“Pietism?” “Devotionalism?” Maybe even “escapism?” People learning about the distinctive approach of Eastern Christians to academic theology, might easily presume that their stress on corporate prayer is just one of these “isms.” For more than thirty years, the Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies, now at the University of St. Michael’s College, has issued a schedule of daily worship that accompanies the Institute’s class schedule every semester. The liturgies take

place in the basement of Elmsley Hall in a space refurbished for Byzantine Rite services. Moreover, Windle House, the new home of the Sheptytsky Institute, also houses a small oratory on the second floor that is used for smaller group prayer. On some days, up to three services can be taking place in these rooms – all celebrated by Eastern Christian communities associated with, or invited by, the Institute. The key thing to note is that these are not seminary services. The worshipers are rarely future ordinands.

Why this emphasis on worship as part of an academic theology program, nay general university program? The reasons are actually very modern – in fact, post-modern – which is why the suggestion of “devotionalism” etc. is ironic. Among the great insights of the social sciences as regards education, is that learning is enhanced when it is holistic. People – not brains – learn. Or maybe put better: while the cerebral is crucial for some forms of knowledge, wisdom as well as many intellectual reflexes and sensibilities are best acquired when the whole person in engaged.

Apply this to theology. What happens to our knowledge about the divine, when knowledge of the divine wanes? Moreover, where is knowledge of the divine acquired? Certainly, ministry to the “least of the brethren” and dynamic human relationships, not to mention study and personal prayer, are crucial for the acquisition of such knowledge. However, corporate prayer, according to a canonical liturgical tradition, holds a special place. Worship provides a particular form of “tacit knowledge.” The latter notion, developed by contemporary thinkers like Michael Polanyi, refers to a form of pre-reflexive apprehension that serves to filter reflexive, or analytical cogitation. In other words, it’s a “matrix” that helps a person determine what is believable. Even the most logical and reasonable ideas will not be countenanced if one’s tacit knowledge blocks them.

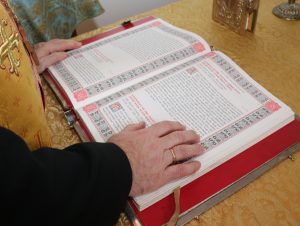

Belief and faith are the air that theology breathes. That “air” circulates and is purified far better when it is not filtered out by a negative tacit knowledge grounded in suspicion, resentment and alienation. Trust, forgiveness and integration are central to dynamic theologizing, and these are uniquely acquired when day after day we allow ourselves to bodily experience the One who covenants, the One who forgives unconditionally, and the One who heals all disintegration (we Byzantines speak of phtharsis – corruption). Liturgical services provide an opportunity for students to bathe in sung doctrine, allowing the Church’s teaching to permeate the subconscious. And the ritual enactment of reconciliation, joy, and sacrifice enable these core experiences to become the stuff of second order reflection. Oh, and did I mention reverence? God’s Word, a key focus of any solid theology is venerated before it is dissected. Doing all of this in community, on a daily basis, helps theologians avoid sidelining such spiritual exercises as they understandably fret about footnotes and philosophies.

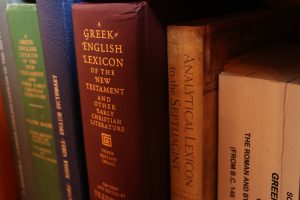

In sum, what transpires in chapel is “theologia prima”; while what occurs in the classroom is “theological secunda.” The former is the pre-reflexive experience of knowing – yet without the ability to critically articulate what is known. The latter is the discursive, conscious, analytical knowing that theology departments foster. In our day, the two categories have been elaborated by the late Yale liturgist Aidan Kavanagh and his University of Notre Dame disciple, David Fagerberg. It is probably no accident that Kavanagh worshiped in the Melkite Rite, and Fagerberg remains the best Eastern Orthodox liturgical theologian alive today, even though he is Roman Catholic.

We Eastern Catholics (e.g. Ukrainian Greco-Catholics, Melkites, Maronites, Chaldeans etc) were called upon by Vatican II to develop our own theologies. Before the Council, we were only allowed distinctive rituals and canonical legislation. The University of St. Michael’s College stands out as the first major university in North America to welcome an institute committed to helping Eastern Catholics fulfill the mandate of Vatican II.

Eastern Catholics have been weak indeed when it comes to theologia secunda. Wars, famines, brain drains, discrimination etc in the ancestral homelands have impeded the growth of the latter. But how we Eastern Catholics dream of the intellectual dynamism – and ecclesial renewal – that will ensue when “prima” and “secunda” become “una.”

This is a transcript of a reflection delivered in the Sheptytsky Institute Chapel before the Collegium Annual General Meeting on Oct 20, 2017. Fr. Peter Galadza, PhD, is the Director of the Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies, University of St. Michael’s College in the University of Toronto.