A new course at St. Michael’s will take a deep look at the history and legacy of residential schools in Canada. Christianity, Truth and Reconciliation is offered as a First-Year Foundations Seminar and is open to all first-year students in the Faculty of Arts & Science in the University of Toronto.

A significant portion of the course will be the presentation of parallel histories: invitations to collaboration and mutual listening on the part of Indigenous leaders, and the all too frequent, tragic rejection of these amicable overtures by both church and state officials.

“My hope is that students come out of the course with the clear-eyed understanding of the way that European Christianity collaborated with the Canadian state to implement this program of cultural genocide—a clear-eyed view of the complicity in this project—but also a clear sense of other possibilities of relationship,” says course creator and Associate Professor Dr. Reid Locklin. The latter half of the course will also present ways that Indigenous Christians and Indigenous partners in conversation with Christians seek a creative rethinking of the Christian tradition on Turtle Island, the name many Indigenous communities call North America.

Locklin uses the term “cultural genocide” to describe the “total program” of the Canadian government to “exterminate Indigenous persons as Indigenous persons [and] remake them in the image of white Canadians,” a program in which Canadian churches were complicit. Because St. Michael’s is a Catholic university, the course responds to Calls-to-Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report directed at both churches and educational institutions.

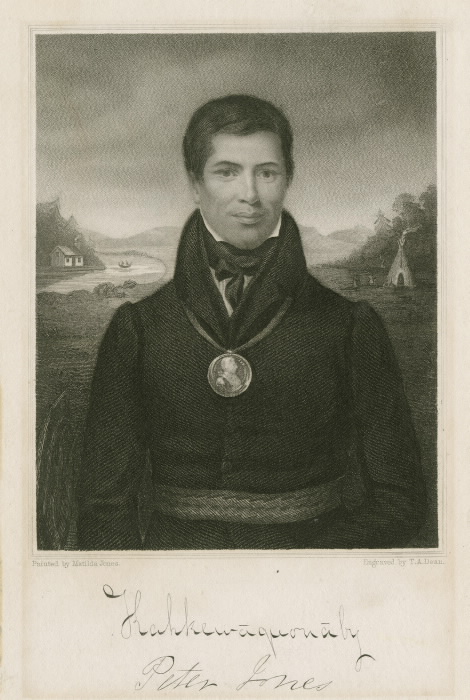

“We think about—one—do we have a place for looking at this history, particularly as a Catholic school, but also—two—how do this history and the rich traditions of knowledge in Indigenous nations and peoples have an impact on how we teach everything?” Locklin says. This second theme of the course opens a “less well told history of creative engagement of Indigenous persons and nations with Christianity,” including Sacred Feathers (Peter Jones), a Methodist minister and leader of the Mississaugas, and Louis Riel, a Catholic Métis who played an important role in the formation of Manitoba and Canadian confederation.

Bringing one of the course’s themes directly into its pedagogy, a key piece of Locklin’s course is a partnership with the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. Located at Algoma University, the centre maintains an archive of records related to residential schools across Canada, including both an Anglican-run residential school that operated on its grounds and a nearby Spanish Catholic residential school. The centre will make these archives available to students for research and exploration.

“The Shingwauk school was used by the state for cultural genocide, but when Anishinaabe leaders originally initiated the school they had a different, creative vision for what that school should be,” Locklin says, and that vision combined their own knowledge traditions with elements of European learning. The state’s dismissal of this opportunity for partnership is one of the “lost opportunities” he wants students to learn about in order to be able to see “the possibility of alternative pasts and alternate futures.”

Shingwauk itself is built on a model of partnerships with the Garden River Reserve and the Anishinaabe Nation, and when the centre was formed it established an advisory committee of residential school survivors. As part of Lockin’s final unit on apologies and reparations, students will have an opportunity to hear from a survivor panel. Locklin hopes that future students will be able to visit Shingwauk as part of the course.

There are lessons about this past available in the very ground on which St. Michael’s campus stands, and the course itself is one part of the University’s larger engagement with the Calls-to-Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Locklin received a grant from Arts & Science to create treatylearning.ca, a website that offers a non-Eurocentric revisionist history of the land.

Uncovering untold stories about the land St. Michael’s operates on is one aspect of a larger effort to accept rather than ignore an invitation to partnership, allowing Indigenous histories and traditions to reframe the University’s story. Other past related initiatives at St. Michael’s have included round table and blanket exercise events at the Faculty of Theology, reading collections in the Kelly Library, and reading groups for staff and faculty on Indigenous histories and issues.

“It is very important that a Catholic University address the Church’s engagement with Indigenous peoples in a meaningful way as a means of uncovering the truth, which is a necessary step to reconciliation,” says St. Michael’s Interim Principal and Vice-President Mark McGowan. “This seminar engages the students with primary sources relating to this Christian-Indigenous encounter and addresses the tough questions that have arisen from this history in Canada. A seminar of this nature is long overdue.”