In 1852 Armand Comte de Charbonnel, Toronto’s second bishop, took stock of the needs of his community. Though around 5,900 of the city’s 23,500 residents identified as Catholic at the middle of the 19th century, there existed no opportunities for university-level theological training from a distinctly Catholic perspective. Understanding the lack—and the opportunity—Charbonnel wrote to the Congregation of St. Basil in Annonay, France, to request that the Basilian Fathers develop and care for an educational institution in Toronto.

Father Jean-Mathieu Soulerin, CSB, arrived in Toronto with three of his confrères later that year to begin the work of the new institution. Under the auspices of St. Mary’s Lesser Seminary and St. Michael’s College, classes were offered in the fall of 1852, and in 1853 the two institutions were merged into St. Michael’s College. Father Soulerin presided as the College’s first Superior, and the Basilian Fathers directed studies.

In its early period, St. Michael’s College gave instruction at the high school, college and seminary levels. Training young men for the priesthood was a priority for the young institution. With the donation of four lots of his estate to the school, John Elmsley provided St. Michael’s with land directly adjacent to the University of Toronto, and a new campus and church were opened there in the late 1850s.

With a rigorous and classical program of instruction, St. Michael’s grew through the late 19th century and became affiliated with the University of Toronto in 1881. The two schools continued to develop in tandem until St. Michael’s became an official Federated College in the University in December of 1910. The first St. Michael’s student to graduate from the U of T did so in 1909, and an inaugural class of six students donned caps and gowns in May of 1911.

A robust catalogue of courses in Catholic philosophy gave students of this era the ability to study for degrees at the University of Toronto while taking some of their most foundational classes from St. Michael’s faculty members. In the early to mid-20th century, the school played an essential role in the renewal of Catholic thought that began in 1879 with Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris, which encouraged Catholics around the world to return to the study of Aquinas and scholastic philosophy.

Etienne Gilson, Bertram Windle, and Jacques Maritain were scholars and writers of global reputation who established themselves at St. Michael’s College during this period. Gilson and Maritain are still remembered as presiding spirits of 20th century Thomism. Pope Pius XI’s papal charter establishing the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies in 1939 accelerated St. Michael’s along a track towards preeminence in the Catholic philosophical world.

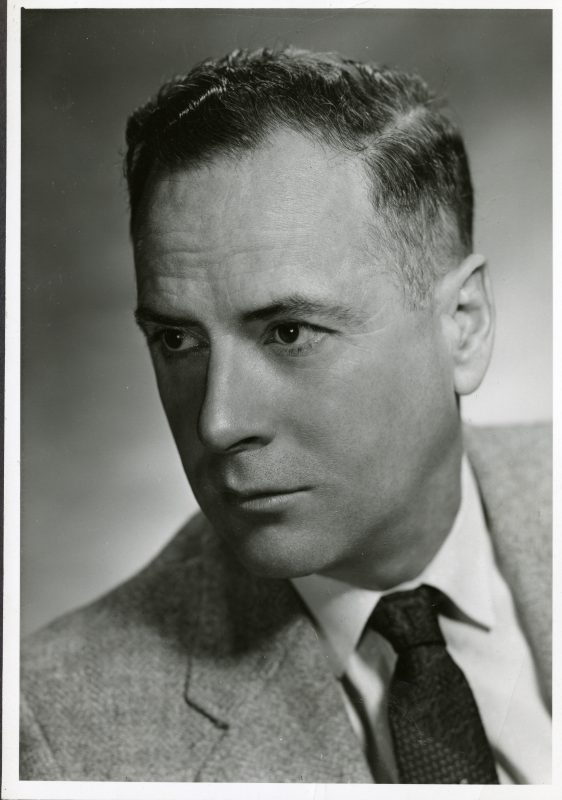

The school still relied upon the instruction of the Basilian fathers during this period, but one of the first faculty appointments of a Catholic layperson in 1946 proved decisive in cementing the reputation of St. Michael’s. When Marshall McLuhan first moved in with his family to an old coach house on Elmsley Place, no one on campus could have known that a global celebrity was about to take the stage.

Old and new: while Gilson and McLuhan were colleagues, their students could study medieval thought and cutting-edge media theory during the same term. The unifying theme between these apparently disparate offerings was the deeply curious, reflective and creative Catholicism that the great scholars shared.

The Memorandum of Understanding (1974) and Memorandum of Agreement (1984) between the University of Toronto and its federated colleges absorbed the St. Michael’s faculty into the umbrella Arts and Sciences faculty at the University. The memoranda dramatically changed the relationship between St. Michael’s and the University of Toronto in terms of undergraduate teaching. The former college departments of English, French, German, Classics, Philosophy, and Religion, maintained their physical presence on the St. Mike’s campus but were now incorporated into larger departments of the same name within the Faculty of Arts and Science at the University of Toronto. Federated Colleges (St. Mike’s, Trinity, & Victoria) were permitted to offer distinctive interdisciplinary programs for the benefit of the entire undergraduate body. St. Michael’s drew from its rich academic traditions and created programs in Celtic Studies, Mediaeval Studies, and Christianity and Culture. In 2003, drawing from the legacy of McLuhan, the College created the Book and Media Studies Program.

The renovations to undergraduate teaching also included a new management structure at St. Michael’s. In 1976, President John M Kelly, divested the running of the undergraduate division to the newly created Office of the Principal. Professor Lawrence Lynch of the Department of Philosophy was the first to hold this office. The Principal would report directly to the Dean of Arts & Science for the development of courses in existing programs and the creation of new programs and undergraduate initiatives. Lynch and his successor principals would also be responsible for the hiring of new faculty who would eventually replace many of the members of religious orders who were now retiring. By 2012, there were no members of the founding religious orders teaching undergraduates at the College.

With a slate of SMC One programs, First-Year Foundations courses, and exciting new faculty appointments, St. Michael’s continues to pursue a unique vocation in the world of Canadian higher education.

Though the Basilians have given up their academic posts to lay successors and the majority of students no longer matriculate in the course of preparing for priestly vocations, Bishop Charbonnel’s response to the needs of his Toronto community in 1852 continues to bear fruit—and the harvest is not only for Ontario, but for the world.