For the students in Dr. Paolo Granata’s Media Ethics class at the University of St. Michael’s College, the theoretical suddenly — and urgently — became reality with the introduction of the COVID-19 social distancing guidelines.

“We were just discussing digital inclusion when self-isolation guidelines arose and students suddenly had a real-life experience of seeing how important digital inclusion really is,” explains Dr. Granata.

Digital inclusion, and its companion term, digital inequality, refer to the importance of fair access to both the tools and the data needed to participate in the digital world. In 2011, the United Nations’ Human Rights Council declared the Internet to be integral to human rights, and recommended that Internet access should be a priority for all.

The effects of the current pandemic bear this out, Dr. Granata says, with people needing access to the Internet not only to telecommute and take e-classes but also to do things like pay bills, order groceries and stay in touch with others to reduce isolation.

“Nobody should be left behind,” the professor says.

But everything from income levels to location can have an impact on how people are able to connect. Low-income families, for example, may not have a computer at home for children to do e-learning from home while people living outside of urban centres may have limited access to high-speed Internet, if they have access at all. In turn, working and learning from home can result in soaring data charges.

The closure of institutions due to coronavirus limits access to tools like loaner laptops from schools or banks of computers at libraries, Dr. Granata notes, while shuttered coffee shops and institutional sites means fewer Wi-fi hotspots, where users can find access without having to pay.

Even for those with technology at home, the various platforms now being called on for online learning and e-meetings requires updated software, and that can sideline even those with relatively new computers.

This new reality prompted Dr. Granata to work with his Media Ethics students, research assistants Simon Digby and Alexandra Katz, and the Media Ethics Lab at the University of Toronto to create a call to action on the topic of digital inequality. Titled #DigitalCloseness, the statement spells out how the private sector, various civic organizations, and private citizens all have a role to play both today as well as in the long term to ensure Internet access is available to all.

#DigitalCloseness suggests telecom companies, for example, forgive late payments and keep customers connected at this time, while it suggests community organizations and not-for-profit groups can offer access to free courses and virtual tours of exhibits.

In turn, private citizens with unlimited data are urged to share with a neighbour, to lend an extra device to someone who has no access, or to begin to build a virtual community to check in on others.

Going forward, Dr. Granata says, the conversation must continue with a variety of stakeholders to ensure there are ethical standards in the digital world to protect and further the common good.

There are conversations to be had, for example, in the subject of media literacy so that people do not fall prey to false or misleading information on social media, he says.

“We also need to urge legacy media to choose their words carefully for example, so that they avoid sensationalism by falling back on terms like ‘the battle’ or ‘the war’ on coronavirus,” he says.

Conversations about connectivity must also be mindful of who the most vulnerable are in our communities and work to include them.

For the students of the Winter 2020 session of Media Ethics, COVID-19 taught an invaluable lesson, Dr. Granata says.

“People often think that online and real life are two different things. They’re not, and this crisis has demonstrated it,” says, adding that it’s time for the broader population to become familiar with a term coined by Oxford Professor Luciano Floridi: “onlife.”

With the city as its classroom, a new Media Ethics Lab at the University of St. Michael’s College will help students respond to the ethical issues being raised by rapidly emerging technologies and new communications practices.

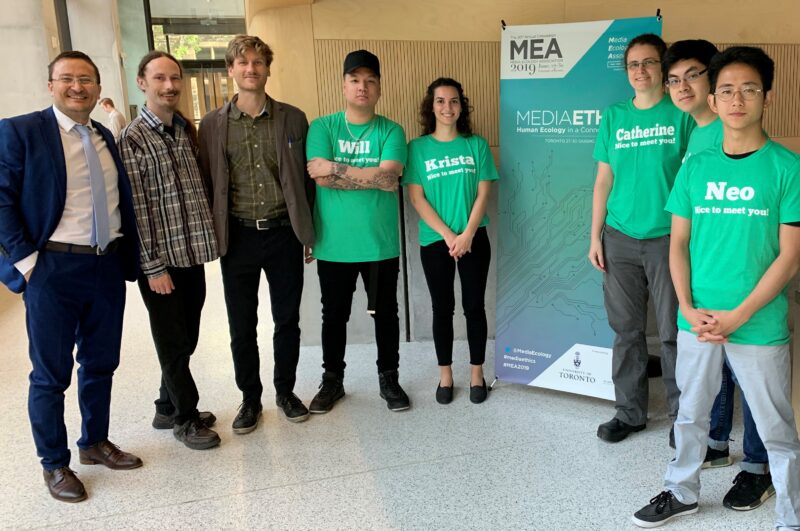

The project is spearheaded by Dr. Paolo Granata, an assistant professor in St. Michael’s Book and Media Studies program. The lab springs naturally from an international conference Dr. Granata chaired earlier this year on the University of Toronto campus in his capacity as the vice-president of the Media Ecology Association (MEA). The conference, Media Ethics: Human Ecology in a Connected World, had a goal of exploring new ethical perspectives and frameworks to help build a digital ecosystem that will serve society in healthy and productive ways.

Popularized by Neil Postman, the phrase media ecology is based on the work of Marshall McLuhan. For those unfamiliar with the term, the MEA’s website defines it as “the idea that technology and techniques, modes of information and codes of communication play a leading role in human affairs.”

The Media Ethics Lab, explains Dr. Granata, is built upon open research, allowing a diverse, collaborative body of stakeholders, from students to media activists and organizations, to freely share information on academic programs and research initiatives to foster ethical thinking in research, learning, and civic engagement.

He views the virtual Media Ethics Lab as both an intellectual and social space where interested parties can gather to study and discuss the ways in which digital culture impacts today’s society. He sees it as a sort of clearinghouse to help society stay ahead of the curve of emerging technologies and the ethical issues that can come with them.

For now, the lab will focus on three core areas: Digital Equity, or creating equitable, inclusive communities for all; the Digital City, focussed on designing people-centered information systems; and Digital Literacy, looking at helping communities develop skills to carry them forward into the 21st century.

“Private companies rule our digital world,” says Dr. Granata. “If public policy is too slow, then the market will come first,” regardless of the impact new technologies have on ethical issues relating to matters such as privacy or artificial intelligence.

“The Media Ethics Lab is being started not only as a research project but also as an opportunity for experiential learning,” he adds, noting that some of the lab’s funding comes from the Advancing Teaching & Learning in Arts and Science (ATLAS) program at the University of Toronto.

And this is where the “city as classroom” idea, another McLuhan concept, will come into play. Experiential learning, explains Dr. Granata, means stepping outside of the confines of the university and into the community.

“Everything we do must be able to support, foster and advance and open an inclusive society, as we must not only work towards a healthier digital world, but a more equitable planet” and that requires students getting involved in civic engagement to listening to what a broad range of people think.

He cites as an example a recent workshop students participated in at Mozilla Foundation in Toronto, a global non-profit dedicated to keeping the Internet a global public resource that is open and accessible to all. Students were invited to provide suggestions and proposals, an empowering experience that allowed them to test-drive their ideas, giving the theoretical a practical turn.

Another form of engagement via the Media Ethics Lab will be periodic charrette sessions, a type of intensive brainstorming meetings where various stakeholders gather for respectful discussion identifying both the benefits and challenges of the current digital media landscape, all with an eye to making improvements.

“We want to foster and support positive change. All of the Media Ethics Lab’s efforts are also are done in support of the UN’s sustainable development goals.” Dr. Granata says.

Several students have already been involved, either in the conference end of this project, or now by on establishing the lab, including Kelsey Mcgillis, Alexandra Katz, and David Lee, all Book & Media Studies students at St. Mike’s as well as Robert Bertuzzi, PhD candidate at Western University, and Simon Digby, recently graduated at British Columbia’s Quest University.

Going forward, the lab will provide both training and mentorship to the students, encouraging them to participate in academic discussion and debate, necessary skills to carry forward if they are to help shape future policy or plan to teach.

Training and mentoring will be provided by Dr. Granata as amplification of his Media Ethics course. Some Book & Media students will serve as research assistants, conducting background reading in the field and participating in periodic discussions to come up with research questions and creating dossiers on their findings.

Working with Dr. Granata, they will post to the www.mediaethics.ca site, selecting both scholarly and non-scholarly publications, as well as a range of commentary to further the discussion. Students will engage in discovering funding opportunities and learn to draft grant proposals.

“The information environment is very much like the natural environment, and we need to take care of the information environment in much the same way we tend to ecological consciousness ,” says Dr. Granata. “The Internet is polluted but it should be a place where people can go and grow. Discussions on media ethics can help restore health.”

That care will require new thinking on how to stop corporate behaviour that is detrimental to society, he adds. Fines in response to privacy breaches, for example, simply don’t work because they aren’t large enough and, more importantly, don’t change behaviour, he says.

“To move forward, we need a humanistic approach to redefine the interface of humans and technology. It’s time to apply ethical thinking in the process of designing new technology.”

The Media Ethics Lab is a step in the right direction.