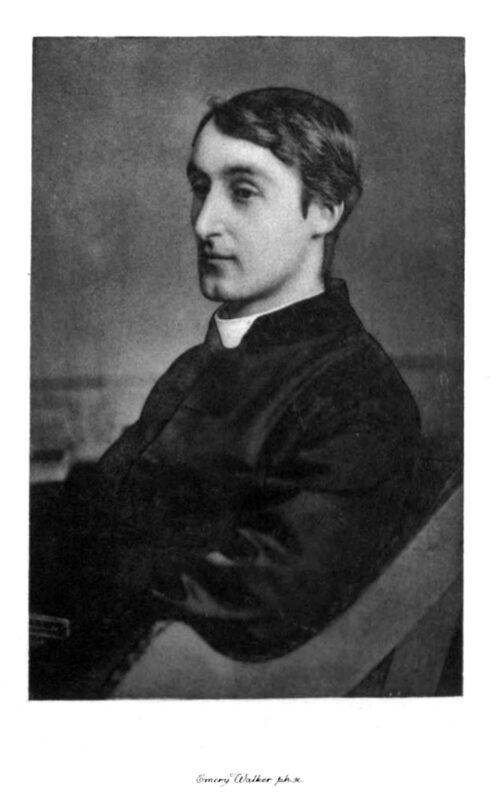

Dr. Stephen Tardif is an Assistant Professor in the Christianity and Culture Program at the University of St. Michael’s College. He also offers courses in the Book and Media Studies Program. This spring, Dr. Tardif was named as co-editor of The Hopkins Quarterly, an international journal of critical, scholarly, and appreciative responses to the life and work of Gerard M. Hopkins, S.J., as well as to those of his circle.

Reading Hopkins in Quarantine

By April, the poet was already sick; in June—just six weeks shy of his forty-fifth birthday—he would succumb to an infection for which, within a decade, there would be a widespread, life-saving vaccine. The death of the Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, from typhoid fever in 1889 appears to present a number of grim contrasts: a young man cut down in the prime of life, who dies from a soon-to-be cured disease. And yet, as his illness worsened, Hopkins’ mood seemed to lighten: the last letters to his family offer consolation, his reported last words, “I am so happy,” offer inspiration.[1] And his last poem, which he sent in April to his best friend, Robert Bridges, offers an “explanation”—this, indeed, is the poem’s last word. Although typhoid is certainly very different from the pandemic we face today, we can take a lesson from Hopkins about how to endure both the disease itself and the disruption it continues to cause, especially from his final poetic achievement.

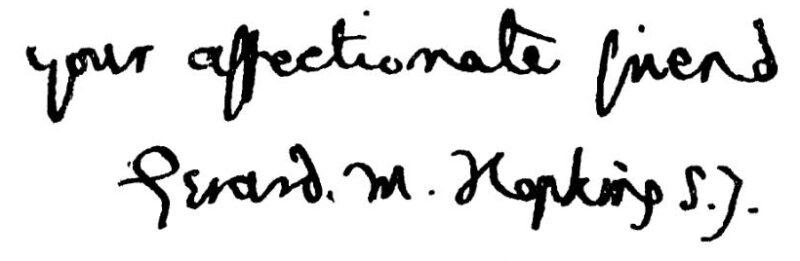

This poem, a sonnet entitled, “To R.B.,” is, in fact, addressed to his best friend, and it ended what Bridges later recalled being “a sort of quarrel” between them, one precipitated by a joke and some hurt feelings.[2] Hopkins had teased Bridges about the small run of a forthcoming collection of his poems; Bridges parried with a reminder that Hopkins had published virtually nothing at all; with the peacemaking poem that Hopkins sent his friend, he provides a kind of alibi for his silence. Hopkins, who had only sporadic poetic inspiration for years, turns this privation into an invitation to imagine the very impulse that he lacks. The result is one of the most successful examples—and accounts of—poetic creation in the English language.

Hopkins’ poem is thus a reminder of the abilities that we possess, even in times of quarantine, confinement, and infirmity. While we might not all have be able to describe the artist’s creative act, we do have the power to maintain and renew the social bonds between us. While the sonorous, Latinate rhyme-words which end the poem —“inspiration,” “creation,” and “explanation” (ll. 10, 12, 14)—might seem to rise with the first two words but fall with the last, this word is really its pinnacle. After all, this explanatory poem, which reconciled friends who would soon be separated by death, precipitated the experience of inspiration that it captures so well. Above even the poetic muse, then, Hopkins elevates our power to write letters, make phone calls, and send emails to the family and friends from whom we have been separated—or estranged.

But there is another lesson to take from “To R.B.” In a winning, lyric passage from her first novel, Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson describes a counterintuitive relationship between presence and absence:

For when does a berry break upon the tongue as sweetly as when one longs to taste it…and when do our senses know anything so utterly as when we lack it? For to wish for a hand on one’s hair is all but to feel it. So whatever we may lose, very craving gives it back to us again. And here again is a foreshadowing—the world will be made whole.[3]

Hopkins, too, turns his lack of inspiration into the subject of his poetry; the absence of that affect becomes the thing which he describes in verse. The poem confirms the otherwise paradoxical insight of the French philosopher and mystic, Simone Weil: “Every separation is a link.”[4]

Sooner or later, the restrictions and precautions which have been adopted during this pandemic will fade, and we will no longer measure the minima of social distances or the concavity of curves. But our appreciation for the things and the people that we miss—those that will be restored and those that won’t—need not wait on any government policy or public health finding. As Robinson reminds us, “the world will be made whole.” Until then, in the “winter world, that scarcely breathes that bliss,” (l. 13) we can yield explanations to each other and embrace the strange gift of separation which is already a foretaste of that ultimate completion.

[1] See Paul Mariani, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Life (New York: Viking, 2008), 425.

[2] Mariani, 418.

[3] Housekeeping (New York: Bantam Books, 1982), 152-153.

[4] Gravity and Grace, trans. Arthur Wills (Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1952), 200.

Read other InsightOut posts.