Fr. Gustave Noel Ineza, OP, is a doctoral student at St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. Born and raised in Rwanda, he lived through the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi and went into exile for a month in what was then Zaire. His family left the refugee camps and returned to Rwanda after three members of his family developed cholera. He studied in the minor seminary and joined the Dominican Order in 2002. He studied Philosophy in Burundi, and Theology in South Africa (SJTI/Pietermaritzburg) and the UK (Blackfriars/Oxford). Ordained in 2014, he worked for Domuni (www.domuni.eu) and was a chaplain to university and high school students. In 2018, he came to Canada to pursue studies in Christian-Muslim dialogue. He is currently reading on post-colonial approaches to the taxonomies assigned to religious traditions (Muslims and Christians) by colonial powers in Rwanda.

Do We Need Someone to Die to Remind Us that Black Lives Matter?

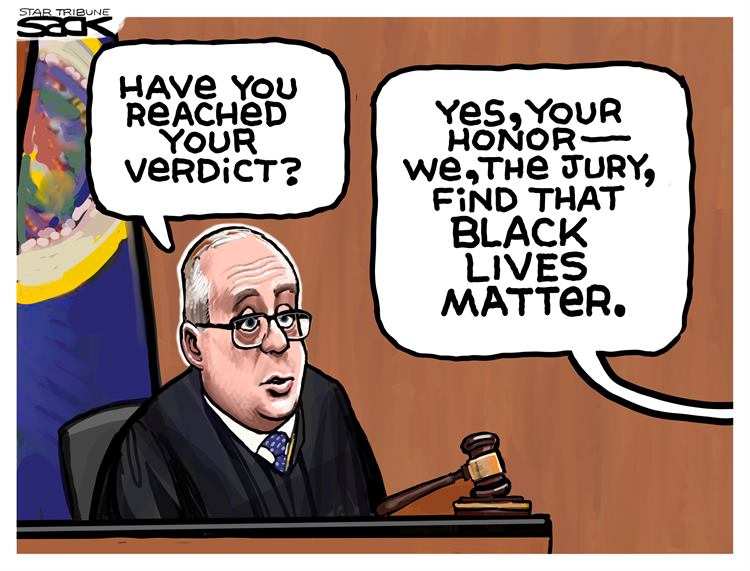

Black lives matter! That was more or less the verdict, 11 months after the brutal killing of George Floyd by Officer Derek Michael Chauvin, and 43-day-long traumatic trial. Twenty-nine years and a month after the trial of four police officers who savagely beat Rodney King, the fear of an acquittal gripped American society used to police officers’ trials ending with disappointing verdicts and acquittals.

The trial finished ahead of the U.S. Senate vote on a bill on April 21, 2021 to combat anti-Asian American hate crimes. Racial tensions have spiked in the United States, tensions that followed the empowerment of white supremacists, a reality which reached a peak with the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, a gathering of racist groups that envied the 1930s Reichsparteitage or Nuremberg Rallies.

Four years prior to George Floyd’s murder, a 24-year old Malian-Frenchman, Adama Traoré, died, on his birthday, in police custody, after he was brutalized by French police. Since Traoré’s death, a huge debate has begun in France. Universalist leftist thinkers were scared that rhetoric that generalizes about police brutality might hinder the “Republic,” a chimeric ideal of French unity that assumes all French citizens are equal and equitably treated by the law. Realist activists, often represented by a courageous woman named Rokhaya Diallo, never stop warning the French that there is a risk of considering the American police brutality as something particular to America, because it is widespread in many European cities. Diallo, who seems to carry alone the Black Lives Matter movement on her shoulders, has become the black sheep of a denialist French media because of her positions. The French President’s attacks on “American” Postcolonial movements, “a catch-all term covering everything from anti-colonial thought to critical race theory, intersectional theory to Black Lives Matter,” highlight the persistent denial of oppression towards racialized minorities in many former colonial European powers. Protests to bring to justice Traoré’s murderers were met with brutal police reactions. France is deeply immersed in denial of its racist colonial past, which lives on in its treatment of racialized minorities.

Indeed, change may take several decades to come, even in the United States. After the verdict was announced, the U.S. Representative for New York’s 14th congressional district, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, wrote on her Facebook page: “That a family had to lose a son, brother, and father; that a teenage girl had to film and post a murder; that millions across the country had to organize and march just for George Floyd to be seen and valued is not justice. And this verdict is not a substitute for policy change.” Former U.S. President Barack Obama wrote that “true justice requires that we come to terms with the fact that Black Americans are treated differently, every day [and] millions of our friends, family, and fellow citizens live in fear that their next encounter with law enforcement could be their last.” Obama added: “While [the] verdict may have been a necessary step on the road to progress, it was far from a sufficient one. We cannot rest. We will need to follow through with the concrete reforms that will reduce and ultimately eliminate racial bias in our criminal justice system. We will need to redouble efforts to expand economic opportunity for those communities that have been too long marginalized.”

Japanese Tennis player Naomi Osaka, who grew up and lives in the U.S., tweeted these very heartbreaking words: “I was going to make a celebratory tweet but then I was hit with sadness because we are celebrating something that is clear as day. The fact that so many injustices occurred to make us hold our breath toward this outcome is really telling.” In other words, no reasonable person believes that the verdict on Chauvin’s crimes signifies the end of police brutality to Black people. It becomes even harder when some influential TV hosts, like Fox News’ Greg Gutfeld, made it clear they believe Chauvin may not be guilty. Gutfeld stated that the only reason he would want the verdict to incriminate Chauvin is because his neighborhood was looted last summer.

The whole idea of looking at Black people as a threat has been used to justify the discriminatory policing of Black neighbourhoods and unreasonable stop-and-frisks of Black people by law enforcement in the U.S. One highlight of the trial occurred when one of the prosecutors, Steven Schleicher, explained the difference between a threat and a risk. That some insecure white law enforcement agents, empowered by systemic racism in their institutions, might be inhabited by an unreasonable fear of black people transforms Black people neither into threats nor risks. That Brooklyn Center Police Officer Kim Potter, while training a rookie, had to pull a gun on Daunte Demetrius Wright for an outstanding driving ticket explains what may go on in the routine training of American police officers. The fact that she screamed “taser, taser, taser” while shooting him with a gun is also confusing. My training officer in my military service forgot to tell me about the usefulness of screaming “gun, gun, gun” while I am shooting at the target! The most surprising thing is the many peaceful arrests of white mass shooting perpetrators, such as Kyle Rittenhouse and Dylann Roof, which proves that police officers are trained in how to de-escalate tensions, even with highly dangerous individuals. Apparently, that training does not equally apply to people of colour.

One of the most racist whataboutisms on police criminal treatment of Black people in the U.S. is the objection phrased in these words: “What about Black-on-Black crime?” Black-on-Black crime is punished, sometimes beyond the realms of reasonable corrections. In almost all instances when police are accused of the summary execution of Black people, judicial institutions focus on police training guidelines. The fact that Black lives matter is not news to Black people. Black people who take other Black peoples’ lives know they committed a crime and that they would be seriously punished if caught.

The verdict in Chauvin’s trial does not end anti-Black racism. Orchestrated attacks on Colin Kaepernick’s knee may have ended but it will still take years before Black people start feeling safe anywhere around the police. I still get followed by the police in some liquor stores. When I am, I still have the luxury to bother them with words like: “Oh! Because you are here, can you help me find a Coudoulet de Beaucastel Côtes du Rhône Blanc and a Philippe Colin Chassagne-Montrachet, please?”—in a very French accent. However, most Black people are extremely bothered by their presence. An African American friend advised me to never ask them to fetch me a lemonade.

I think the Church must be careful in these times. When people marched against police brutality following George Floyd’s killing on June 1st, 2020, President Donald J. Trump ordered the peaceful dispersal of the crowds protesting near the White House so that he might stage a photo-op before St. John’s Episcopal Church. In a brilliant article for The Atlantic, Garrett Epps, Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Baltimore, called it “Trump’s Tiananmen moment.” However, the most alarming aspect is that President Trump chose to violate American citizens’ First Amendment rights so that he could take a picture in front of a church, holding a Bible. The following day, President Trump and first lady Melania Trump visited the Saint John Paul II National Shrine in Washington. While many religious leaders condemned the photo ops, Trump still managed to sow discord among Christians—those who thought his attitude toward protests against police brutality was godly versus those who were disgusted.

Many police departments have Christian chaplains, and law enforcement agents are members of our parishes. Just as Church leaders in the past transformed the pulpit as a place to theologically defend civil rights, it is a Christian duty that it become clear to all the faithful that to God, Black lives matter.

Read other InsightOut posts.