Nisheeta Menon is a graduate of St. Michael’s Christianity & Culture program and holds a Master of Divinity degree from the Faculty of Theology. While studying theology she served as the Social Justice Co-ordinator and Student Life Committee Vice-President. She is now a high school Religion teacher in Mississauga, where she hopes to continue her co-curricular work serving her school community in the areas of equity and diversity education and chaplaincy.

Wandering in the Desert

Autumn is a time of year I have always loved. As a student, I looked forward to transitioning back into school and the start-up of all of the clubs, sports, and activities. Now, as a secondary school teacher, my appreciation of this time of year has only increased. It is around this time that the life of a school starts to take shape—student leadership, chaplaincy, athletic teams, volunteer and outreach initiatives, arts programs, etc. Plans turn into reality and the school begins buzzing with activity, creativity, and life!

This autumn, as you might imagine, looks very different. The beginning of the school year was tumultuous, to say the least, and some of us only received our teaching assignments in late September. A number of teachers, like me, were designated to teach the online cohort and, with that, we have sunk into the routines of virtual teaching with considerable reluctance.

Students continue to be moved in and out of our courses due to a host of scheduling issues while the quadmester is rapidly progressing toward its end date in the second week of November. The tight timeline forces teachers to compress the curriculum, either speeding through important concepts or eliminating them entirely. The students “attend” class daily but are behind their screens while we are behind ours, and, even when our cameras are on, there is a palpable discomfort.

In a regular classroom, these students would know each other quite well by Grade 12, and they would continue to build connections with one another throughout their time in a class like mine. In the virtual environment, however, students in my classes are from all over the school board and, despite my efforts, their interaction is limited. As well, during the average school day, my colleagues generally remain isolated in their own classrooms (for good reason), leaving the staff lounge and department offices empty. The school is eerily quiet and the few faces you may pass are hidden behind masks. This is a far cry from the Thanksgiving liturgies, staff potlucks, and Student Council Haunted House tours of the past.

For most teachers, even those with in-class cohorts, the laments are the same: feeling disconnected from the students, being unable to teach and assess in an effective way, concern over students with access issues or learning challenges, and a general lack of guidance and support. At the same time, we watch the news as reports of COVID-19 cases in schools rise and we check in with some of our close friends and family as they await the results of their tests. We miss the loved ones who are outside of our social bubbles, and we worry about them, and ourselves. It is difficult to be hopeful.

One day, as I discussed these grim realities with a colleague, I confessed I was having a difficult time staying optimistic and energized, but that I was simultaneously feeling guilty about this because I also acknowledge how privileged I am in many ways. She offered one of the most helpful comments I have heard throughout this pandemic: “Of course you’re having trouble staying hopeful! What do you expect? We are the Israelites in the desert! This is not the Promised Land!”

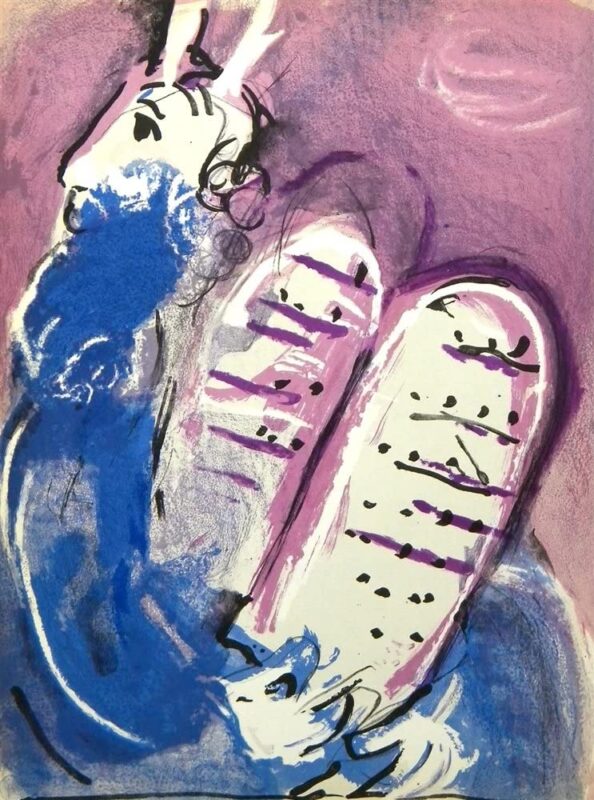

Coincidentally, it was at that very time that I was in the midst of discussing the Exodus story with my Grade 12 Religion class. We had talked about how the Israelites in the desert must have felt a sense of hopelessness, fatigue, monotony, and an underlying fear that they might never actually reach the Promised Land. It is difficult to imagine that they ever woke up optimistic and chipper, ready to spend another day wandering in the desert!

During this pandemic, part of the struggle which so many of us put ourselves through is trying to make our lives as close to what they were pre-pandemic as possible. Of course, this is nearly impossible, and our failure to meet our self-imposed standards only heightens our anxiety. By acknowledging that we are “in the desert,” perhaps we can give ourselves permission to feel a little lost, at times hopeless, and generally unable to think more than a few steps ahead at any given time.

My most gratifying class thus far occurred when I shelved the curriculum for one day and chatted with the students about how I was feeling. As a teacher, and one of the only adult influences outside of their home they have regular access to right now, I know that modelling for my students the fact that it is okay to be struggling is perhaps the most important lesson that I can offer. After sharing with them a little about what was weighing on me, my students quickly piped in with words of validation and encouragement, which led to other students sharing their particular burdens, which in turn led to more encouragement from the group. Despite the distance between us and the glitchy internet connection, our discussion rolled on until the end of the period. There was laughter, exclamations of, “Oh my gosh! Me too!” and quiet, muffled sniffles at times. We never got around to our lesson on the Book of Exodus that day, and yet I am certain that we came to a better understanding of how the Israelites were able to survive—and find deep meaning in—their time in the desert together.

Read other InsightOut posts.