National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg confirmed the first case of coronavirus in Toronto. Remembering the words of my mother to not fear and panic but be prepared and cautious in case of emergencies, I bought one of a few alcohol rub left at a pharmacy in Toronto. At my condo, I found one pack of 20 N95 masks for around 85 dollars with express shipping on Amazon. Although I could search for cheaper masks, future prices would likely increase, and then I might search longer to find no masks and sacrifice my health. I would work to recoup the price within hours; however, I would spend more time and energy to regain what was most important, my health. I purchased the N95 masks within three minutes.

When coronavirus cases rapidly increased after February 24, I had the proper procedures and supplies to calmly protect myself from the coronavirus while others began to panic. I still socialized with friends, studied at the libraries, and attended club events at the University of Toronto.

Then, the University of Toronto announced that, as of March 16, it would close, and move to online courses and examinations to limit coronavirus cases. I wore my N95 mask as I walked around the campus and a downtown Toronto that resembled an abandoned town devoid of energy and emotion.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, I huddled in a tight and quick one-way line of students to attend my classes on time. Now, I freely and slowly roamed past three students on my way to the library. I used to walk around for five minutes to find an empty library seat and to hear pencils and pens scratching on paper during midterm and final exam season; now, however, I found an empty seat and heard the hum of the air conditioner as soon as I walked into the library. I used to sit next to students who flipped through pages of homework, wrote mathematical equations and assignments, and coded programs. As I sat in one of the hundreds of empty seats, I remained two metres or more from other students because of my own preferences or because of tape placed between every two desks and in front of desks.

With the cancellation of on-campus classes and exams, I returned to my family home in Vancouver on March 21. Although the Canadian government did not require citizens to self-isolate on a domestic flight, I feared that someone might have coronavirus on the plane. I wanted to ensure that I had no symptoms and that I would not transmit the virus to family. If I transmitted the virus to my family, I would fail to mend my shredded heart.

Although I talked to my family and friends through my phone during isolation, I became an outsider who might have a disease that everyone feared. I yearned to be near my loved ones, especially my family who sacrificed their time and health to care for me. I did not want, and was not motivated by, my empty university scores and jobs, which for years I had desired most; instead, what I wanted and was motivated by was familial love and unity.

Once I left self-isolation, my family revealed that they struggled to obtain essential groceries and supplies. Before the coronavirus, my family and I might spend half an hour choosing organic and natural vegetables among full shelves. Now I wore ski goggles, plastic gloves and a N95 mask as I social distanced to purchase any supplies at a local grocery market.

Similar to food and supplies, before the coronavirus stole the simplest moments, I took daily and normal activities for granted in order to pursue my career and high marks. I carelessly walked, compared to now seeing someone and moving to the other side of the road. I carelessly talked to others, compared to now yelling over two metres to discuss the coronavirus lockdown. I carelessly socialized with friends compared to messaging them. I carelessly went anywhere to perform multiple activities compared to restricting myself to my home and grocery trips. Appreciating people and the simplest things are blessings of happiness. I am not measured by what I have, but who I am and how grateful I am to have what I have.

Once the lockdown ends, I will refuse to let fear control my life and I will experience the meaning of life: to be around loved ones and increase happiness activities. When will I get another chance, and who foresees the future?

The coronavirus pandemic has taught me how health is the most important quality and how everything else is minor, how people, and the smallest and simplest things, deserve appreciation, and how love and happiness are true life measurements. These essential human qualities are the purpose and goals of an amazing life and these human foundations will support the fight to defeat the coronavirus.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Martyn Jones is a content specialist in the Office of Communications. On a freelance basis, he also writes reported features, essays, and criticism for online and print outlets. Martyn and his wife Melanie’s toddler, Fox Jonathan Jones, turns 18 months old on August 2.

The Difference Three Hours Makes

In the endless domestic present brought on by COVID-19, I sometimes find it difficult to remember that going to work once meant going in to work.

A few months ago, my wife and I would kiss our toddler goodbye, trudge through the snow to a bus stop, and wait to be carried into the city alongside thousands of fellow close-breathing commuters. It was far darker then, and both our bedtimes and alarms were earlier. In the mornings we’d wake the baby around 6:30 a.m., pass him back and forth to allow one another to get dressed and brush our teeth, and then hand him off to his grandparents around 8 a.m. for safekeeping for the day as we began our commute.

During my wife’s maternity leave, I would often look down from my computer screen in my office to find a message from her that included a photo or video. These were digital records of Fox’s progress: first words, first steps, first instances of bizarre behaviours that would become characteristic. When my wife returned to work, she would forward similar notes from her parents containing records of Fox’s new experiences that we were both missing.

After work, we’d get home around 6 p.m., scramble to put Fox’s dinner together, play with him if time allowed, and put him to bed by 7:30. Our total allotment of time with the boy was about three hours a day—most of it spent performing necessary tasks, and relatively little spent in reading, play, or exploration.

When remote work began for both of us in mid-March, we entered into a family bubble arrangement with my wife’s parents, who continued to provide our toddler’s primary care during the workday. For the last several months, we’ve worked with Fox always within hearing distance, either downstairs in our own home or in another room at his grandparents’ house.

We are incredibly fortunate to be able to rely on our toddler’s grandparents in this way. For so many younger families, the closure of childcare centres and schools forced parents to look after their children while also continuing to work full time. We were shielded from this grueling scenario. For us, the silver lining has made up almost the entire cloud.

Atul Gawande notes in his book Being Mortal that one of the major domestic shifts brought about by modernization is the move away from multigenerational homes. The past few months have given us glimpses of that abandoned paradigm: during a break between tasks, I can join Fox at the keyboard where his grandpa is preventing him from striking the keys too hard, or peel an orange while listening to the toddler perform his mimicry of reading out loud for his delighted grandma.

He is a wild and energetic boy; his arms already have a shape that evokes the naturally athletic teenager, and as they grow will gain mass while retaining their rough proportions. He occasionally gets away from his grandparents and pounds on our office door until it opens for him, at which point he might walk to my desk, look at me silently, throw back his head, and laugh. While he’s interrupted his share of Teams meetings, my colleagues reassure me that his presence has always been welcome.

I have no truck with vulgar permutations of utilitarianism, the worst of which employ an actual calculus to determine the moral worth of an action, but I do find it useful to put a number to our experience: 270. This is a rough estimate of the number of hours my wife and I have gained back to spend with our boy during the portions of the day we would otherwise have spent commuting or having lunch at work. Our three-hour allotment has doubled for each workday, without even taking into account the random visits he pays us as we hunch over our computers.

Instead of receiving photos or videos through text or email, my mother-in-law can simply call me to come down, and I can be there to see my boy build a block tower or put on his own shoes. We haven’t yet reached the point at which his long-term memories are able to take root in his mind, but I hope that he will carry this period of special nearness into the later parts of his childhood, and know without knowing that we were close by.

For all the uncertainty and hardship brought on by the pandemic, COVID-19 has also shown us how flexible the world can be when the heat of necessity causes it to bend. There will not be a return to an earlier status quo after the virus subsides or vaccines are developed: instead, a new world will emerge. I hope that our new arrangements will make future virtues of past necessities, and that it will be possible for more working parents to experience the difference three hours makes.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Giancarlo Mazzanti is the Registrar and Director of Student Services at the University of St. Michael’s College. Giancarlo is a graduate of the University of Toronto (St. Mike’s) with an Honours B.A. in Political Science, and a B. Ed. from the Faculty of Education in 1985. He began his career in education at St. Michael’s College School and has worked in student services for over 30 years.

Our Connection Is Just Fine

It’s not like rumours weren’t swirling about a possible move to a primarily online mode of delivering the services of the Registrar’s Office and related Student Services. So it was with the better judgment of our team that we began preparations for what was beginning to look like the inevitable. It seemed like no time at all passed from those water cooler conversations with colleagues within the university community to when the email arrived from the Office of the President telling us that our offices were closing to in-person services. Academic advising meetings, learning strategist sessions, wellness appointments, and every other function and/or service would need to go online.

We received the call on the afternoon of March 17. Within minutes, Morteza was making sure e-tokens were good to go and that college staff in the various university offices were able to log in from home. Most were taken care of, but there were still a few to activate: no problem. Miranda, with Guillermo’s and Philip’s help, was making certain all students on the day’s docket were either seen or given a new appointment, all while planning for graduation scholarships and any number of the other responsibilities within our office. Nawang was ensuring that bursaries were going to get into students’ hands… yesterday! Next was getting ready for the hundreds of financial aid requests that would be submitted by our students, as well as the upcoming round of May admissions. Stephen was finalizing plans on how we were going to meet with future applicants, remotely, all while he and his wife were getting ready to deliver a future SMC student. Judy and Alex? Well, the newest members of our office were getting ready for the onslaught of student advising appointments which would fall on their shoulders as the various portfolios were being tended to. Hundreds of emails daily! Then, as the day turned into evening we packed our favourite mugs and our laptops and, with e-tokens in hand, we went home to our new offices!

All were confident as we prepared for remote delivery, even though the occasional nervous giggle could be heard. Gone were the commutes, the traffic, and the aggressive drivers. So was that horribly conspicuous dash to the only open seat on the train; everyone knows when you have designs on a seat in a subway train at 8:15 in the morning! Now it was simply a 12-second climb to the second-floor office, right next to the bathroom, and with a lovely view of the garden.

And so it was that practically overnight all university operations moved online, except for the staff in finance, the residence operation, and building services. They were our “hyflex” model pioneers. They were toughing it out on campus to make sure that USMC kept functioning and that students unable to get home had a room on campus, and that it was a safe space. The I.T. department stood on its collective head to make sure we had the hardware, software and in-servicing on the technology we had all dabbled in but which was not yet part of the daily menu. All of a sudden, Teams and Zoom were the plat du jour! And of course, the Communications team made sure there was an uninterrupted flow of information, essential to all parts of the community.

By the end of Day One of working from the home office, in whichever corner of the house we were assigned—or had earned over many years of squatting—many of the bugs had been worked out. It was quickly becoming business as usual for most, with the rest not far behind. Professionals who were accustomed to meeting in person were now looking at a screen with nothing more than a student’s initials in a small circle. Whether discussing course selection, scholarships, or convocation, all meetings were now being conducted via telephone or in a Teams meeting. Different delivery models, same great advice and suggestions.

And how appreciative our students were during those early days of the new, even if only temporary, normal! Every email or call we received began with “sorry to bother you during this very busy time,” and was often followed up with a lovely thank-you note.

Today, after hundreds of Teams or Zoom advising meetings, thousands of emails, dozens of website updates, countless online lectures and tutorials, governance meetings, a virtual Welcome Day for newly admitted students, two new Quercus courses to help transition our class of 2024, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in emergency financial aid to our students, it dawned on me. I confirmed for myself what I knew all along. The people! That is the ingredient that is making all the difference.

The people I met on campus were important to me during my undergrad years, decades ago, and I understand far more clearly how important that is today: the staff, faculty, and students of the university. In these “interesting” times, we know we can rely on each other. Whether teaching or making sure we are well positioned to tackle the financial pressures of the coming year or helping a student find a course that will fill a final breadth requirement, we know each member of our community continues to do their utmost to make things work for our students—and for each other. I am confident that is why we were all drawn to this place, our community. That is why we will be ready for the coming year. Yes, a simple electronic screen will not get in the way. Our connection in just fine.

Read other InsightOut posts.

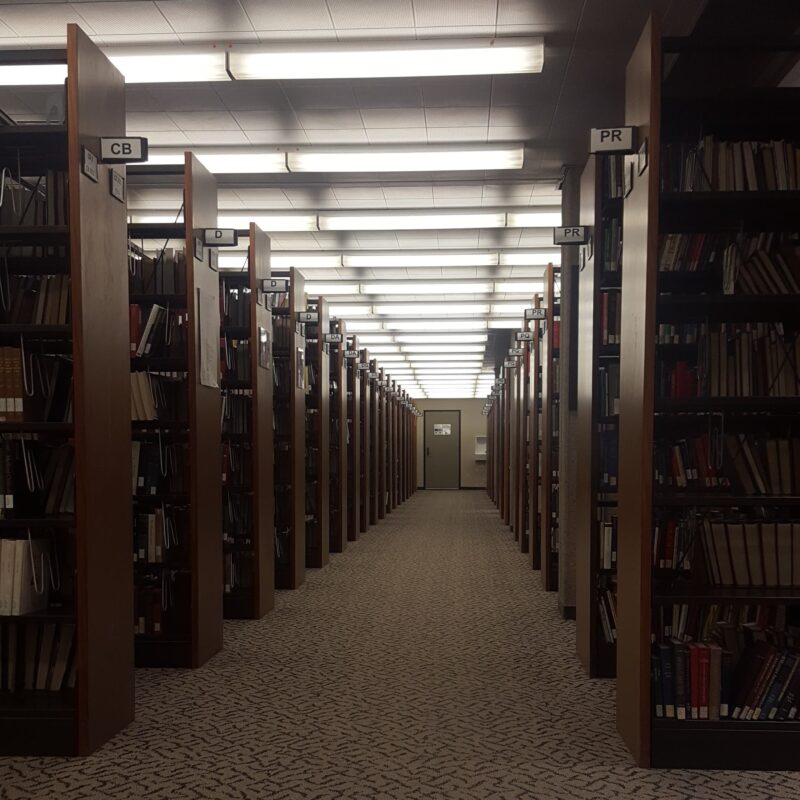

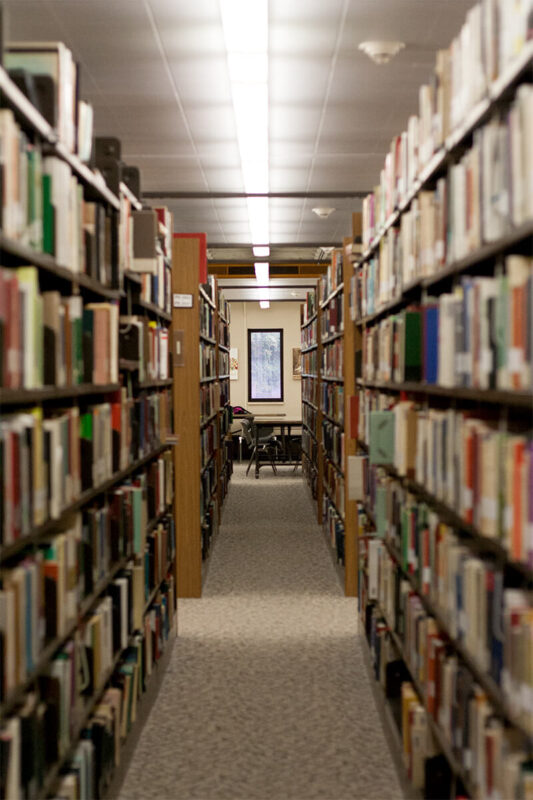

Kelly Library patrons can once again hold physical books from the collection in their hands through a new curbside pickup service.

To support the community’s access to materials while also following public health guidelines, library staff can now accept requests from any patron with a valid UTORid through the UTL catalogue for select physical items in the collection that are not held in the Hathitrust Digital Library. These items are then made available for pickup in a safe and appropriately distanced manner.

“Curbside pickup of materials is an exciting move toward reinstatement of our services and in our ongoing effort to support students and faculty,” Chief Librarian Sheril Hook says. “As we launch and evolve the service, the health and safety of our community is a top priority, with safety precautions implemented at each step of the borrowing process, following guidelines outlined by the University of Toronto Libraries and Toronto’s public health authorities.”

After they receive a pickup notice from library staff, patrons can visit to pick up materials between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. Monday to Friday in front of the library. Visitors using the service will queue in a waiting area and then proceed to approach the window near the book return slot under the awning of the library, and boxes marked with tape on the ground will indicate where patrons should wait in order to maintain a safe physical distance. The library will not be open to visitors indoors, and all pickups will be handled outside. Patrons who cannot come in person can place a note in the catalogue request for their friends or family members to pick up materials for them.

The service makes available materials that have otherwise been inaccessible to patrons in any format during the pandemic. In addition to the physical items now available for curbside pickup, patrons can request a PDF scan of a single book chapter or journal article from the library’s circulating collection not available through Hathitrust. Physical items being lent out will be due back by August 31, 2020, although this date may be updated as plans continue to change during closures.

The Kelly Library has made available full instructions for using the service, including health and safety guidelines and FAQs.

Jessica Barr is the University Archivist and Records Manager for the University of St. Michael’s College. She is a graduate of the University of Toronto (New College 0T9, Faculty of Information 1T1), and spent much of her time as a student studying in the John M. Kelly College Library. Not much has changed, except her desk’s location in the library.

Archiving St. Mike’s in Quarantine

The University of St. Michael’s College Archives is tucked in a corner of the third floor of the John M. Kelly Library. The Archives preserves the official records of the University, including records from the offices of the President, Principal, Faculty of Theology, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, and Continuing Education program. We also have papers from faculty, records about some alumni, student publications, and an extensive collection of photographs. More recently, I’ve written a survey to capture the experiences of our community during the COVID-19 pandemic (but more on that later).

Much of my time includes hands-on work with the paper records that contain the history of St. Michael’s College: I arrange transfers of records from donors, I make sure the archival materials are properly housed so they can withstand many of the tests of time (including damage from light, pests, or mould), and I create digital inventories with written descriptions of the materials so they can be accessed by researchers. I also respond to reference requests from researchers near and far—some are looking for information on alumni who attended St. Michael’s, some are conducting academic research using papers written by faculty, and some are simply interested in our history as an academic institution.

Since mid-March, however, I have been working remotely, like many of my St. Michael’s colleagues. So how do I archive materials without physical access to the archives? With the help of the IT departments at St. Mike’s and the University of Toronto, I have been able to maintain access to my network drives and my digital records. These records include my digital inventories of the collections held in the archives and more than 1500 digitized photographs. This means I can continue to respond to many reference questions, including a recent query about the date the clock was added to the Elmsley Hall tower. (It was 2005, in case you are wondering.) I can also update inventories and spreadsheets to make them more accessible for future users, or upload them to the website; update policies and procedures; coordinate with colleagues on questions related to records management; finally clean up my hard drive; and convert already digitized materials to more usable file formats.

During this time of quarantine and pandemic, I have been wondering how the archives can preserve this point in history. I find myself asking: What do I wish we knew about the 1918 pandemic at St. Michael’s? What was that period like for our students, staff, faculty, and alumni? We are able to gather some information from administrative records and yearbooks, but we don’t have very many first-hand accounts. In response, I have been actively archiving the digital records created by the administration over the past three months, including public emails and the St. Michael’s website. In an attempt to gather eyewitness accounts of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have also written a survey to send to our community, with the goal of capturing information about our thoughts, feelings, and experiences. In the future, researchers will be able to access these answers to learn what life was like for us during this particular moment.

We invite you to submit your own answers to the survey, and any photographs that capture this moment: https://stmikes.utoronto.ca/usmc-archives-and-covid-19/

I’ve copied examples of my own answers below:

Name: Jessica

What is your current location: My kitchen table, Pickering, Ontario

How are you connected to St. Michael’s College? Staff

How have you, your family, and community been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic? I have been working remotely since March 12th. A few immediate family members were temporarily laid off from work, but the rest have been working remotely. We have all, thankfully, remained healthy. Many of my neighbours have been home, so we see a lot more people on walks now.

Share your experience with teaching, learning, or working remotely: I was able to begin working remotely very early on, thanks to previously-set-up off-site network access, and troubleshooting with our IT teams. Transitioning to Zoom or Microsoft Teams meetings was a bit of a challenge, since not all colleagues immediately had access to a camera or microphone. After a couple of weeks, though, we all got into a “normal” swing of things. I have really enjoyed meeting the pets and children of colleagues via web meetings.

What about your routine has changed? My gym is closed, but is offering Zoom classes to keep active. I just noticed that my bus line to get to the GO station has been shut down due to lack of ridership, so that will be a challenge when we’re cleared to physically go back into work. Beyond that, I’ve been reading a lot of cookbooks and testing out a lot of new recipes. Luckily, I have family nearby, so I can deliver some treats to nearby porches. I would normally have a day each month to visit with my father (who lives about six hours away), but we haven’t been able to travel since February.

For more information about the University of St. Michael’s College Archives, please check out this link: https://discoverarchives.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/university-of-st-michaels-college-archives

Please email me you have any questions for the archivist: usmc.archives@utoronto.ca

And, if you’re interested in seeing digitized copies of historical St. Michael’s yearbooks, you’ll find some here: https://archive.org/details/usmichaelscollege

Read other InsightOut posts.

Dr. Darren Dias teaches in St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology, specializing in Trinity, Religious Diversity, and teaching methods. He is currently working of a SSHRC funded project with colleagues Gilles Routhier (Laval) and Michael Attridge (St Michael’s) entitled: “One Canada, Two Catholicisms: Divergent Evolutions in the Catholic Church in Quebec And Ontario, 1965–1985.”

When the Monastic Cell Meets a Zoom Meeting

When someone enters a religious order or institute for consecrated life they begin with the novitiate. Monastic orders like the Benedictines, Cistercians, and Trappists, mendicant orders like the Franciscans, Dominicans, and Carmelites, or apostolic congregations like the Basilians, Sisters of St Joseph and the Lorettos—everyone begins in the novitiate. This is an intense period of no less then twelve months when the novice is removed from his or her normal life and confined to the novitiate community. The novice leaves behind his or her job, or studies, and the comfort of one’s usual network of relationships, and enters into something new. One is suddenly disconnected and inserted into a foreign reality. Novitiate is the beginning of a process of formation into a particular history, charism, spirituality, theology and way of living.

My novitiate was spent in the Priory of St. Albert the Great in Montreal. The large priory was built to house about 100 friars in 1960 (just before the exodus of so many religious). The complex includes a large conventual church, refectory, community rooms, ‘cells’ (bedrooms), pastoral institute, administrative offices, even a pharmacy, swimming pool and its own postal code. Although on the campus of the University of Montreal, St. Albert seemed like an oasis in the midst of the hustle and bustle of urban university life. One could easily survive without leaving the complex for weeks, maybe months.

St. Albert seemed to have preserved much of the medieval character of the Order of Preachers: a separate choir for the religious in the chapel, long refectory with an alcove for the reader, silence in the halls, habited religious moving from choir to refectory, etc. The rhythm of my day unfolded according to the schedule of the liturgical hours (prayers): lauds and Eucharist in the morning, mid-day prayer, and vespers; after each hour, the appropriate meal was served. Between prayer and meals there were blocks of time for contemplation and meditation (naps); study, common and individual; and work, on-site labor to meet the needs of the community (cleaning, gardening, snow removal, etc.).

The imposed confinement in March due to COVID-19 has felt in many ways like a return to my novitiate experience. The rhythm of life that developed in the wake of the confinement was not unfamiliar. My life was not punctuated primarily by apostolic activities—teaching, lectures, parish ministry—but around common prayer. Always being home has meant that morning or evening activities no longer make it possible to skip common prayer for a different “priority.” Of course, through technology many of activities continue, but in drastically different ways. The sacrosanct private space of the “monastic cell” has been displayed on Zoom for all to see.

For centuries, religious have in some way retreated from the world, for love of it, into a voluntary confinement. Withdrawal means making space for the other, especially for the most vulnerable and in need. This is not a space of escape from the world, but a space of intimate encounter, where the “joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties” (Gaudium et spes) are appropriated and placed before the Triune God in prayer. Since COVID-19 began, this prayer has been mottled by petition and supplication for healing and reconciliation.

Religious communities, even ones rooted in monastic or medieval notions of “separation from the world,” are not unaffected by pandemic. In 1918 Archbishop Paul Bruchesi of Montreal wrote a pastoral letter praising the work of many religious communities during the Spanish Flu epidemic. Apostolic religious communities were on the frontlines of health care and social assistance then. In these twilight years of religious life in Canada, religious communities experience solidarity with the victims of COVID-19 differently. Less than directly serving those most affected by the pandemic, many religious have become its victims.

If religious communities were aware of their vulnerability before the pandemic, how much more keenly are they aware of it today? In 2014, Canada counted about 11,600 religious. Of that number 50% were over 80 years old and 44% between the ages of 60-80. Already in 2014 fully 25% of all religious lived in long-term care homes. Many religious communities have been devastated by the coronavirus. In Ontario, the Jesuits temporarily shut down their retirement facility. Half of the residents in the Residence-De-La-Salle, a mixed religious community care facility in Quebec, have died. Some religious communities have lost up to one third of their members due to COVID-19.

My return to my novitiate experience, coupled with the witness of those who have been affected by the disease, reminds me that religious life is an ongoing process of becoming ever more vulnerable. A voluntary confinement does not separate religious from the world around them, but brings the vulnerability of that world into the heart of who we are.

Read other InsightOut posts.

June 8, 2020

Dear members of the St. Michael’s community,

I trust this message finds you in good health and holding up in these uncertain times. The 2019/2020 academic year has ended like no other, and I have watched our community respond with grace, courage and resilience to the challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Once again, St. Michael’s is showing that even in very difficult times, our strength and generosity marks us as an anchor of hope in our community.

Social media use of #allinthistogether has gathered traction as the world responds to COVID-19, but I am particularly struck by how, at St. Mike’s, we really are in this together. Together, our students, faculty, alumni, and staff have worked to respond to these unique times, enabling classes to continue while ensuring the safety and security of campus, and the community. Students have been particularly resilient, and they have shown great understanding and patience in the face of a dramatically upended school year. As I look forward not only to the coming academic year but also to the future of St. Mike’s, I am confident that the lessons learned in these challenging days will help strengthen this incredible place, a place with compassion and community at its very heart.

When it became clear in mid-March that we needed a drastic response to the looming health crisis, creative problem-solving swung into action across the University. Within days, faculty and staff began offering classes and advising remotely, and students rose to the challenge. Residence students were able to pack up and head home early. The library remained open online, even offering a town hall on research. With a dedicated skeleton staff on campus to ensure that our students who could not leave were safe and supported, colleagues began working remotely, and virtual meetings became the norm. For the first time in history even Collegium and Senate meetings moved online.

This period will forever be remembered as a time when the world faced challenges above and beyond the norm, and we offer our support to those who are suffering. For St. Mike’s, the pandemic has forced us to sacrifice some much-loved traditions. We had to cancel spring reunion on campus and move to online anniversary activities, and the Class of 2020 missed out on an in-person, on-site convocation. As always, however, our community has responded with energy and hope. Whether it’s our Student Life team working on a virtual orientation for the incoming class, staff in the Registrar’s office taking additional time and care to respond to new and returning students’ concerns, or one of our students arranging to donate thousands of masks to protect those still on campus, this community is motivated by a concern for others, and it has been deeply moving and inspiring to witness.

We were in the midst of our St. Mike’s 180 planning when the pandemic hit. The pause in this project has allowed us time to reflect on our efforts to date and has affirmed what we already knew, that it is the strength of this community that is helping us weather this difficult storm and gives us hope for the future. We remain focused on our plans for renewal and I look forward to restarting conversations with you all about who we want to be as an institution and how we plan to achieve that. Obviously, we are stepping into a very different world, but St. Mike’s is prepared and must take up the mantle of leadership and think of new ways to build hope for our university and society, through our academic and student life programs and through our alumni and community partnerships.

Looking ahead to the 2020-2021 academic year, much remains unknown and difficult decisions must be made in the face of ongoing uncertainty. The health and safety of our community continues to come first, as well as the ability to reopen and resume operations when we are able to do so safely. The university is also facing challenges with regard to reduced revenues, and must also ensure that it remains fiscally sustainable. In early April, we implemented a hiring freeze, along with temporary redeployments. More recently, faced with prolonged shutdowns of parts of our campus and operations the University has worked with the United Steelworkers so that employees in our Facilities and Services Department and Physical Plant Departments can self-identify if they are willing to take a temporary leave. Staff who are affected by this decision have already heard from us directly.

Despite the challenges we are facing as the result of the pandemic, we remain committed to our community and charting a path forward. We are doing everything we can to sustain our workforce and adapt as we move through this crisis. We have established an advisory group, focused on plans for the fall, and we will continue to follow advice from public health and government guidelines. The University of Toronto has recently announced a plan to support employees in working from home where possible until at least September. St. Michael’s is part of this collaborative effort to achieve a gradual and safe reopening of the city’s workplaces.

Fortunately, in addition to calling on the expertise of our in-house resources, we can also tap into the knowledge and best practices of organizations such as Universities Canada to help us continue to do what we do best as a centre of learning and faith committed to building the common good.

Our Collegium remains a strong sounding board and a source of advice, responding wisely and compassionately to the unique concerns raised by the pandemic. Last week, the USMC Senate discussed the impact of COVID-19 on our academic community. We head into the coming year in especially capable hands, with former St. Michael’s Principal Dr. Mark McGowan returning as Interim Principal, as Prof. Randy Boyagoda becomes Vice-Dean, Undergraduate in the Faculty of Arts & Science at U of T. As well, Dr. John McLaughlin will again serve as Interim Dean of the Faculty of Theology as Dean James Ginther returns to the classroom following a leave. We are also very fortunate to have continued great student leadership, and I have already begun to work with Cianna Choo and the newly-elected executive of SMCSU.

While there is still so much we do not know about the course of this pandemic, rest assured that we will continue to communicate via email, social media and our website, stmikes.utoronto.ca, with important information about the 2020-2021 academic year and how and when the campus will reopen. Yes, we are in extraordinarily challenging times, but we are truly all in this together, and with your help St. Michael’s serves as an anchor of hope, an engaged and compassionate community dedicated to serving the greater good.

I am proud to be a member of this remarkable community.

Gratefully,

David Sylvester, PhD

President and Vice-Chancellor

University of St. Michael’s College

Although a virtual ceremony took the place of an in-person Convocation at the conclusion of their university experience, members of the Class of 2020 look back fondly on their time at St. Mike’s, starting from the moment they first set foot on campus. “Every time I think about my time at St. Mike’s,” Michael Coleman (Honours Bachelor of Science: Physiology and Biochemistry double-major) says, “it really starts from the welcome I got” during Orientation Week.

Anna Zappone (Honours Bachelor of Arts: Environmental Geography major, Forest Conservation and English minors), a veteran of St. Michael’s orientations over several years, agrees. “It’s such an amazing week, no matter what goes wrong or whatever happens,” she says. “Everyone screams until they lose their voices – everything is just so extreme and it’s just so fun.”

The thrill of the week’s activities introduces new students to a community of care and support. Coleman remembers Orientation for the way “it makes you feel a part of something bigger, but not intimidating,” a quality he did his best to communicate to new students when serving as an orientation leader and residence don in later years. “Everyone’s your family,” he says. “It’s gotten better every year.”

Brennan Hall provides a setting for Paul Nunez’s (Bachelor of Arts: English major, Classical Civilization and Anthropology minors) memories of St. Michael’s. “I really love how’s there’s a community within the Coop,” he says, “very outgoing, encouraging strangers to join in the fun.” Though he often spent late nights there hitting the books alongside his classmates, “we don’t usually talk about what we’re studying.” The camaraderie grew irrespective of programs or disciplines.

Joseph Rossi (Honours Bachelor of Arts: International Relations major, History and Political Science minors) remembers this feeling of camaraderie in Brennan, and across campus generally at “move-in days, Dean’s cup events, and great conversations in the residence or in the Coop.”

“The college system is great at UofT, and I think it’s an important experience,” Rossi says. While students benefit from the larger University of Toronto setting, St. Michael’s provides community and support on a smaller scale, something that students often mention as being uniquely valuable. “I think that St. Mike’s is where I found my support network,” says Michelle De Pol (Honours Bachelor of Science: Neuroscience specialist, Physiology minor). “I will remember the support that I felt from other students at St. Mike’s most.”

Julia Orsini (Honours Bachelor of Arts: Political Science major, English and Italian Culture and Communication minors) comes from a long line of St. Michael’s grads, setting her memories of community on campus alongside those of her family. “It’s true what they say, St. Mike’s is a very tight knit community,” she says, mentioning the Office of the Registrar and Student Services as giving her essential support throughout her undergraduate experience. “They were really there to listen and hear what was going on, not only in my academics but in life,” she says. “They want to see you succeed.”

Family is, of course, the word that keeps coming up in reference to the St. Michael’s community—and that family only continues to grow. “I met my best friends here,” Kate Friesen (Honours Bachelor of Science: Immunology major, Physiology and Biology minors) says. “Living in residence, we would go out—like half the floor would come to McDonald’s to get a coffee at 1 a.m. to keep studying.”

Echoing several of her classmates, Friesen says the most memorable thing for her about St. Michael’s is “how welcoming everyone was, and how supportive the whole community was, and how fantastic the people were.”

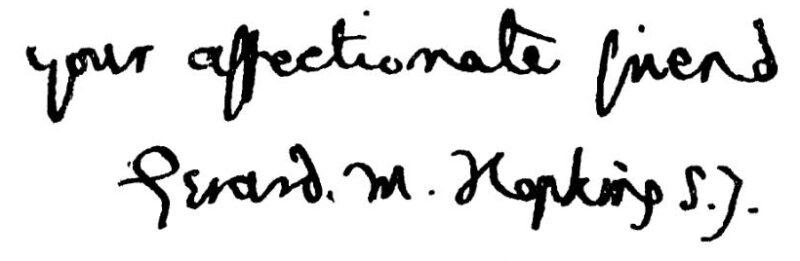

Dr. Stephen Tardif is an Assistant Professor in the Christianity and Culture Program at the University of St. Michael’s College. He also offers courses in the Book and Media Studies Program. This spring, Dr. Tardif was named as co-editor of The Hopkins Quarterly, an international journal of critical, scholarly, and appreciative responses to the life and work of Gerard M. Hopkins, S.J., as well as to those of his circle.

Reading Hopkins in Quarantine

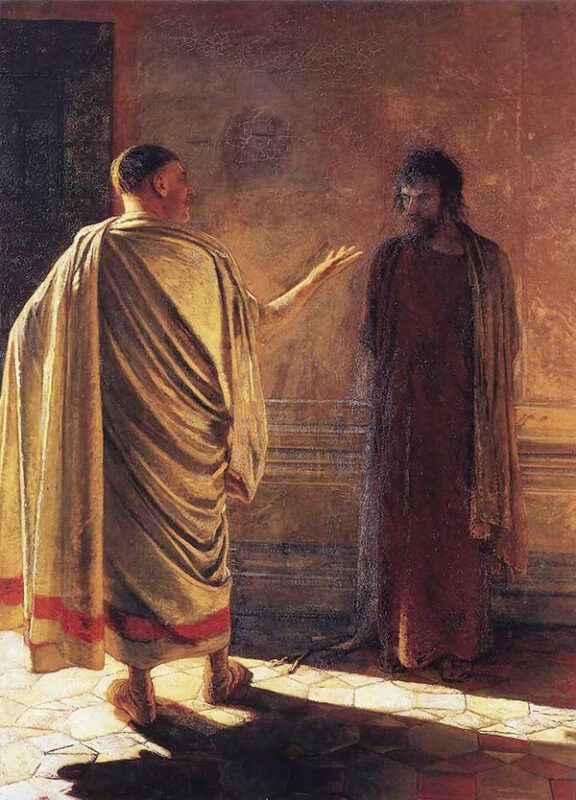

By April, the poet was already sick; in June—just six weeks shy of his forty-fifth birthday—he would succumb to an infection for which, within a decade, there would be a widespread, life-saving vaccine. The death of the Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, from typhoid fever in 1889 appears to present a number of grim contrasts: a young man cut down in the prime of life, who dies from a soon-to-be cured disease. And yet, as his illness worsened, Hopkins’ mood seemed to lighten: the last letters to his family offer consolation, his reported last words, “I am so happy,” offer inspiration.[1] And his last poem, which he sent in April to his best friend, Robert Bridges, offers an “explanation”—this, indeed, is the poem’s last word. Although typhoid is certainly very different from the pandemic we face today, we can take a lesson from Hopkins about how to endure both the disease itself and the disruption it continues to cause, especially from his final poetic achievement.

This poem, a sonnet entitled, “To R.B.,” is, in fact, addressed to his best friend, and it ended what Bridges later recalled being “a sort of quarrel” between them, one precipitated by a joke and some hurt feelings.[2] Hopkins had teased Bridges about the small run of a forthcoming collection of his poems; Bridges parried with a reminder that Hopkins had published virtually nothing at all; with the peacemaking poem that Hopkins sent his friend, he provides a kind of alibi for his silence. Hopkins, who had only sporadic poetic inspiration for years, turns this privation into an invitation to imagine the very impulse that he lacks. The result is one of the most successful examples—and accounts of—poetic creation in the English language.

Hopkins’ poem is thus a reminder of the abilities that we possess, even in times of quarantine, confinement, and infirmity. While we might not all have be able to describe the artist’s creative act, we do have the power to maintain and renew the social bonds between us. While the sonorous, Latinate rhyme-words which end the poem —“inspiration,” “creation,” and “explanation” (ll. 10, 12, 14)—might seem to rise with the first two words but fall with the last, this word is really its pinnacle. After all, this explanatory poem, which reconciled friends who would soon be separated by death, precipitated the experience of inspiration that it captures so well. Above even the poetic muse, then, Hopkins elevates our power to write letters, make phone calls, and send emails to the family and friends from whom we have been separated—or estranged.

But there is another lesson to take from “To R.B.” In a winning, lyric passage from her first novel, Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson describes a counterintuitive relationship between presence and absence:

For when does a berry break upon the tongue as sweetly as when one longs to taste it…and when do our senses know anything so utterly as when we lack it? For to wish for a hand on one’s hair is all but to feel it. So whatever we may lose, very craving gives it back to us again. And here again is a foreshadowing—the world will be made whole.[3]

Hopkins, too, turns his lack of inspiration into the subject of his poetry; the absence of that affect becomes the thing which he describes in verse. The poem confirms the otherwise paradoxical insight of the French philosopher and mystic, Simone Weil: “Every separation is a link.”[4]