Martyn Jones is a content specialist in St. Mike’s Office of Communications. On a freelance basis, he also writes reported features, essays, and criticism for online and print outlets. He and his wife’s toddler Fox has just turned two years old.

Reading Out Loud or, The Whale

When Herman Melville died in September of 1891, his novels were out of print. He had by then spent several decades writing poetry no one seemed to enjoy, least of all his long-suffering wife. The success and fame he earned early in life writing semi-autobiographical novels about seafaring—those stores had all been depleted long ago. His obituary in the Times even misspelled the title of his greatest book, still decades from being recognized for what it was.

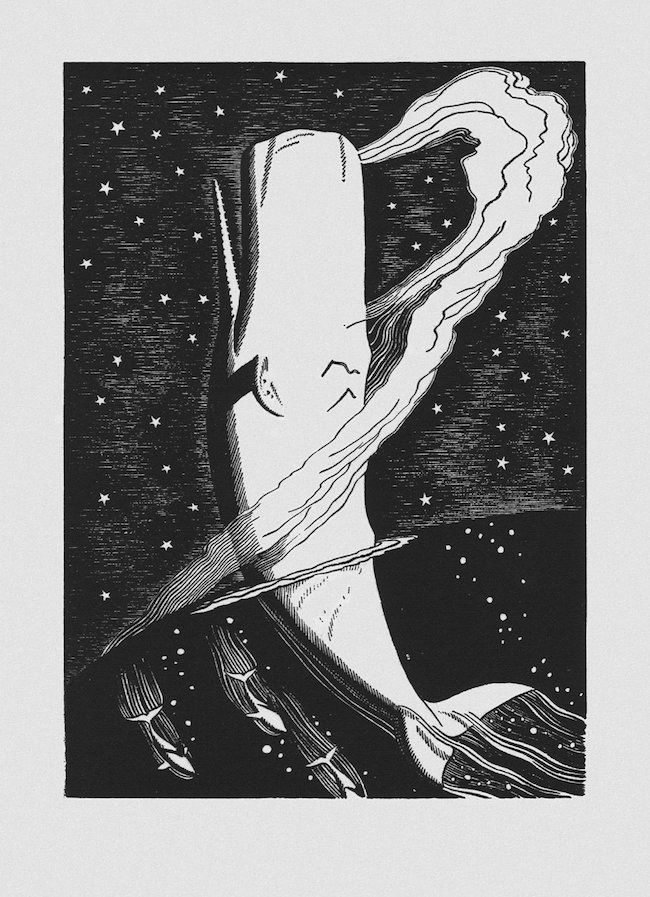

1851 is the year Melville published Moby-Dick or, the Whale. It is the story of Ishmael, a man who, to rid himself of his depression and see the world, joins the crew of a Nantucket whaling ship called the Pequod. Captain Ahab presides over the vessel, emerging from his cabin to clomp across the deck with one leg made of whalebone. In a violent encounter with an albino sperm whale on an earlier voyage, Ahab was “dismasted,” and after recovering from the loss of his leg he developed a diabolical obsession with the perpetrator. His mission of revenge against the whale will, in the end, cost the lives of every man aboard the ship but one.

While this summary makes Moby-Dick sound like one more adventure story written from Melville’s experiences as a young sailor, the book departed from its predecessors in containing a huge amount of musing about—well, everything: life, the universe, the whaling industry, fate, democracy, table manners, civilization, the taxonomy of whales, and the human situation in the midst of it all.

Moby-Dick was first reviewed in England by critics whose three-volume copies were both censored in various places and misprinted to exclude the epilogue. The latter would have been a minor error had that last page not explained how Ishmael, the book’s narrator, survived the cataclysmic wreck of the Pequod at the climax of the book. Imagining their simple-minded American cousins capable of accidentally writing a story narrated by someone who does not survive the events being narrated, the critics attacked Melville, and American reviewers, cowed by their sophisticated English peers, adopted their posture. Moby-Dick sold poorly, as would everything else Melville wrote from then on.

Moby-Dick has a claim to being the great American novel; if it isn’t that, it may at least be the greatest American novel so far. Ahab’s vengefulness against an animal foe develops a superlatively powerful expression of the theme of humanity’s struggle with nature. Vivid metaphors in every chapter suggest meanings beneath meanings and other meanings under those, giving the story a feeling of infinite depth. The many voices and registers, the occasional stage directions, the scenes of comedy, the stately rhythm, and the exclamation points—he uses them unsparingly!—all make the book an absolute blast to read out loud.

This is just what my wife and I have been doing to conclude the day. After our toddler is asleep, our chores are done, and we’ve closed the laptop after a last episode of whatever show, I bring out my heavy and heavily dog-eared paperback copy of Moby-Dick and start to read. We’re over a quarter of the way through, having just witnessed Ahab’s dark speech to the crew about their voyage’s singular objective, and the toast the crew makes to the death of the whale.

Melville’s complex and semicolon-laden sentences sometimes flow too hard to shape them with the right intonation or verbal emphasis, but this is all part of the fun—as is sounding out unfamiliar words, or laughing in spite of yourself. (The Pequod’s third mate, Flask, is unable to help himself to butter while dining with the captain for reasons of psychology and decorum, which Melville explains at length before saying, “however it was, Flask, alas! was a butterless man!” I laugh every time I read this passage and still couldn’t tell you why.)

Shakespeare’s plays—themselves meant to be spoken and heard rather than read—were Melville’s literary obsession before composing Moby-Dick, and their rhythms provide the book with its line-level tempo. There are whole passages that would scan as perfect blank verse with the addition of a handful of line breaks. Like a steam engine, the rhythm of iambic pentameter creates momentum, and when you start to hear that rhythm and match it with your own voice, it can carry you away.

It’s easy to get carried away, of course: to use silly voices, to read too loudly or forcefully, or even for your voice to crack or give out. In my experience, this adds to the enjoyment for the reader and the listener. When you give voice to someone else’s words, you put your own stamp on them, and through the processes of your memory, they leave an imprint on you as well. The quiet chuckles and pauses to sort out some obscure meaning add something to the experience of the book: a quality of communal enjoyment.

Melville’s spotty career and tumultuous personal history are relevant, too: as they created the conditions that gave rise to his great book, so might there be a kind of perfection in the awkward or unsteady voice of a parent, partner or friend reading Moby-Dick out loud, especially if they’re reading through the imperfect medium of a video call. Even in this scenario, far from ideal, reading aloud transforms art into shared experience. When stuck at home—or “whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul,” as Ishmael says—there are few things as needful as that.

Read other InsightOut posts.