John Sampson is a fourth-year PhD Student at the University of St. Michael’s College in the University of Toronto. He is writing on the life and thought of the Chinese theologian T.C. Chao. John can be found at home most days, writing his thesis and drinking only the finest cups of hand-crafted coffee.

In Search of Christian Unity: A Chinese Christian Perspective

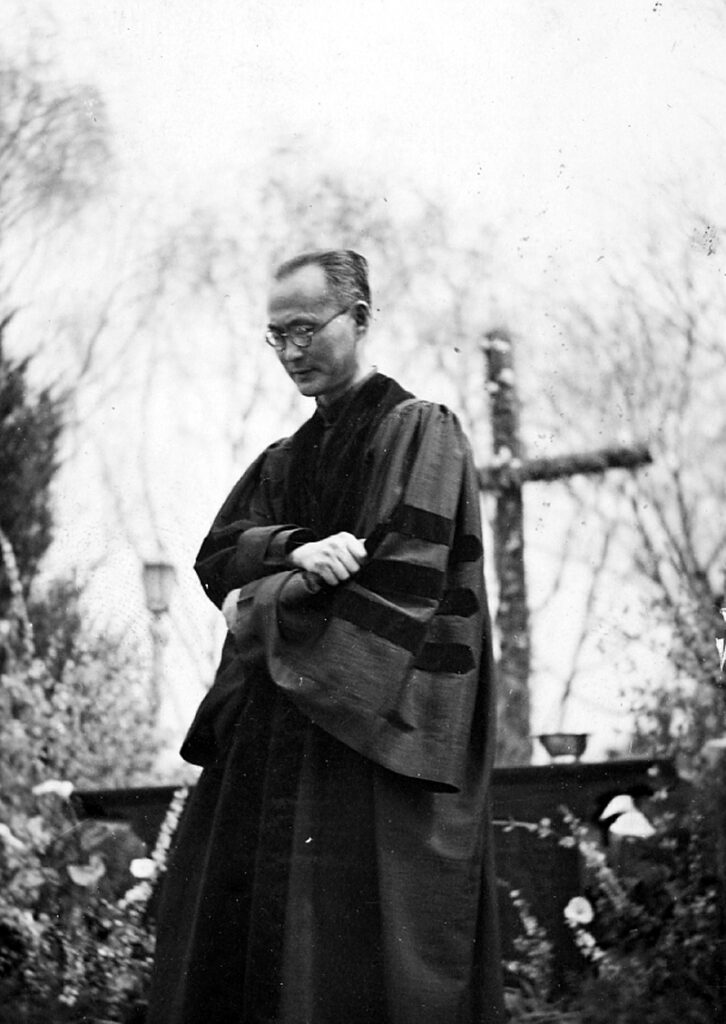

“People must be involved in the work of building up the Church,” wrote T.C. Chao (1888–1979), a famous Chinese Christian theologian and one of the first presidents of the World Council of Churches. “[Christians] do not have the authority to divide arbitrarily, because it is the will of Christ to tear down walls of separation, to split open curtains of division, and create in himself one new person,” he said, alluding to Ephesians 2:14–22. What Chao penned in 1946 has ongoing relevance for Christians around the world today, as we come together during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity and pray that we may be one “so that the world may believe” (John 17:21). T.C. Chao gave expression to a conviction held by many Christians in the Chinese Republican Era (1912–1949), the period of time when Christianity burst on the scene unlike ever before in China. The conviction was that unity and cooperation were essential if Christianity was to survive, if Christianity was to put down roots in China.

A major obstacle to this pursuit of unity, however, came from the fact that North American and European Christians were trenchantly divided, importing this division into China. Throughout the nineteenth century, foreign mission societies refused to work alongside one another. Catholic and Protestant missionaries remained fixated on their own approaches to Christian faith, on their own doctrinal precepts and ecclesiastical teachings. Protestant denominations produced competing Bible translations and promoted their own translation efforts over and against any other. With few exceptions, Western Christians let divisions that brewed in Europe spill into China, and nurtured these divisions without supplying adequate means for letting a Chinese expression of Christianity take root. This was a deep-seated problem. The desire to preserve Christian practices from one culture (i.e. Europe) stifled the voices of Christians from another culture (China). It stifled the possibility to be enriched by what Chinese Christians themselves had to offer.

In the 20th century things began to change. Many Chinese Protestants criticized the denominational conflict of the Western Church and sought to overcome disunity through the formation of the National Christian Council in 1922. The following year, the Roman Catholic Church convened the first council of the Catholic Church in China, and later consecrated six Chinese bishops in 1926 to allow for greater control over territorial jurisdiction. These practical ways of ensuring that Chinese Christians chart the course for Chinese Christianity were followed by attempts to root Christian identity in a shared Chinese cultural heritage. Just as European Christians turned to Greek philosophers like Aristotle to help advance theological reflection in Middle Ages, Chinese Christians turned to figures like Confucius and Lao Tzu to help shape a unified vision for doing theology in China. The truth of God manifested in classical Chinese learning, argued L.C. Wu 吳雷川 (1870–1944), could be fulfilled in Jesus Christ, who was God’s Way (or Dao 道) made flesh. Just as the moon reflects the light of the sun, so could sages like Confucius reflect the light of Jesus Christ, said Y.J. Zhang 張亦鏡 (1871–1931). Christians could, and indeed, must be sincere about promoting Chinese culture, argued the polymath Roman Catholic theologian P. Joseph Zi 徐宗泽 (1886–1947), who followed the example of the pioneering Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610). For the first time in history, Chinese Christians shed light on ways of being Christian that were in touch with their own culture. Christian thought and practice were being rooted not in European Christian thought-forms, but in Chinese ones. And unity among Christians of different theological persuasions was beginning to take hold.

But, sadly, throughout the 20th century, crisis and conflict continued to mount in China and sap the strength of a unified Christian effort. The Communist Revolution (1949) collapsed any and all such efforts. The newly established People’s Republic of China restructured all religious practice through official, state-sanctioned Churches, causing the activities of both Catholic and Protestant Christians to become a heavily monitored affair. In our day, with the unprecedented rise of underground house churches and unregistered Christian gatherings, Chinese Christianity has shown that it is not going away any time soon. But Christians now remain painfully divided. As with the Christian division that erupted in St. Cyprian’s day from the Decian persecutions (250 AD), Chinese Christians are divided between those who have joined official, state-sanctioned Churches and those who have refused and faced persecution as a result.

As we think about and pray for Christian unity, we remember that it is not always an easy thing to put into practice, and can indeed cost a great deal. It cannot be imposed, but most flow naturally from the lived-practices of Christians themselves who come from the diverse cultures of the world. Conscious of the things that divided Christians in his day, T.C. Chao saw discord and division in a certain light, in light of the suffering Saviour himself. The divided and broken body of Christ, the Church, sees itself as thus filling up or completing “what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions,” Chao said, citing Colossians 1:24. Christian division is that state of suffering which the Church enters into and remains in until it attains the resurrection. The Church’s bitter hardship amidst discord and brokenness is the way of the cross, a way it can embrace but which, in the end, it hopes to surmount in union with the one, resurrected Christ. This was T.C. Chao’s vision, one which has ongoing relevance for us today as we think about and pray for Christian unity.

Read other InsightOut posts.