Father Andrew Summerson has been appointed a full-time, tenure stream member of Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology, where he will serve as an Assistant Professor of Greek Patristics. Prior to the appointment he had held a Contractually Limited Term Appointment with the Faculty for three years.

“I am happy to continue my work with the Faculty, the Sheptytsky Institute, and the University of St Michael’s College to deepen pathways of collaboration on campus with colleagues and the wider constituencies around campus,” he says.

Summerson holds an S.Th.D. in Patristic Theology from the Pontifical Patristic Institute Augustinianum in Rome. His book, Divine Scripture and Human Emotion in Maximus the Confessor: Exegesis of the Human Heart, was published by Brill.

“Professor Summerson brings many talents to this new position, from his wide-ranging scholarship in Patristics and the Eastern Churches to being a great community builder and fostering international networks of collaboration and research,” says RSM Dean Jaroslav Skira. “All of this will continue to raise the profile of an invaluable part of our Faculty of Theology, namely, the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian studies.”

Summerson will continue to teach History of Christianity 1 as well as the courses in Patristics and Eastern Christian Theology.

“The University of St. Michael’s College boasts a proud history of historical studies while engaging the contemporary world,” says Summerson. “I see my own work with Sheptytsky aligned with St. Michael’s heritage: engaging the touchstones of the Eastern Christian past for the life of the world we live in today.”

He looks forward to continuing his work with theology students,

“Early Christian texts aren’t meant to be sipped like wine; they must be chugged like beer,” he says. “I like to read primary sources with my students and treat them not like delicate artifacts, but living voices that speak true statements about God and the Church today.”

For two religious sisters, discovering how to link their concern for the environment with their religious calling meant returning to the classroom. Inspired by Laudato Si’, the encyclical on the care for the environment promulgated by Pope Francis in 2015, Sister MaryAnne Francalanza, FCJ and Sister Benedicta Lim, OSB arrived in Toronto from England and Korea respectively in September 2023 as eco-missionaries for their religious communities. Studying at the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology, (RSM) and particularly within its Elliott Allen Institute for Theology and Ecology (EAITE), has given them a community, hope, and the tools to champion change that they will take back home.

“Science gives us the facts and can help with finding technological solutions, but what needs to be done in order to live in harmony with the Earth and all God’s creatures is change hearts, and that’s in the realm of faith,” says Sister MaryAnne, who had spent 17 years teaching math at a secondary school in Liverpool, England.

She is here for one-year post graduate diploma at the EAITE. As a Faithful Companion of Jesus, she left her teaching position in 2022 to complete her tertianship, a year away from active ministry to deepen her understanding of the FCJ life and charism. In addition to her teaching, Sister MaryAnne describes herself as an “eco-warrior” in her school. She was known to take simple actions like encouraging the students not to waste resources; working with a team of senior students to campaign for meat-free Mondays in the school canteen; and including care for the Earth in prayers and the liturgy. During her year of reflection, she realized she was being called to pursue this passion more purposefully.

The release of Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ in 2015 compelled the Congregation to make care for our planet one of its priorities at its 2019 General Chapter. This year of study supports that priority.

She has enjoyed being able to take courses at RSM, as well as at Trinity College and Emmanuel College, which are also members of the Toronto School of Theology, a consortium of seven theological schools, affiliated with the University of Toronto.

“There’s a cross pollination with people of other denominations, and even of other faiths. In these classes, whenever ecology, climate change or creation is brought up, students want to talk about it and they all bring different lenses to the material,” she says.

When Sister MaryAnne returns to England in the fall, she will be taking back knowledge, ideas, and experiences that she hopes to share in parishes and schools. “I want to build on the good work that other people have already done,” she says.

Sister Benedicta is a member of the Olivetan Benedictine Sisters of Busan in South Korea. Her Congregation joined the Laudato Si’ seven-year action plan and that was the occasion for the Council to send someone to study eco-theology. Sister Benedicta’s Mother Superior requested that she study eco-theology specifically at RSM because the program is internationally recognized and known to the community, as two priests they know had returned after earning their doctorate degrees from RSM.

The Olivetan Benedictine Sisters of Busan are called to do whatever work is needed by the Church and this charism includes working directly with the Earth, so some of their ministries involve farming. Through her studies, Sister Benedicta has come to realize that her community demonstrates concern for the environment through all its ministries, and especially its work with the marginalized. As she gains an eco-theological perspective, she realizes how eco-issues disproportionately affect the poor and disadvantaged.

“Pope Francis sees the poor usually as having the cry of nature. When nature is harmed, people, usually the marginalized, are also being hurt and that’s what eco-theology uncovers. I hope to have their voices be heard,” says Sister Benedicta.

Prior to coming to Toronto, Sister Benedicta had been involved in her community’s parish ministry. She is now in her first year of a Master of Theological Studies degree at RSM, while also earning a certificate in theology and ecology from the EAITE.

While it may have been her community that sent her to study, she wants to apply what she is learning to her life of service. “Ecological theology is not something to study and be done with. It’s something that I must carry until the end in my life,” she says. She thinks her education will give her the confidence to speak up more about environmental issues and have a bigger impact on decision making.

“It has absolutely been wonderful to have Sr. Benedicta and Sr. MaryAnne as part of our community. They have brought their unique interest in eco-spirituality and have enriched our conversations on eco-theology with their passion for and commitment to eco-justice,” says EAITE director Prof. Hilda Koster.

The EAITE oversees a certificate and diploma in ecological theology at RSM. Founded in 1991, it is one of the oldest institutes to offer ecological theology programs, and the only Catholic institute in North America to do so.

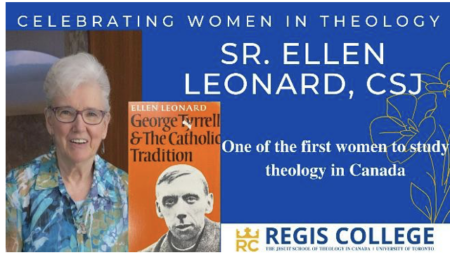

On March 8, the world celebrates International Women’s Day. This year’s theme is “Inspire Inclusion.” Regis St. Michael’s female faculty members are contributing to this by hosting a luncheon on Friday for RSM female studies. In recognition of intersectionality and that female students tend to be the minority in theological studies, especially in the Advanced Degree level, Friday’s gathering hopes to help foster a sense of belonging and empowerment.

Regis College is working to “Inspire Inclusion” through raising the profile of RSM’s female

faculty members and other female theologians from historically marginalized groups, such as M. Shawn Copeland and Cristina Lledo-Gomez.

Each of these distinguished scholars are publicly recognized on our welcome slides at the South

Atrium Doors (facing Wellesley), and throughout the month, we will be sharing these slides on social media and thanking each individual for their contribution to theology. Among those recognized are Margaret Brennan, the first female theology professor at Regis College, and Ellen Leonard, one of the first women to study theology in Canada and to teach at the University of St. Michael’s College Faculty of Theology.

We are committed to inspiring and practicing inclusion. Let us journey in the synodal way with women of all walks of life and work towards a just society.

The University of St. Michael’s College community is remembering Fr. William Irwin CSB as a gifted professor, an inspiring homilist, and a man of extraordinary pastoral skills who cared deeply for his students.

Fr. Irwin, who died on Dec. 6 at the age of 91, was a biblical scholar who specialized in in the Book of Isaiah and the Book of Psalms. He taught at St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology for decades, serving as Dean of the Faculty from 1981-1985. From 2001-2004 he was President of Assumption University in Windsor, On.

Born in Houston, Texas, Fr. Irwin earned a BA and an MA from the University of Toronto and a Baccalaureate in Sacred Theology from St. Michael’s before going on to further studies at the Angelicum and the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome. Ordained a priest in 1959, he joined the Faculty in 1965 and continued teaching part-time into his 80s, well past his formal retirement date.

“Fr. Irwin is one more example of the tremendous debt St. Michael’s owes to the Basilian Fathers,” said Prof. Jaroslav Skira, Dean of the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. “I am particularly grateful for his dedication as Dean of the Faculty of Theology, for his scholarship in the Hebrew Scriptures, and for helping educate numerous graduates–some of whom we count as members of the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology.”

In an address to the Faculty of Theology convocation in 1985, Fr. Irwin spoke to those assembled about the importance of balancing study with lived experience, noting that “the Gospel not only enlightens but transforms,” and urging all to become engaged with the world, using their gifts to teach a message of hope. It is a model his former students recall well.

Doctoral candidate Sr. Carla Thomas O.P. who studied the Psalms with Fr. Irwin, remembers him as “a kind and gentle instructor. Fr. Bill taught by his personal presence as much as by his lecture,” she said. “I was struck that in his retirement years he still continued to teach students, in spite of all the demands that it must necessarily have made on him in so many ways. I remember him telling us that his favorite psalm was Psalm 73, and that God does not punish. Rather, God leaves people to their own counsel.”

Long-time Faculty Professor John L. McLaughlin also studied under Fr. Irwin.

“Bill Irwin was my Doktorvater, directing my Ph.D. dissertation, later was my colleague, and in both roles I considered him my friend,” recalled McLaughlin. “Bill combined insightful biblical scholarship with a deep pastoral sensitivity, both inside the classroom and outside. He was one of the best, if not the best, homilist I have ever heard from a number of religious traditions. In his teaching he combined careful detailed scholarly treatment of biblical texts with the relevance of the results for the Church and the world.”

But, adds McLaughlin, Fr. Irwin “was also attentive to what students were going through. Partway through an individual Reading and Research course in the first year of my doctoral studies, I lamented that I was feeling run down, not sleeping and feeling overwhelmed, ending with ‘I don’t think I can handle a Ph.D.’ He responded that most students felt that way in the first year, then told me not to read anything new for our next meeting, just review what I had read, and told me to take at least one day and sleep. When I walked into his office two weeks later, before I could say anything he asked, “Did you sleep?” He truly cared as much for the person as he did for the project.”

In 2015, Fr. Irwin delivered the Meagher Lecture at St. Michael’s, offering a talk entitled Between Church and Theology: The St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology at 60, to mark the Faculty’s six decades of granting degrees.

He also touched the lives of students he had never taught by endowing scholarships for dozens of students in the Faculty.

Visitation will be held in the chapel of Presentation Manor, 61 Fairfax Cres. in Scarborough, on Friday, December 15 from 9:30 a.m.-10:30 a.m., with a funeral immediately following.

An innovative new course from Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology will see students travel to Rome this summer to focus on a theological and historical overview of the issues that divide Christians, as well as the bonds that unite them.

Catholic Perspectives on the Ecumenical and Interreligious Movements, taught by Dr. Michael Attridge, will be held at Centro Pro Unione, an institution located in central Rome run by the Friars of the Atonement, an order with a charism devoted to actively promoting Christian unity and the founders of what is now known as the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity.

During the course, which runs Mondays to Fridays from June 26 to July 14, students will engage with experts from the Angelicum (the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas) and other Roman universities, as well as from the Vatican’s Dicastery for Inter-Religious Dialogue. Participants will stay at Casa Tra Noi, a hotel close to the Vatican that earmarks its profits for charity, including supporting single mothers, those with dependence issues, and the terminally ill. Costs are generously supported by the Driscoll fund, donor money earmarked for the study of ecumenism.

The course includes lectures, seminars, workshops, and excursions. Along with outings to Santa Maria Maggiore and other sites with a key place in Roman Catholic/Christian life, students will also visit the city’s Jewish ghetto and a mosque, as well as meet with a variety of communities, including a visit to Sant’Egidio, a lay community working with the homeless, migrants, refugees, and people with developmental delays.

One of the highlights of the trip will be attending the Mass of Sts. Peter and Paul, also known as the Pallium Mass, on June 29th. Tradition sees pallia, a vestment article worn only by archbishops and the Pope, conferred on new archbishops on this day, so St. Michael’s students will witness Archbishop Francis Leo, Toronto’s new archbishop and the new Chancellor of the University of St. Michael’s College, receive his pallium, and then have a chance to chat with him.

“As Regis-St. Michael’s works to expand its experiential learning opportunities, this is an exciting chance for our students to learn about the ecumenical and interfaith work of the Catholic Church from those working in and associated with the Vatican’s dicasteries,” says Attridge. “I can’t think of a better venue either: the historic Centro Pro Unione – located in the heart of Rome on one of its most famous squares, the Piazza Navona. The Centro played a key role at the time of Vatican II in hosting weekly gatherings of theologians and ecumenical observers who helped shape the final documents of the Council. In every respect, these three weeks should be an unforgettable experience for our students.”

Along with participation in class and weekly roundtable sessions on the key learning of the week, participants will submit written work and contribute to a blog on the course, Rome 2023, with each student responsible for five posts.

The Catholic Perspectives course is the latest in a long line of experiential courses, classes that involve travel to relevant sites or include hands-on learning. Consider, for example, Prayer and Meditation Through Pencil, Pastel and Ink Sketching, offered at Regis College, which explores the theory and practice of various types of prayer through drawing, or St. Michael’s A Journey Through History – The Jesuit Missions in Early Modern Canada, which is taught at the heart of the former Wendat (Huron) nation (present-day Martyrs’ Shrine.) Another experiential course offered during the summer is Interfaith in the City, which sees students visit various houses of worship to learn more about interfaith dialogue. This course is particularly popular with teachers who are responsible for World Religions course.

While experiential learning courses take place throughout the academic year and are open to all students, the summer courses are particularly helpful to Master of Religious Education students, for whom the condensed scheduling and the inspiration for future lesson planning offer great opportunities and support, says RSM Dean Jaroslav Skira.“Supporting our students is always top of mind for us,” Skira says. “We know people lead busy lives but value a theological education, both personally and professionally. One of our goals, therefore, is to help make our courses accessible to more people while ensuring we are addressing topics that are of interest to our students and serve their personal and professional goals, all while engaging in memorable, inspiring ways.”

To learn more about course offerings – including experiential courses – at Regis St. Michael’s, or to talk about enrolling in one of our programs, please contact erica.figueiredo@utoronto.ca or visit https://theology.stmikes.utoronto.ca/.

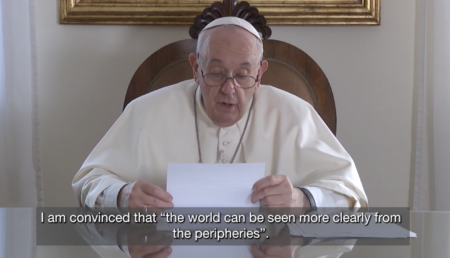

The University of St. Michael’s College will host a key event in Pope Francis’s Synod on Synodality process with the findings from a North American report commissioned by the Vatican as part of the Doing Theology from the Existential Peripheries project to be presented during a panel discussion on campus.

The panel, moderated by Dr. Mark McGowan, will take place Thursday, November 10 from 7-9 p.m. and will also be made available online.

Dr. Darren Dias, OP, an Associate Professor in St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology who also serves as Executive Director of the Toronto School of Theology, was appointed last December by Rome’s Dicastery on Human Integral Development to join the project’s North American working group, with similar exercises conducted around the world. The eight theologians conducting the research listening to the concerns of those on the margins were led by Stan Chu Ilo, a St. Michael’s alumnus who is a professor of World Christianity, Ecclesiology, and African Studies at Chicago’s De Paul University.

“We have presented our findings in the context of a conversation,” says Dias, who explains that there is an ongoing commitment on the part of the working group–and Pope Francis–to listen to the experience of people, and especially to those who often find themselves without a voice. Each of the six working groups around the world is invited to hold some sort of event to share their initial findings as part of an ongoing conversation/listening process to ensure that the findings are known to the general public.

The groups were assigned themes from Pope Francis’s teachings such as migration, ecology, and vulnerability. As the North American report explains, “we take readers into the world of so many people whose voices are not often heard in our churches and society,” with members of the working group visiting prisons, refugee and immigration centres, national borders, convents, holding centres, seniors’ residence, rehabilitation centres, churches and social and pastoral centres, to name a few.

“We are committed to bolstering ways in which theology can support engaging the peripheries,” Dias says. “This is a research project, an academic exercise, and we will report our findings to the bishops, theologians, pastoral workers, and the faithful in service to the Church. This is the business of a Catholic university, to be at the margins. We are committed to bolstering a theology that supports the theological renewal proposed by Pope Francis.”

Pope Francis launched the synodal process in 2021 to help the Church to listen to its constituents and learn from them. The pope has since extended the window during which the synodal process takes place until 2024.

Earlier this year the University of St. Michael’s College Synodal Working Group held seven listening circles for students, staff, and faculty, and conducted 25 one-one-one interviews before submitting a report to Rome on the findings. University President David Sylvester presented a brief summary on the methods used at St. Michael’s to Nathalie Becquart, XMCJ, undersecretary and consultor to the Synod at meetings in Rome in June.

Final reports from the peripheries project are available online: https://migrants-refugees.va/resource-center/publications.

Watch the video for additional context: Wisdom from the Margins

RSVP to attend in person: https://bit.ly/3CIOLEt

RSVP to participate online: https://bit.ly/3yUKKvw

Systematic theologian Sr. Ellen Leonard, CSJ, is being remembered by the St. Michael’s community as a groundbreaking theologian of “irrepressible joy” who cared deeply for the Church, her students, the role of women, and her religious community.

Sr. Ellen died Thursday, August 18 at the age of 88, in her 71st year of religious life. Entering the Sisters of St. Joseph at the age of 17, she taught elementary school for many years before becoming one of the first women in Canada to study theology, earning her doctorate from St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology in 1978. Having served as a lecturer during the last year of her doctoral studies, Sr. Ellen became an assistant professor in 1978, an associate professor in 1982, and a full professor in 1991. She would remain a fulltime member of the Faculty of Theology until her retirement in 1999, at which time she became an emerita professor.

Her teaching and research focused on Roman Catholic modernism, and feminist and ecological Christologies. Her many publications include three books focusing on the modernist movement of the early 20th century: George Tyrrell and the Catholic Tradition; Unresting Transformation: The Theology and Spirituality of Maude Petre; and Creative Tension: The Spiritual Legacy of Friedrich von Hugel.

“Sr. Ellen Leonard was a great woman in many ways–in her teaching and leadership at the Faculty of Theology, and in her advocacy for greater inclusivity of women in the Church,” says Regis-St. Michael’s Dean Jaroslav Skira. “She was also a deeply kind person and I feel very privileged to have known her.”

Former student Mary Ellen Chown, who has written a chapter on Sr. Ellen in the work Claiming Notability for Women Activists in Religion, says, “I had the privilege of being a student in Ellen’s course on ‘Feminist Approaches to Systematic Theology’ in the fall of 2000. What stays with me is Ellen’s deep respect for each of her students and her enthusiasm in sharing the rich diversity of global voices in feminist theology. Ellen’s teaching methodology encouraged us to reflect on our own life experience as a source of theology while integrating an academically rigorous feminist critique into our understanding.”

Sr. Ellen’s colleague, eco-theologian Dr. Dennis O’Hara, wrote the citation when the University of St. Michael’s College awarded her an Honorary Doctorate of Sacred Letters in 2014.

“For me, Ellen was an outstanding and compassionate educator, a skillful and kind mentor, a thoughtful and experienced colleague, and a dear and valued friend,” O’Hara recalls. “She was an extraordinary positive influence in so many lives.”

Former University president Dr. Anne Anderson, CSJ, says it was “a pleasure and a privilege” while serving as the Faculty of Theology’s Dean to have Leonard as a member of the Faculty.

“Ellen coupled her studies in Modernism with the teachings of Vatican Two and began to write and publish in the area of ‘Experience as a Source for Theology.’ The injunction of Vatican Two to “read the signs of the times” supported her life-long interest in the development of feminist theology as well as the scholarship of those who were writing and researching in this area,” Sr. Anne says. “Ellen also viewed ecological issues as one of the signs of the times that required careful attention. As a colleague, Ellen was an unfailingly generous supporter of the Faculty of Theology and its mission. Her many students received her full attention and support as well as the benefit of her continued scholarship.”

Sr. Ellen’s efforts will continue to inspire those who knew her and her work, says Chown.

“Ellen’s prophetic wisdom abides in her significant body of work, in her ongoing inspiration in the lives of her students and in the work of the Catholic Network for Women’s Equality (CNWE), which she founded in 1981, and for which she remained a lifelong mentor and supporter,” she says. “I will remember Ellen as a woman of transforming faith and grace who embodied hope for a renewing, inclusive Catholic Church, for justice in the world and for the flourishing of all creation – a woman who engaged this sacred work with integrity and an irrepressible joy.”

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to Fontbonne Ministries and you can click here for more information.

Each year, the Faculty of Theology marks the end of the winter semester with the Commissioning Mass, during which prayers are offered for all graduating students as they head out into the world to share what they have learned.

This year, Myungsook Kim, who will graduate with a Master of Theological Studies degree, offered a reflection. For the past 20 years, she has been teaching students with special needs in Catholic schools. Myungsook is a mother of two, and advocate for people who are physically and intellectually challenged, and an associate in the Felician Sisters Congregation. A former visual arts instructor at Gangneung-Wonju National University in South Korea, Myungsook immigrated to Canada at the age of 32.

Thank you, Student Life Committee, for allowing me to speak on behalf of graduates, even though I am far from the mainstream.

I have studied in the MTS program on a part-time basis for the last six years. I mostly took night classes because I have a full-time job during the day. Some people asked me why I was working myself this hard day and night. But for me, being a student at St. Michael’s was filled with joyful moments. Let me briefly tell you why.

First, the snacks! Previous SLC president Josefine prepared snacks for night students. After a long day at work, I drove down to class from Mississauga in the middle of rush hour. The joy of sharing snacks among classmates before the class in the lounge made me feel full of love. Thank you, Josefine, and the whole SLC for your love and leadership.

Second, “Aha” moments. Every lecture, every reading has cultivated me to transform. Sometimes, my brain froze with new and true information. Thank you, all professors and librarians, for being for us real-life models of disciples walking in the company of Christ on the road to Emmaus. You all have shepherd the “Aha” moments with love and care.

Third, transforming into an angel. My ministry practicum at the Felician Sisters’ house was special. It is home to 21 retired sisters enjoying their remaining lives while waiting for God’s calling to be with Him. They called me an angel for helping them with their basic physical hygiene needs. Sometimes, I simply hold their hands while they are passing. I felt I was walking in the company of Christ as well, like a blessed angel.

Lastly, overcoming obstacles together. The pandemic arrived and we all had to rely on the Internet. The special COVID funding arranged by St. Michael’s to help with pandemic expenses has provided us not only financial support but also the love of being cared for. Together, we all successfully thrived through our own unique way.

Thus, on behalf of the Faculty of Theology BD graduates of 2022, I thank the entire community of St. Michael’s for guiding us, for walking with us in the company of Christ, and for helping each of us to share our unique gifts.

Upon completing our degree, regardless of what our future holds, let us be sure to use our unique gifts that have transformed us here at St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. May we share God’s compassion, truth and love as we continue to walk in the company of Christ.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Dr. Brian Thornton worked as an accountant in 17 countries on four continents. Then he came to Canada and St. Mike’s. A few months ago he successfully defended his doctoral dissertation.

Synodality, Laity, Pope Francis—What’s It All About?

Pope Francis recently called a synod—a meeting of Church leaders—which opened in October and runs until 2023, and includes local consultations as well as meetings in Rome.

Pope Francis has declared that synodality is what God expects of the Church in the 21st century. He has put his own transformative stamp on the meaning and conduct of synods, saying that a synod involves mutual listening in which everyone has something to learn.

Synods are not new. They have been around since the early days of the Church. History records that bishops of neighbouring churches in the second century gathered together to find solutions to their common problems. It was not always stated when or if the laity participated. We know, for example, that bishops, presbyters, deacons and laity attended the Synod of Elvira around about the year 305. The Synod of Whitby in 664 was convened by a layman, King Oswiu, who ruled that the decisions of the synod were to apply in his kingdom. A modern historian has written that Vatican I (1869–1870) was the first ecumenical council “without direct lay participation.”

The irony is that, 10 years earlier, Father John Henry Newman had famously written about the necessity of consulting the faithful in matters of doctrine. In 1917 the Code of Canon Law limited attendance at diocesan synods to priests and bishops. But the Code left ajar the door to lay participation. It allowed diocesan bishops to invite “others” at their discretion, but did not define “others.” Shortly before the end of the Second Vatican Council in 1965 Pope Paul VI established the Synod of Bishops as a permanent institution. Attendance was extended to representatives of religious institutes and to “clerics who are experts.” There was no provision for lay participation.

Then, only eight days after the formal close of Vatican II, the Bishop of London in Ontario made a startling announcement. His diocese was to hold a synod, to which everyone in the diocese— clergy, religious and lay—was invited. He was not concerned that the laity would be in the majority; indeed he welcomed it. He was bent on letting the people of the diocese absorb and receive the teaching of the council. And he planned to be a listening bishop. He used this phrase often for he wanted to hear the opinions of the people on how the diocese should move forward. The voice of the people mattered because he took seriously what the council had taught him about the infallibility of the people of God. His other oft-repeated remark was that the Spirit would speak where the Spirit wished to speak.

More than half a century later this pioneering diocesan synod can be seen in conformity with the call of Pope Francis for a synodal church. Everyone in the church, clergy, religious and lay, has to listen to the others in order to discern the will of the Spirit. It requires an act of faith which is based on the conviction that God is at work in world history. Francis referred to the prophet Elijah who learned that the Lord was not in the wind, nor in the earthquake, nor in the fire, but rather in a tiny whispering sound. “This is how God speaks to us,” said Francis, and “we need to open our ears to hear that tiny whispering sound.”

Since his election Pope Francis has convened synods dealing with the family, young people, and the Amazonian region. Bishops, priests and laity attended them all in limited numbers. Now Francis has launched a synod of the whole Church. It is an ambitious project which will last two years, until 2023. Francis wants to hear the voice of the entire Church, so this synod is an exercise in mutual listening. It starts in the dioceses where all are invited to offer their thoughts and opinions. Each diocese will forward a synthesis to the local bishops’ conference. From there a further synthesis will go forward to the Synod of Bishops in 2023. After that the action moves back to the dioceses for the implementation phase.

Pope Francis opened the synod in October this year. He felt sure that the Spirit would guide the church and “give us the grace to move forward together, to listen to one another and to embark on a discernment of the times in which we are living.” He stressed that the synod was neither a parliament nor an opinion poll, but an ecclesial event. “If the Spirit is not present there will be no synod.” He emphasized the participation of all because participation was a requirement of the faith received in baptism. Baptism was our “identity card,” and his call for all to participate includes those on the fringes. “Enabling everyone to participate is an essential ecclesial duty,” he said.

The subject of this synod is synodality. When we place that alongside two prominent sayings of Francis, a diverting discovery emerges. Firstly, says Francis, synodality is the way of the Church in the 21st century. Secondly, the point of a synod is to discern where the Spirit is leading the Church. We can see then that Francis is inviting the Church to consider and discern synodality, the very subject that is at the heart of his pontificate. He has thrown it wide open. This is a valiant venture with an uncertain end result.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Dr. Hilda P. Koster is an Associate Professor of Theology and Director of the Elliott Allen Institute for Theology and Ecology.

Of Heatwaves, Floods and Climate Change—Our Kairos Moment

What could have been a summer of cautious optimism about life post COVID-19 has unfortunately become a summer filled with climate change-related horrors. Wildfires due to the record-breaking temperatures and a prolonged drought in the Pacific Northwest took human life and destroyed homes. It also ravaged thousands of acres of forest and seriously endangered marine wildlife. In Northern Europe, including in my native country, The Netherlands, torrential rains caused unprecedented flooding and mudslides. In South Madagascar, off the coast of East Africa, the worst drought in four decades is driving more than a million people into famine.

While the connection between climate and weather is complex, climate scientists agree that the heat waves and rains of this past summer are clearly linked to anthropogenic changes to the climate. What has scientists alarmed, however, is not that there is a connection between extreme weather events and climate change but that these events have been so severe and prolonged. Harvard environmental policy professor John Holdren, who served as senior adviser to former U.S. President Barack Obama, observes that “[e]verything we worried about is happening, and it is all happening at the high end of projections, even faster than the previous most pessimistic estimates.” (Los Angeles Times, July 21). The world truly is running out of time and many people seem to sense this.

The Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew has called the climate crisis a Kairos moment for our churches and the world: “For the human race as a whole there is now a Kairos, a decisive time in our relationship with God’s creation. We will either act in time to protect life on earth from the worst consequence of human folly, or we will fail to act.” (Closing Address to Symposium on the Arctic, 2007). The Greek word Kairos means the right or opportune moment. From a theological perspective Kairos indicates that time takes on a holy urgency. Time is no longer simply linear time, stretching open towards the future. Instead, it becomes critical to act. Calling climate change a Kairos moment thus marks the present as a moment of truth and opportunity; a moment where our collective response will have far-reaching consequences.

This fall the eyes of the world are on the 26th UN Climate Change conference in Glasgow (Scotland). COP26 is meeting with the urgent task to implement the climate commitments of the 2015 Paris Climate Accord, which seek to limit the increase of the planet’s temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The question before us then is whether the world community (especially the world’s wealthiest nations) can seize the moment of pandemic recovery as an opportunity to enact the necessary climate policies. For if we fail to grasp this moment and do in fact return to pre-pandemic rates of fossil fuel emission the world could be 1.5̊ Celsius hotter than it was prior to the industrial revolution as soon as 2030 and on track for much higher temperatures.

It is tempting to be skeptical about international climate conferences. After all, the world has passed many climate thresholds since the first UN climate conference in 1992. Climate change, however, is not just a political challenge; it is also a theological and spiritual one. In fact, our response to climate change touches upon the very core of Christian witness. For according to the Biblical tradition, God did not just create the world but also called it good. The Hebrew word for good, tov, means more than “good.” It implies a goodness that is life furthering, a life-generating capacity. Human induced climate change does not just go against this life-furthering capacity but is also undoing it. For those of us living in climate privileged communities, despair, resignation, or indifference are therefore not an option. Instead, we are called, in Pope Francis’ words, to an ecological conversion —that is, a change of heart in the way we look at, interact with, and behave towards the more-than human world with which we are entangled and on which we depend.

Kairos language keeps open the possibility of such an ecological conversion. It is stubbornly hopeful. In the Book of Revelation, John of Patmos sketches doomsday scenarios that eerily resemble those of our day. Yet with all its woes, Revelation does not foreclose the possibility of repentance (metanoia) and turning around. According to the New Testament scholar and eco-theologian Barbara Rossing, the catastrophes depicted by John are neither willed by God nor follow a cosmic destiny. In Revelation, God laments the state of the earth yet places the Christian community at an ethical crossroad (a Kairos moment) where it needs to choose between the polluting, death-dealing powers of Rome/Babylon or God’s New Jerusalem. While time is of the essence, John holds out the hope that the world will listen to the witnesses he so powerfully invokes towards the end of his book. It is significant, too, that Revelation ends with an attractive vision of the tree of life. There is no return to Eden, but there is a vision of what is possible. A vision rooted in the beauty and resilience of planetary life and in practices of an alternative political ecology, symbolized by the city-garden.

Many have heeded Pope Francis’ call for an ecological conversion. This September several religious communities and interfaith groups are embarking on a pilgrimage to COP26. They are visionary witnesses. Those of us outside the United Kingdom and Scotland are invited to add our own witness by walking to a special place or spot near us, posting our pictures and messages #Walkingtheland2021. Our messages will be collected and shared with delegates at COP26. In a time such as this, a time in which the world is running out of time, I invite all of you to participate in the Walking the Land project at https://www.pilgrimagefornature.com/walking-the-land and add your voice, dreams and hopes for our life together on this fragile planet.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Dr. Cynthia Cameron is the newly appointed Keenan Chair of Religious Education and Assistant Professor of Religious Education in the Faculty of Theology. Prior to coming to St. Mike’s, she taught undergraduate students at Rivier University and graduate students at Boston College and Loyola University New Orleans. Her research focuses on adolescence, particularly female adolescence, and the history and mission of Catholic schools.

Pandemic Safety and the Classroom

“I don’t want to see my students as threats.”

This was the anguished comment from a Catholic high school theology teacher in a graduate religious education course last summer, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. We were discussing the challenges and opportunities presented by teaching during the pandemic and, in particular, the possibility of Catholic high schools returning to face-to-face instruction in the fall of 2021. This student’s entreaty struck a chord with the class.

On some level, this reflects a common problem in schools. The busyness of planning for in-person teaching leads to a tendency to treat students as pieces in a complex puzzle. The task for educators is to figure out how to arrange the pieces so that students can be in classrooms efficiently and, now, safely. A rather de-humanizing perspective on the young people in our classrooms.

But, more importantly, these teachers were reflecting on how the push to in-person instruction— often decided on without much input from the teachers themselves—made them feel unsafe. The students, as potential carriers of the coronavirus, were threats to the physical safety of teachers. At this point in the pandemic, at least in the United States, it seemed that children and adolescents contracted the virus at lower rates and tended to suffer milder cases of COVID when infected. Which was, of course, good news. However, teachers are adults and, as such, were at greater risk from the virus. And, teachers were being asked to take on this significant risk in order to teach in a face-to-face environment. All over the US, some teachers decided the risk was too great, that their students were a threat, and some even left their jobs.

For the students in my class—all dedicated, but relatively novice, Catholic high school teachers—this led to a fascinating conversation about how we think about, talk about, and treat the adolescent students in our classrooms in a time of pandemic. What happens when we think about our students as threats? How can this not change the ways that we relate to them? And how can Catholic theological anthropology guide us in resisting this kind of thinking?

Theological anthropology is the branch of theology that wonders about what it means to be a human person created by God and in relationship with God and others. This is where the Church reflects on the meaning of our humanity. The two doctrines that most often come up in contemporary Catholic theological anthropology are that we are created in God’s image and that God took on human form in the person of Jesus. The first of these doctrines—that we are created in God’s image (Genesis 2:26-27)—suggests to us that there is something about humanity that reflects the reality of the divine, that we are like God in some way, that humans reveal in some small and imperfect way what God might be like. And, importantly, since God created humanity in God’s own image, humanity is fundamentally good. The second doctrine—that God became human in Jesus (John 1:14)—also points to this fundamental goodness in humanity. For God to take on the human condition suggests that God thinks highly enough of the human condition to be concerned for humanity. In Jesus, God is telling us that humanity is taken on by God, loved by God, and saved by God. So, drawing from these two doctrines, we can be comfortable saying that humans are created by God and loved by God and that there is goodness in our humanity.

But humans have historically struggled to act as if we are fundamentally good. We don’t always treat one another and ourselves in ways that reflect our theological commitments to the fundamental goodness of humanity. And, since teachers, even Catholic school teachers, can fall into this trap just as easily as anyone else, I often ask them to reflect on this question: “Are your students basically good or basically bad? Are they good kids who occasionally mess up or are they little monsters who need to be whipped into shape?” How a teacher answers this question reveals a great deal about how they will relate to their students. And, in my experience, the vast majority of teachers view their students as fundamentally good human beings, even when they are difficult or annoying.

But, how is this positive vision of the human person disrupted when the students become unintentional threats to the lives of the teacher? How are we to maintain and live out a conviction that they are fundamentally good if we are afraid of them? Does our conviction that they are fundamentally good mean that we have to ignore the threat that they may pose?

I don’t have any answers for my student or for any of us who found ourselves fearing our fellow human beings and the risk that they posed to us simply by existing alongside of us. On the one hand, the gradual reopening of things that has accompanied increasing vaccination rates in 2021 has started to lessen the need to think of my fellow human beings as a threat to my health and safety. On the other hand, as it has done with so many other issues, the pandemic has revealed to us the ways that we fail to live up to our theological ideals. The fact that we did think of our fellow human beings as threats is a challenge to all of us to think about what it means to love our fellow human beings, who are created by and loved by God, who are fundamentally good.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Colleen Shantz is Associate Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins in the Faculty of Theology and cross-listed to the Department for the Study of Religion, University of Toronto. Her research explores the formation of Christianity in the first three centuries CE and especially the role of affect, ritual, and religious experience in the origins of Christianity. She teaches a course on the foundations of justice in the gospels, which is where she first got to know Michael Iafrate.

Between the Present and the Hoped-for Future: Reflecting on the Life of Michael J. Iafrate

Last week a memorial service was held on campus (and Zoom) for Michael J. Iafrate who died in May of this year. Michael was a doctoral student at the Faculty of Theology, beloved to friends across the continent, a prophetic voice in the Catholic Church, a gifted singer-songwriter, a father, partner, brother, and son.

Such a list of roles may seem pro forma in a reflection on a life, but I muted it—considerably. Let me add just two more characteristics to illustrate: Mike was also a committed Weird Al fan and the lead author of The Telling Takes Us Home (2015), a call to justice that is intimately tied to the work of the Catholic Committee of Appalachia (CCA) where he was Co-Coordinator. Few lives encompass such breadth of passion.

Mike’s death came unexpectedly. He was just 44 and he left behind his three young children and his spouse, Jocelyn Carlson, after being diagnosed with leukemia about 6 months earlier. But his death violated expectations in another way, simply by being so out of sync with the size and vitality of his life and the work of justice ahead of him. His work with CCA regularly engaged coal mining in West Virginia, especially its effects on the dignity of labourers, care for the environment, and attention to the poor and vulnerable. You may recognize these three themes as central to Catholic Social Teaching. Mike gave urgent voice to their intersecting effects for the people of West Virginia.

Perhaps without realizing it, I think that many of us who knew Mike had invested in the future of his work for justice. Every day that he took up those causes—sometimes in the face of significant opposition—he helped me, among others, to hope that better conditions were possible. When we saw him pursuing justice, we saw a bridge between things as they are now and the world as it should be. Often, we fallible humans don’t realize we’ve been depending on such links between reality and hope until our expectations are violated.

Of course, Mike’s death also came in the middle of an even larger set of meaning violations: a pandemic, for goodness’s sake; a more urgent awareness of the pervasiveness of racism; and here, in Canada, the devastating proof of genocide and the failure of episcopal leadership to respond meaningfully. Many of the links between our values and expectations, and the realities of the world have been fractured during these past months. To borrow an image from Romans 8, the earth itself groans with grief for the children who were harmed as it groans in the degradation of strip mining.

In fact, that section of Romans was one of the readings from the memorial service for Michael. In Romans 8:18-27, Paul talks about the whole of creation groaning as it waits for liberation: “Even we—who have the first harvest of the spirit—even we groan within ourselves longing for our adoption, the liberation of our bodies. …However, hope that is seen is not hope—for who hopes for what they already see?”

To the degree that Catholic universities are formed by principles of Catholic Social Teaching, they can also generate such bridges between the present disorder and what we only hope for. When we foster attention to human dignity, for example, not only in what we teach but how we teach it, we better prepare people to create the pathways between the present moment and the liberation for which the world is aching. I give thanks for the way our brother Michael Iafrate lived into that vision in his particular, powerful, complex, too-short life. May many more like him be nurtured through relevant and hopeful education.

Read other InsightOut posts.

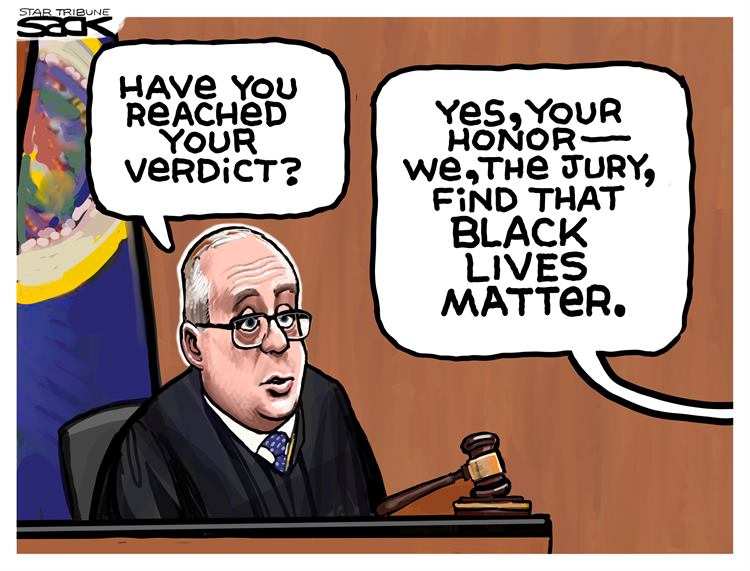

Theology students have the opportunity to enrol in an exciting new Faculty class: Black Lives Matter in the Classroom. The course, originally scheduled for last winter, was moved to the intersession, making it more accessible for our Master of Religious Education students, although this will be an offer of interest to students in various degrees across the Toronto School of Theology.

Black Lives Matter in the Classroom is a Basic Degree-level course to be taught by Dr. Marie Green. It will address how educators can become better aware of—and better able to respond to—systemic injustices facing Black students at school.

Many who see the course title Black Lives Matter in the Classroom may think of it as a unit coming out of OISE, but Dr. Green sees a strong theological underpinning to her course, and an equally strong justification for teaching it at a faculty of theology.

“In the eyes of God Black lives matter. We are all created in the image and likeness of God. The Black Lives Matter movement is, at its core, a human rights movement so it is absolutely possible—and necessary—to view this course through a theological lens.

“In this course we will challenge beliefs, assumptions, approaches, and biases,” says Dr. Green, who was awarded the Faculty’s 2020 Governor General’s Award. “Everyone has biases, and students will reflect on their impact on the classroom, and hopefully become motivated to be agents of change.”

Along with the usual readings and lectures, Green says classes will also feature guest speakers who can offer up tangible examples of equity and inclusive education. She says these examples will be particularly beneficial to those who do not have a lived experience of racism, or an understanding of the intergenerational harm of the legacy of slavery and other racist historical realities.

“We know that there’s a legacy of racism in Canada, and to deny that is to ignore the impact of residential schools, segregated schools, and more recently, streaming practices in public schools.”

The legacy, Green points out, manifests itself in many ways. Black students continue to be underrepresented in post-secondary institutions, for example, while also experiencing a significantly higher rate of suspensions in high school. At the same time, many Black high school students find themselves discouraged by teachers and administrators from pursuing more academic streams, limiting their future opportunities.

“We have seen violence against Black bodies so overtly displayed on our streets in recent times,” Green says, “but there is a different kind of violence taking place in our schools and classrooms. It is the violence of low expectations, lack of validation, and lack of cultural affirmation. This course will equip educators and other practitioners with resources to help them apply the critical theory perspective needed to support Black student success.”

With a topic so clearly in the public eye following a year of protests, Dr. Green expects difficult but constructive conversations where everyone has something to contribute and something to learn. “One of the benefits of teaching online,” she says, “is the ability to use Zoom breakout rooms, allowing students to have meaningful and engaging discussions, with the instructor able to visit all groups.

“I want to share tangible tools that all participants can use to address topics of equity and justice,” she says, “which is absolutely critical for student success.”

SMP3416: Black Lives Matter in the Classroom will run Tuesdays and Thursdays from 18:00–21:00, beginning July 13 and ending August 5.

Part of the communications team, Catherine Mulroney studied English and Medieval Studies at St. Mike’s and returned recently to complete an M Div at the Faculty of Theology.

A Shot in the Arm

“Love hurts,” the old song says. But a little short-term pain for long-term gain is always worth it—and especially in these unusual times.

A few days ago, I joined the millions of Canadians now vaccinated. I got a shot of Pfizer and, in the spirit of full disclosure, it didn’t really hurt at all, but for a little site tenderness that lasted all of 18 hours.

My injection moment made me want to recreate Rocky’s famous run up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, or Braveheart’s freedom speech, or Gene’s Kelly’s iconic “Singin’ in the Rain” dance because had been so long in coming and meant so much.

In truth, though, the only thing I did do was get a little teary-eyed because taking 20 minutes out of my day meant I was now one step closer to seeing my children again, a little bit closer to getting back to my real office, and I could now say I was helping in my own small way to end the nightmare we’ve all been living for more than a year. I think I’d forgotten what a pleasant sensation relief can be.

I’m happy to say that my employer, the University of St. Michael’s College, has been supportive as vaccinations have been rolled out, encouraging staff and faculty to get a shot, and offering time off to attend vaccine clinic appointments. It’s a mindset that brings our 180 strategic plan alive for me.

In these days of the coronavirus, I am reminded that the 180 is not just a statement to hang on the wall but a reflection of a lived attitude. The references to such things as concern for the common good, the need to recognize the dignity of all, and our need to care for all creation actually mean something to all of us. Challenging times are bringing that to light. I see this in the professors’ concern for students’ wellbeing, and their understanding that, these days, support and encouragement trumps deadlines. I see it in the student life staff and volunteers’ outreach to students, ensuring they know about extra funding available during COVID or offering reminders to take a break and engage in self-care, informing students of how they can get extra emotional support if needed. And I see it in email traffic and Zoom calls where we are all beginning to realize, via expressions of longing to be together again, that we might all be a little closer than just colleagues.

Daily, I watch the very lessons lived out on campus that I learned in ethics classes while studying theology at St. Mike’s, or while reading the classics here as an undergrad. Life is beautiful and precious and we are called to do our best not only to respect and protect it, but to celebrate it, too. To me, that lesson includes getting a shot—for myself and for my neighbours. We are to live out the now oft-used phrase that we are all in this together. I’m proud to be an alumna—and an employee—of a workplace that practises what it preaches.

As strong as all these motivations are, though, my primary impetus for getting a shot was to ease my kids’ worries. Their dad died a week before the pandemic lockdown began, and the early warnings about the severity of COVID had them stressed about their mother’s health.

“We’ve just had one parent die. We don’t want to lose the other,” said the oldest, soon after the pandemic began, speaking as the now-elder statesman in his usual blunt fashion.

For the following six weeks, I only went as far as our garden, guiltily answering the door on occasions, but mostly watching the world pass by from our front window.

But then, early May dawned, and with it, my first solitary wedding anniversary. I felt an overwhelming desire to visit the garden centre and buy some plants, something that Mike and I had done in May for as long in as we’d been homeowners.

I can’t say it was a fun trip, as it was laden with guilt: guilt for co-opting my youngest into accompanying me on my covert operation, and guilt that I was contravening a heartfelt request from my children. On an up note, though, I felt 17 again, because it reminded me of being in high school and bending a few of my parents’ rules—just slightly, of course.

I monitored dropping age limits and expanding availability and leapt when my chance came. It took close to an hour on hold with the Ministry of Health to book an appointment, and the poor woman who answered my call had a wailing child in the background, but it was all worth it.

My kids put on a brave face at all times for their mother but I know they were relieved. I was just happy I could do something that would ease some of the pile of worries each of them has these days. Then attention shifted to when they could be vaccinated, too, jealous that Molly, the child living in Florida for the year, has already had both doses of Moderna.

This has been an extended period of loss for all of us. Some of the those losses, of course, are trivial—the inability to hit the links, or the discovery that not being able to go to the hairdresser’s means saying goodbye to a preferred hair colour.

And some, of course, are profound. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t lost a friend or relative in the past year, including some to COVID, with their grief compounded by the inability to say a proper goodbye.

That’s why the vaccine, along with continuing measures such as masking and social distancing, remain so important. A shot in your arm is a shot in the arm for all of us. Take one for the team.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Fr. Gustave Noel Ineza, OP, is a doctoral student at St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. Born and raised in Rwanda, he lived through the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi and went into exile for a month in what was then Zaire. His family left the refugee camps and returned to Rwanda after three members of his family developed cholera. He studied in the minor seminary and joined the Dominican Order in 2002. He studied Philosophy in Burundi, and Theology in South Africa (SJTI/Pietermaritzburg) and the UK (Blackfriars/Oxford). Ordained in 2014, he worked for Domuni (www.domuni.eu) and was a chaplain to university and high school students. In 2018, he came to Canada to pursue studies in Christian-Muslim dialogue. He is currently reading on post-colonial approaches to the taxonomies assigned to religious traditions (Muslims and Christians) by colonial powers in Rwanda.

Do We Need Someone to Die to Remind Us that Black Lives Matter?

Black lives matter! That was more or less the verdict, 11 months after the brutal killing of George Floyd by Officer Derek Michael Chauvin, and 43-day-long traumatic trial. Twenty-nine years and a month after the trial of four police officers who savagely beat Rodney King, the fear of an acquittal gripped American society used to police officers’ trials ending with disappointing verdicts and acquittals.

The trial finished ahead of the U.S. Senate vote on a bill on April 21, 2021 to combat anti-Asian American hate crimes. Racial tensions have spiked in the United States, tensions that followed the empowerment of white supremacists, a reality which reached a peak with the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, a gathering of racist groups that envied the 1930s Reichsparteitage or Nuremberg Rallies.

Four years prior to George Floyd’s murder, a 24-year old Malian-Frenchman, Adama Traoré, died, on his birthday, in police custody, after he was brutalized by French police. Since Traoré’s death, a huge debate has begun in France. Universalist leftist thinkers were scared that rhetoric that generalizes about police brutality might hinder the “Republic,” a chimeric ideal of French unity that assumes all French citizens are equal and equitably treated by the law. Realist activists, often represented by a courageous woman named Rokhaya Diallo, never stop warning the French that there is a risk of considering the American police brutality as something particular to America, because it is widespread in many European cities. Diallo, who seems to carry alone the Black Lives Matter movement on her shoulders, has become the black sheep of a denialist French media because of her positions. The French President’s attacks on “American” Postcolonial movements, “a catch-all term covering everything from anti-colonial thought to critical race theory, intersectional theory to Black Lives Matter,” highlight the persistent denial of oppression towards racialized minorities in many former colonial European powers. Protests to bring to justice Traoré’s murderers were met with brutal police reactions. France is deeply immersed in denial of its racist colonial past, which lives on in its treatment of racialized minorities.

Indeed, change may take several decades to come, even in the United States. After the verdict was announced, the U.S. Representative for New York’s 14th congressional district, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, wrote on her Facebook page: “That a family had to lose a son, brother, and father; that a teenage girl had to film and post a murder; that millions across the country had to organize and march just for George Floyd to be seen and valued is not justice. And this verdict is not a substitute for policy change.” Former U.S. President Barack Obama wrote that “true justice requires that we come to terms with the fact that Black Americans are treated differently, every day [and] millions of our friends, family, and fellow citizens live in fear that their next encounter with law enforcement could be their last.” Obama added: “While [the] verdict may have been a necessary step on the road to progress, it was far from a sufficient one. We cannot rest. We will need to follow through with the concrete reforms that will reduce and ultimately eliminate racial bias in our criminal justice system. We will need to redouble efforts to expand economic opportunity for those communities that have been too long marginalized.”

Japanese Tennis player Naomi Osaka, who grew up and lives in the U.S., tweeted these very heartbreaking words: “I was going to make a celebratory tweet but then I was hit with sadness because we are celebrating something that is clear as day. The fact that so many injustices occurred to make us hold our breath toward this outcome is really telling.” In other words, no reasonable person believes that the verdict on Chauvin’s crimes signifies the end of police brutality to Black people. It becomes even harder when some influential TV hosts, like Fox News’ Greg Gutfeld, made it clear they believe Chauvin may not be guilty. Gutfeld stated that the only reason he would want the verdict to incriminate Chauvin is because his neighborhood was looted last summer.

The whole idea of looking at Black people as a threat has been used to justify the discriminatory policing of Black neighbourhoods and unreasonable stop-and-frisks of Black people by law enforcement in the U.S. One highlight of the trial occurred when one of the prosecutors, Steven Schleicher, explained the difference between a threat and a risk. That some insecure white law enforcement agents, empowered by systemic racism in their institutions, might be inhabited by an unreasonable fear of black people transforms Black people neither into threats nor risks. That Brooklyn Center Police Officer Kim Potter, while training a rookie, had to pull a gun on Daunte Demetrius Wright for an outstanding driving ticket explains what may go on in the routine training of American police officers. The fact that she screamed “taser, taser, taser” while shooting him with a gun is also confusing. My training officer in my military service forgot to tell me about the usefulness of screaming “gun, gun, gun” while I am shooting at the target! The most surprising thing is the many peaceful arrests of white mass shooting perpetrators, such as Kyle Rittenhouse and Dylann Roof, which proves that police officers are trained in how to de-escalate tensions, even with highly dangerous individuals. Apparently, that training does not equally apply to people of colour.

One of the most racist whataboutisms on police criminal treatment of Black people in the U.S. is the objection phrased in these words: “What about Black-on-Black crime?” Black-on-Black crime is punished, sometimes beyond the realms of reasonable corrections. In almost all instances when police are accused of the summary execution of Black people, judicial institutions focus on police training guidelines. The fact that Black lives matter is not news to Black people. Black people who take other Black peoples’ lives know they committed a crime and that they would be seriously punished if caught.

The verdict in Chauvin’s trial does not end anti-Black racism. Orchestrated attacks on Colin Kaepernick’s knee may have ended but it will still take years before Black people start feeling safe anywhere around the police. I still get followed by the police in some liquor stores. When I am, I still have the luxury to bother them with words like: “Oh! Because you are here, can you help me find a Coudoulet de Beaucastel Côtes du Rhône Blanc and a Philippe Colin Chassagne-Montrachet, please?”—in a very French accent. However, most Black people are extremely bothered by their presence. An African American friend advised me to never ask them to fetch me a lemonade.

I think the Church must be careful in these times. When people marched against police brutality following George Floyd’s killing on June 1st, 2020, President Donald J. Trump ordered the peaceful dispersal of the crowds protesting near the White House so that he might stage a photo-op before St. John’s Episcopal Church. In a brilliant article for The Atlantic, Garrett Epps, Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Baltimore, called it “Trump’s Tiananmen moment.” However, the most alarming aspect is that President Trump chose to violate American citizens’ First Amendment rights so that he could take a picture in front of a church, holding a Bible. The following day, President Trump and first lady Melania Trump visited the Saint John Paul II National Shrine in Washington. While many religious leaders condemned the photo ops, Trump still managed to sow discord among Christians—those who thought his attitude toward protests against police brutality was godly versus those who were disgusted.

Many police departments have Christian chaplains, and law enforcement agents are members of our parishes. Just as Church leaders in the past transformed the pulpit as a place to theologically defend civil rights, it is a Christian duty that it become clear to all the faithful that to God, Black lives matter.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Fr. Gustave Noel Ineza, OP, is a doctoral student at St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. Born and raised in Rwanda, he lived through the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi and went into exile for a month in what was then Zaire. His family left the refugee camps and returned to Rwanda after three members of his family developed cholera. He studied in the minor seminary and joined the Dominican Order in 2002. He studied Philosophy in Burundi, and Theology in South Africa (SJTI/Pietermaritzburg) and the UK (Blackfriars/Oxford). Ordained in 2014, he worked for Domuni (www.domuni.eu) and was a chaplain to university and high school students. In 2018, he came to Canada to pursue studies in Christian-Muslim dialogue. He is currently reading on post-colonial approaches to the taxonomies assigned to religious traditions (Muslims and Christians) by colonial powers in Rwanda.

The Other Sister

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught many to value more highly essential workers who are usually underpaid after long hours of vital work. Nurses are among the most praised as they daily risk contracting the virus while trying to offer a treatment to the sick. It is not the first time that nurses, women in particular, have risked their lives to save other people’s lives during pandemics. Several pandemics affected the pre-modern world. Some of those who offered treatment to the sick were non-cloistered women religious whose identities have not been comprehensively studied. These women were part of bigger movements which flourished in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times.

In September 2020, I joined a team of academics as an assistant researcher to Dr. Alison More. Dr. More is the undergraduate Medieval Studies coordinator and the inaugural holder of the Comper Professorship in Medieval Studies at the University of St. Michael’s College. She works on a joint project with Dr. Isabelle Cochelin (Department of History & Centre for Medieval Studies/UofT), and Dr. Isabel Harvey (Department of Humanistic Studies of the University of Venice Ca’ Foscari). The project is called “The Other Sister” and its focus is “women who pursued forms of religious life outside of the cloister in medieval and early modern western Europe and New France.” The other members of the project are Dr. Angela Carbone (University of Bari Aldo Moro) and Dr. Sylvie Duval (Università Cattolica in Milan), research assistants Laura Moncion, Emma Gabe, and Meghan Lescault (Centre for Medieval Studies or Department of History/UofT), and Camila Justino (USMC Book and Media and Mediaeval Studies).

The women studied are known by many names, including beguines, tertiaries, recluses, oblates, secular canonesses, lay sisters, pizzochere, bizzoche, beatas, and others. Their names and forms of life varied according to location. Our research group organizes thematic meetings which are the main venue for discussing current research, and recent books, chapters in books, articles, both published and forthcoming. As the COVID-19 pandemic has affected people’s movements, presenters invited from different academic institutions around the world working on aspects of the project meet by Zoom each month. Although the situation has made it impossible for people to have actual face-to-face meetings, it has allowed those on different continents to virtually meet.

To date, the group has prepared and successfully conducted five thematic meetings. The first meeting was entitled Women Serving Enclosed Women (held on September 29, 2020), the second was on Working in Premodern Hospitals (October 27, 2020), the third’s theme was Charity, Caregiving and Female Social Roles from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period (December 17, 2020), the fourth was on Naming The Other Sister: Tertiary, Lay, or Penitent? (February 8, 2021), and the fifth was held on Medieval and Early Modern Beguines, from Provence to Northern Europe (March 15, 2021). Details about those thematic meetings are found on the group’s blog.

The attendance has recently been reaching about 40 participants, mainly professors, post-docs, and PhD students from around the globe, all interested in the subject. Our discussion inevitably yields new insights which cross the usual temporal and geographic boundaries.

The main group of the ten researchers attached to “The Other Sister” has working meetings where we prepare the rest of our activities: thematic meetings, workshops for larger audiences, a workshop for our members on using ArcGIS Software to create maps of the communities of non-cloistered religious women, the construction and development of a blog, etc. The blog is named “The Other Sister.” It presents an overview of research and has space for recent updates and news of importance or interest to our community of scholars.

On a personal note, with this project I am learning about historical methodologies that do not aim at proving hidden agendas but analytically and objectively examine all possible data. Also, I have gained a new perspective as a student in Christian-Muslim relations. My usual methodology is historical and postcolonial. It investigates silenced and othered voices in my country’s religious identity construction. I have learned much from “The Other Sister.” Apart from the finesse in the communication of the members and the rigour in the historical research with its requirements for accuracy, I have come to appreciate the academic enthusiasm involved in understanding subjects that touch a given identity. I am also interested in understanding the power relationship between identity and those who write history: in our case, the image given to these non-cloistered, lay-religious women by predominantly male and clerical historians.

Our work values the religious zeal of women who were willing to live a life given to the poor, the sick, prayer, and teaching, often in the face of incomprehension and negative judgment from their society and the Church. Some were considered heretics or witches simply for wanting to live this life outside the walls of a cloister. A deconstruction of the meta-narrative on them that at times portrayed them as uncontrollable dangers to the Christian faith aims to restore their proper image. As the Church strives to include women in its decision-making bodies, it will surely be inspired by the findings of “The Other Sister” project, and the genius of the women working on it.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Carla Thomas is a member of the Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine of Siena, based in Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies. She is a national of Guyana, South America, and worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for several years. Carla is passionate about young adult ministry and adult faith formation. She sums up her self-understanding as a Dominican by means of the following bible quote, “But how are they to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him? And how are they to proclaim him unless they are sent? As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!’” (Romans 10:14-15). At present, Carla is involved in parish ministry among Caribbean nationals in Toronto. She is looking forward to gardening again this summer and, hopefully, to visit a few more places in and around Ontario. She is a doctoral student in the Faculty of Theology and is developing a thesis prospectus at the intersection of family theology and ecclesiology.

This Is the Day the Lord Has Made

Alleluia! Christ is risen! This is the day the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad! Alleluia!

Dear Easter, it is wonderful that you are here again! You are truly one of the best times of the year and I delight in the signs of your presence everywhere. Thank you for bringing your friend, Spring. You began to alert me about two weeks ago that you were just around the corner when I noticed the new life springing up all around. The perennials have begun to emerge promising to bring a feast of color to the front lawn soon and I admit that I have been eagerly keeping an eye on the trees next door looking for the first sign of leaves. In this neighborhood, the children have begun to play on the sidewalk again and some parents have hung Easter eggs on trees. You are welcomed with joy for you bring re-birth, new life, hope and God’s promise of faithful love for the world.

As I reflect on the hope that this season represents two different kinds of events come to mind. First, in my homeland of Guyana, South America, Easter is kite-flying season. It is a national tradition that on Easter Monday families would spend the day outdoors enjoying a picnic and helping children to raise their kites in the air. I consider the sight of hundreds of kites dotting the sky throughout the day to be one of the most beautiful experiences of the Easter season. From an early age I learned to associate this event with the resurrection. Catechists used this local tradition as a symbol to help children understand in faith the biblical testimony that Jesus rose from the dead and that He is truly alive. While Easter is a Christian celebration, kite-flying is for everyone. On Easter Monday, social and political struggles are transcended as communities share in a day of fraternity, friendship and mutual goodwill. This cherished national tradition provides for the people of Guyana a glimpse of the reconciled unity and hope promised by the resurrection of Christ and articulated recently in Pope Francis’ encyclical letter Fratelli Tutti.

The second event is the Holy Saturday liturgy during which the Elect receive the sacraments of Christian initiation. Having served on RCIA teams in parishes in Guyana as well as Trinidad and Tobago, I would say that there is no greater joy that night than witnessing the baptism of new members who were preparing for that moment for at least two years, in most cases. Their faces are usually filled with peace and hope as they look forward to life as Christians. Indeed, the newly-baptised often become much more enthusiastic members of their parish communities than life-long Christians. Their journey as neophytes continues throughout the Easter season as they move into the period of the mystagogia until Pentecost. The RCIA renews parishes. In my case, the recitation of baptismal promises became even more meaningful when made in the presence of new members who were an inspiration for a deeper engagement with the faith. The celebration of the sacrament of baptism is one of the preeminent signs of hope at Easter.