A coming conference at the University of St. Michael’s College entitled The Other Sister: New Research on Non-Cloistered Religious Women (1100-1800), will shine an overdue light on the unique lives of women who lived demonstrably religious but non-cloistered lives outside of traditional monastic structures during the Middle Ages and beyond.

The regional names assigned to these single or widowed women sound today like exotic jewels: beguines, bizzoche, pinzochere are just a few examples, but often stemmed from very specific roles these women filled. And while there is ample evidence of their existence and the charitable work they conducted, they have often been overlooked in scholarly discussions because they fell between the more traditional lives of nuns and married women. One of the chief aims of the conference is to discuss where and how they fit into their times, both within the church as well as within society.

In part, says Dr. Alison More, who is one of the conference organizers and Associate Professor, Comper Professorship of Mediaeval Studies at St. Michael’s, one of the challenges these women faced is that since they didn’t lead traditional lives — monastic, wearing habits, for example — the church and society were unsure of exactly where they fit in and, thus, they were treated with suspicion, even while answering great societal needs.

“They’re not married and they are not nuns…There was a fear of sexual misbehaviour, heresy, or general misconduct” More says, noting that since these women were not the same as nuns, who were immersed in a cloistered, religious life of prayer, “therefore they must be up to no good.”

In fact, these women, often funded by wealthy widows or bequests, lived in loose-knit communities. They took on specific, practical roles, for example, as “sisters of the soup,” feeding the hungry, as hospice sisters or in the Low Countries, engaging in the cloth trade to fund charitable work, More says. They also served in North America, including New France, for example, educating children.

“Women were doing what needed to be done,” she says, noting that these women were asking themselves “how can I imitate Christ in an urban setting,” aware of the suffering and needs they witnessed in their own communities and wanting to respond.

“These women played a significant role in society” and managed to work within conventions by applying rules in creative ways, More adds.

The Other Sister conference, which runs May 18-20 at St. Michael’s, is a collaborative, international effort organized by University of Toronto mediaeval scholars, including Drs. More and Isabelle Cochelin and a group of graduate students, as well as Drs. Mary Doyno of California State University Sacramento and Patricia Stoop of Antwerp University.

The conference, More explains, grew out of an informal research group of academics pleased to find others working in the same field. During COVID, the group would hold Zoom workshops, where new research was summarized. Once the group neared 50 members it made sense to take the conversations to meeting in person, she says.

You can register for The Other Sister in person or via Zoom by contacting tos2023conference@gmail.com.

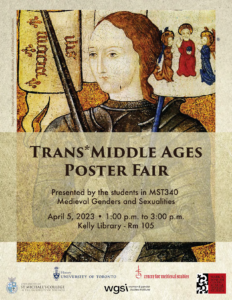

The Trans* Middle Ages Poster Fair taking place at the University of St. Michael’s College in early April aims to shed light on the rich and diverse experiences of trans people during the mediaeval period.

The goal, says Dr. Jacqueline Murray, who teaches the course Medieval Genders and Sexualities as part of the Mediaeval Studies Program at St. Michael’s, is not only to further inquiry into a historical area that has only recently gained traction but also to foster empathy and a greater ability to see the dignity inherent in all people.

“People think the trans experience is a modern phenomenon but as these posters will demonstrate this is not a new thing,” Murray says. “This course offers an inclusive understanding that there are – and have always been – many ways individuals experience and live their identity.”

The poster fair, which is the capstone project in Murray’s class, will see students working in teams to produce posters on a specific person, including many saints, offering evidence of a trans experience.

There are many benefits to students participating in a poster presentation, she says, because they engage in significant historical research to find the information they will display on the posters, and then develop creative ways to display that research to engage the visitors to the fair. Because this is a team project, students demonstrate their ability to work collaboratively. And when the posters are displayed at the fair, students will engage with attendees who have questions about their presentations.

All of the skills students develop in the creation of their poster are transferable, she adds, regardless of whether participants are moving on to further studies or into the workforce.

The work involved in preparing for the Trans* Middle Ages Poster Fair offers the added learning experience of tackling a research area that is just beginning to open up, demonstrating to our present society the importance of the past to understanding current human experience. The deliberate use of Trans* in the event’s title is designed to point to the variety of trans experiences, including social presentations of transvestism or drag to nonbinary and genderfluid identities.

“There are mediaeval medical treatises that address the premodern physical and social experiences of intersex people. There is plenty of documentation of women who dressed as men to receive an education,” Murray says, adding that some people who lived their lives as monks were found after death to have been biological women. St Joan of Arc, she adds, is likely one of the best-known people from the Middle Ages whose life suggests a trans experience.

Research into the mediaeval church indicates that it was a far less homogenous time than many assume, Murray explains, and it was not a time when the pope dictated to church members what to do and how to live.

“That is a myth to be dispelled,” she says, arguing that church of the Middle Ages embraced diversities that may surprise many people today.

Dena Abtahi, a 4th-year student majoring in Human Biology and Molecular Biology with a particular interest in medical equity, opted to enroll in the Medieval Genders and Sexualities course because, while she considered herself well educated in other historical eras, she wanted to know more about the Middle Ages, believing it helpful to have a historical understanding of the era to shed light on humanity’s progress as well as ways in which we have regressed. A bonus, she adds, was the opportunity to study with Dr. Murray, who is a leading expert in the field.

“In reading primary sources I was transported back to the era and studying persecution then led me to ask, ‘Is this person still persecuted?,’” she says.

Abtahi says she has learned from reading about the fears people felt at feminine men and masculine women and related issues, such as worries that women might be appropriating social or sexual masculinity.

“Despite obstacles and fears, people who knew they were different and presented differently were fighting for rights, just as women in my home country (Iran) are fighting for their rights regarding the hijab, for example,” she says.

Hilary Packard, a 3rd-year student with a double major in visual studies and mediaeval studies, says the Mediaeval Gender and Sexualities course enhances their minor in critical studies in equity and solidarity.

As someone who does advocacy work for trans people in sports, Packard says the course is intensely timely given, for example, the current movement in many jurisdictions in their native United States to restrict the rights of trans people.

“Trans people are being criminalized but they have been here all along and are part of humanity,” they say.

Packard points out that until recently there was little analysis available to those outside the realm of historians on the experience of women in the Middle Ages. Current work to move more specifically to examine the mediaeval queer experience will be similarly helpful in teaching us about the evolution of attitudes and experience, they add.

“There is something grounding in knowing your identity came before your own modern experience,” Packard says. “It is very positive.”

Adds Murray: “The take-away from this presentation and this course is an appreciation that knowledge and history can lead to empathy and to an acceptance of the ambiguities in life. Our goal is to bring the trans past into the present.”

The Trans* Middle Ages Poster Fair, which St. Michael’s is hosting, is happening in collaboration with Centre for Medieval Studies, the Women and Gender Studies Institute, the Mark S. Boham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies and the University of Toronto’s History Department, takes place April 5 from 1-3 p.m. in Room 105 of the John M. Kelly Library.

Abigail Lawson has spent much of her adult life travelling and relocating to different parts of the world. Raising her two young children in the Middle East and working as a photographer, she has travelled from countries such as the United Arab Emirates to Greece and Italy to Croatia, capturing weddings for clients around the globe. Abigail has recently returned to Canada after a 12-year hiatus from her studies. A Mediaeval Studies major, she is presently writing her senior essay on the exploration of practical mediaevalisms and their application in the classroom, examining how they might be presented to a student audience.

Courtly Love and the “Chick Flick”

“Lancelot followed her with his eyes and heart until she reached the door; but she was not long in sight, for the room was close by. His eyes would gladly have followed her, had that been possible; but the heart, which is more lordly and masterful in its strength, went through the door after her, while the eyes remained behind weeping with the body.”

Chrétien de Troyes, Lancelot, The Knight of the Cart

The label “chick flick” has been used to characterize a particular film genre for as long as I can remember. The pithy designation is recognizable and some might perceive it as a tad reductive, but I have to admit I love a good chick flick. The films offer escapism—a departure from societal norms—depicting romance through a utopian and often implausible lens. The premise of one film in the genre is typically a carbon copy of the following: handsome boy meets beautiful girl, boy and girl fall in love, unforeseen obstacle stands in the way of said love, a battle is fought and won, and the couple live happily ever after.

Although the idea of romance has evolved since the Middle Ages, many people genuinely believe that Cupid’s arrow will strike, and fate will bring them to their soulmate. We love dreaming of a fairytale ending. When that initial spark inevitably fizzles, some believe—sadly—that it must be over. Many of us are searching for that glittery romance repeatedly depicted on screen and in books —ignoring the possibility that this may only exist in fiction. Many men struggle with a hero complex and believe that to be respectable and worthy, they must “save” the woman they love—her knight in shining armour. Women today share more equality with their romantic partners, and finding a woman who needs—or better yet—wishes to be saved by a man can present challenges.

When considering medieval romance and its relationship to modern romance, it is evident that the game has changed; however, the feelings associated with love and romance have not. Romance is depicted as attractive, scary, and even magical in the modern world—just like an excellent medieval romance: “Love without fear and trepidation is fire without flame and heat, day without sun, comb without honey, summer without flowers, winter without frost, sky without moon, a book without letters” (Chrétien de Troyes, Cligès).

Romance, interestingly, has not always been a thing. It stemmed from the mediaeval concept of Courtly Love. The romance was a genre of high literary culture which blossomed in the 12th-century courts of the romance super-fan, Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. Courtly love, or fin’amor, highlighted nobility and chivalry, following a set of codes and behaviour for ladies and their lovers. Today, these notions exist in our minds with lines such as “Chivalry is not dead!” In romance literature, knights performed extravagant bravery and gallantry for idyllic ladies above their station. Within the narrative of mediaeval romance, we see idealized gender roles through stories rife with overt masculinity and impossibly high standards of beauty and innocence. The patterns of masculinity perhaps unlock mysteries of the past while explaining why the courtly tradition of the chivalric hero is not only very much alive but perhaps here to stay.

Courtly love was never fixed but always unpredictable because Cupid, the God of Love, often initiated it and not the lovers themselves. The epic tales were wonderfully cheesy—often heart-wrenching—depicting undying love, magic and romance. Is it possible that courtly love is to blame for our idealized perception of love? Although today we use words such as courtship, chivalry and romance, somewhere over the centuries our wires have been crossed because the mediaeval poets who first wrote tales of love and chivalry would likely find our notions of romance very different. Literary works from authors such as Chretien de Troyes, Marie de France, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Andreas Capellanus present a unique perspective on social dynamics found within Arthurian courts in the Middle Ages.

Did these stories represent escapism? Probably. The medieval world left little space for a true love story; perhaps the nobility’s only connection to romance was through fiction and fantasy, as courtly love was not associated with marriage. The constraints of a loveless marriage, favouring financial practicality over love, were conceivably a preoccupation found within courts. The confines of society dictated whom one married; therefore, the nobility was left to love from afar. As Andreas Cappellanus stated in rule number one of his Rules of Love, “Marriage is no excuse for not loving.”

Today we pursue a relationship to fall in love and share a bond with our romantic partner; in contrast, mediaeval tales of romance rarely expected their true love to reciprocate. We often associate love and romance with flowers, doves, and heart-felt gestures of devotion—or for this medievalist—stories of brave knights such as Lancelot and his catastrophic love affairs with Queen Guinevere. Our distorted associations with romance could be in part thanks to mediaeval courtly lovers and their impossibly romantic prose.

Have these tales tainted how we connect and identify with love and place undue pressure on the idea of finding “the one” and “living happily ever after”? One thing is sure: the romance genre—both mediaeval and modern—reflects our insatiable human desire to connect with the excitement and mysteries of love and passion.

Read other InsightOut posts.