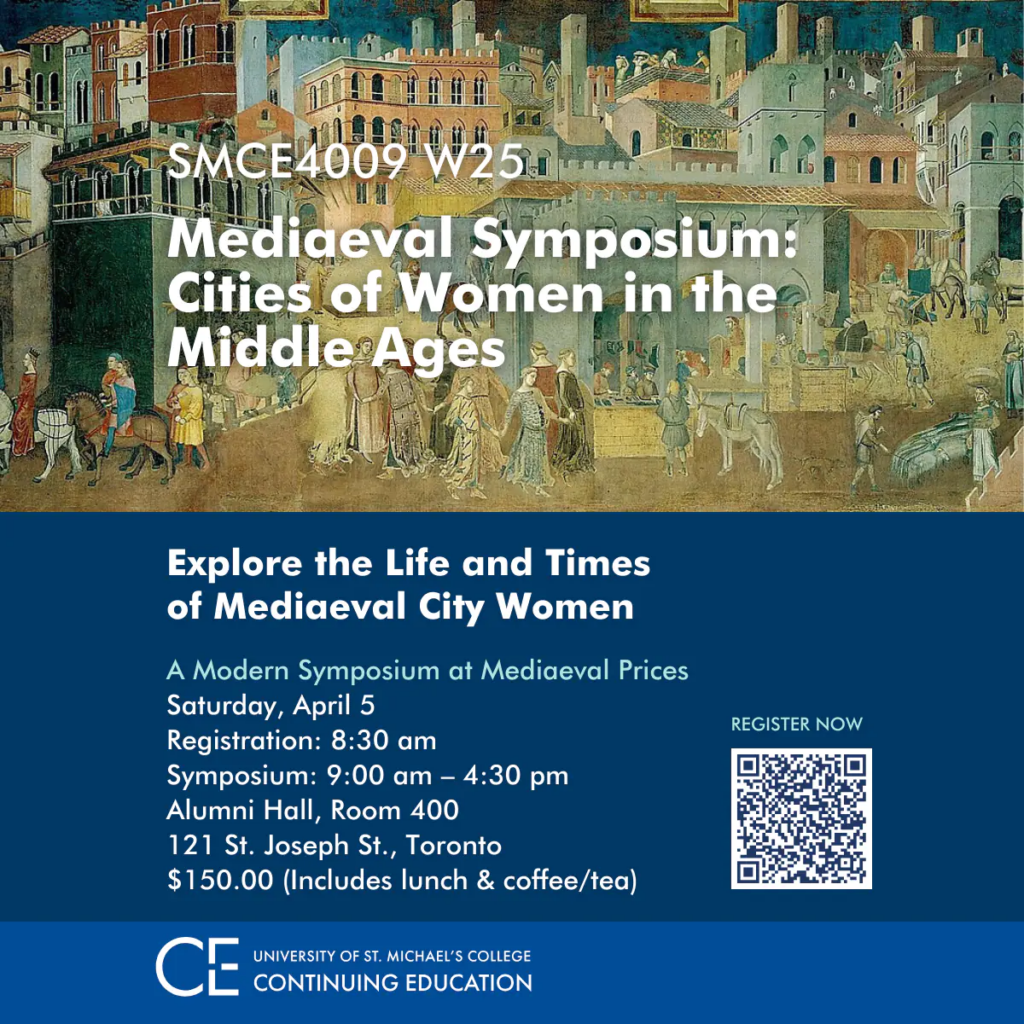

St. Michael’s Continuing Education Division offers a range of courses with instructors who are leading lights in their fields. This conversation with Professor Jacqueline Murray, who is hosting the April 5 symposium, “Cities and Women in the Middle Ages,” launches a discussion series to introduce the people behind our exciting slate of offerings.

Q: Let’s begin with two-pronged question: How do you explain the continuing fascination with the Middle Ages and, in particular, with women in the Middle Ages?

A: Somehow, there is the belief that the Middle Ages is irrelevant to our modern society, but people forget that these are our foundations. The Catholic Church is but the most obvious example, but it is not just an institution. It was mediaeval church thinkers who laid the ethical foundations that permeate western society: ideas such as just price or the need to provide evidence to convict a person in a court, rather than relying on hearsay or public opinion. Our parliament is a mediaeval institution that continues to govern a free and democratic society. It is only now that technology is challenging the predominance of that very important mediaeval invention, the codex, the book, which transformed learning and education because books are both easy to use and easy to search and contextualize the information they contain (ideas can be seen to follow a logical order). E-books and databases decontextualize knowledge (what went before? What comes after?) and are, in my view, more difficult to search. One typo and you are told nothing exists!

If we move from mediaeval culture to mediaeval women, we also encounter misapprehensions: that all women were oppressed or forced to marry. That they gave birth constantly until they died in childbirth. Women were either sitting in a field, covered in mud, as per Monty Python and the Holy Grail, or were grand ladies with servants and great wealth and even some power, as per Eleanor of Aquitaine in The Lion in Winter. Neither perspective reveals the complexities of gender nor the opportunities women found even within a fundamentally patriarchal society. Nuns lived lives relatively unimpeded, with opportunities for education. Women in cities and the countryside were essential contributors to the household enterprise. Men and women, husbands and wives both contributed to the household economy, as did children as soon as they were able. For example, artisan and merchant class women were usually literate, managed the shop and apprentices and did the accounts. Rural women managed the household garden and animals, selling milk, eggs and produce at the local market. And the whole family worked in the fields at different points in the growing cycle. It is these women who tend not to be visible to modern eyes.

Q: Please explain the intriguing title of the day “Cities of Women in the Middle Ages”.

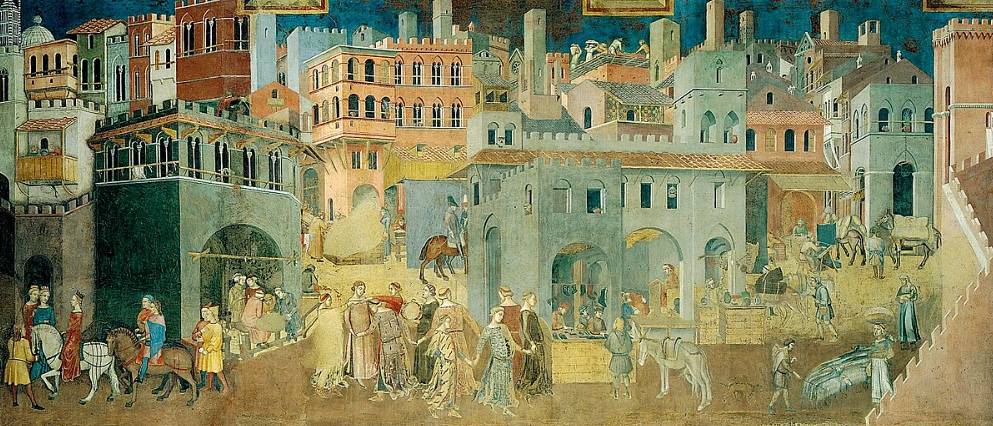

A: The title invokes the famous book by mediaeval writer Christine de Pizan who, after she was widowed, supported herself and her family as a professional. She wrote two significant books that informed the title of the symposium: The City of Ladies and The Book of Three Virtues. The first book collected the stories of virtuous women from the past, in order to counteract much of the prevailing misogynist literature being written by men of the time. The second is a conduct book. Many such books were written for rulers – kings, queens, princes, and so on – but Christine’s book encompassed women from queens to country dwellers and even prostitutes, discussing how they could fulfill the expectations of their rank. So, with these inspirations, the theme took shape as focussing on women, real women rather than ideal tropes, who lived in different cities and lived different kinds of lives. The symposium, then, is a kind of sampler of women’s lives, from different countries, different economic and social ranks, different religious communities who were all part of the surge in urban life that characterized the later Middle Ages.

Q: Obviously there are very practical differences between life then and now but how do women’s lives compare now to then? What is some of the common ground and what are some of the key differences?

A: Cities, then and now, were home to women of disparate backgrounds and professions. They often attract young women to move from smaller, often rural, communities to find the greater opportunities promised by urban life. Cities offered women economic opportunities, the chance to meet new people or to find a husband. Cities also had jobs for women so they could save money for marriage or to simply to find autonomy. This sounds very much like the attractions of city life today.

Q: Please walk us through the day’s schedule, elaborating on how you chose your panel and what you hope attendees will take away from the sessions.

A: My goal was to find the very best scholars working on the most interesting topics; people who could really bring mediaeval urban women to life, across geographic breadth, since different areas of Europe presented women with different life situations. So, we will be fortunate to hear about women in the big cities like Paris and London, leading ordinary or extraordinary lives. And working and merchant women from lesser-known cities in Scotland and Spain, as well from an Italian provincial town. Within that quest for breadth, we will also have depth by looking at specific groups of women in their specific urban contexts. This brings me back to the sampler image again, a sampling of women from a sampling of cities discussed by an exquisite sampling of mediaevalists. I really think this will be an amazing opportunity for the audience – women and men both – to be introduced and given an overview of the late Middle Ages.

There will be three speakers in the morning and two in the afternoon. The morning has a focus on working women in cities that cross from Scotland to Spain, and include merchant women, nursing sisters, and Jewish traders. In the afternoon, we will see women who were engaged in literary debates and another whose story is linked to one of the most famous of mediaeval writers, Chaucer.

There will be coffee breaks along with a mediaeval lunch – the kind of fare found at a mediaeval table, to provide the chance for informal discussion about things mediaeval.

This symposium is intended to leave attendees with a feeling of satisfaction in learning about a new area of history, as well as sparking a desire to find out more. I recommend to those who are left curious or hungry for more Middle Ages, to pick up a copy of The Bright Ages, A New History of Medieval Europe by Matthew Gabriele and David Perry (2021) a brilliant overview of a bright period of history.

Q: One of the sessions talk about women’s poetic expression. What can we learn from that? And what of the lives of Constanca and Cecily, whose names appear in session titles? What do they tell us?

A: Constanca and Cecily represent a larger group of women who were in many ways similar to Christine de Pizan. While they did not have to write to earn money, they were not just literate women, of whom there were many, but also literary women, who could challenge the literary eloquence of the male writers of the day.

Q: How did your own interest in the medieval world begin?

A:In high school I had been interested in history, but at university I floated a bit like so many students today, not knowing what exactly to focus on (and having escaped the current pressure into STEM against both my nature and inclination). Then, by serendipity, I heard a guest lecture about libraries in the Middle Ages, by a wonderful and engaging mediaevalist, and that was it. I was hooked and never looked back. I took everything mediaeval, including Dante, early Christianity, and Latin language, along with kings and popes and then, what became the focus of my graduate studies, marriage and family. With each stage, I kept moving closer and closer to the real people of the Middle Ages, and that is my hope for this symposium, to bring us closer to the real women and the men with whom they shared life in mediaeval cities.

Q: What can the Middle Ages teach us about modern life?

A: It can help us to understand how we reached where we are now. It can provide examples, or perhaps similes, on contemporary situations, such as the current political and economic turmoil, and its results. It can reflect that societies are more complex and richer and varied than they might first seem. And the Middle Ages provide a long view of history as change over time. Mediaevalists deal in centuries rather than decades or even years. Events that seem important or even devastating are also ones that change and evolve. Placing oneself in the broader flow of history helps to put the present into context and allows us to hope for the future.

To learn more about Mediaeval Symposium: Cities of Women in the Middle Ages or other St. Mike’s Continuing Education offerings click here.