For many in the Irish community in Toronto, the University of St. Michael’s College and St. Patrick’s Day go hand in hand. Alumni members from the 1970s and 1980s, for example, will remember legendary St. Patrick’s Day parties in the COOP that were so popular tickets sold out weeks in advance. And this year, the university is hosting an alumni reception after the St. Patrick’s Day parade on Sunday, March 20, to mark the beginning of the return to some semblance of social normalcy as COVID begins to ebb.

But the interweaving of the Irish community in Toronto and the university can be traced back to the early days of St. Michael’s, says Interim Principal Mark McGowan.

“St. Mike’s, Loretto College, and St. Joseph’s College were important institutions for the Irish community, and St. Joseph’s became a draw for Irish dignitaries as a place to give talks and to stay while visiting Toronto,” McGowan says.

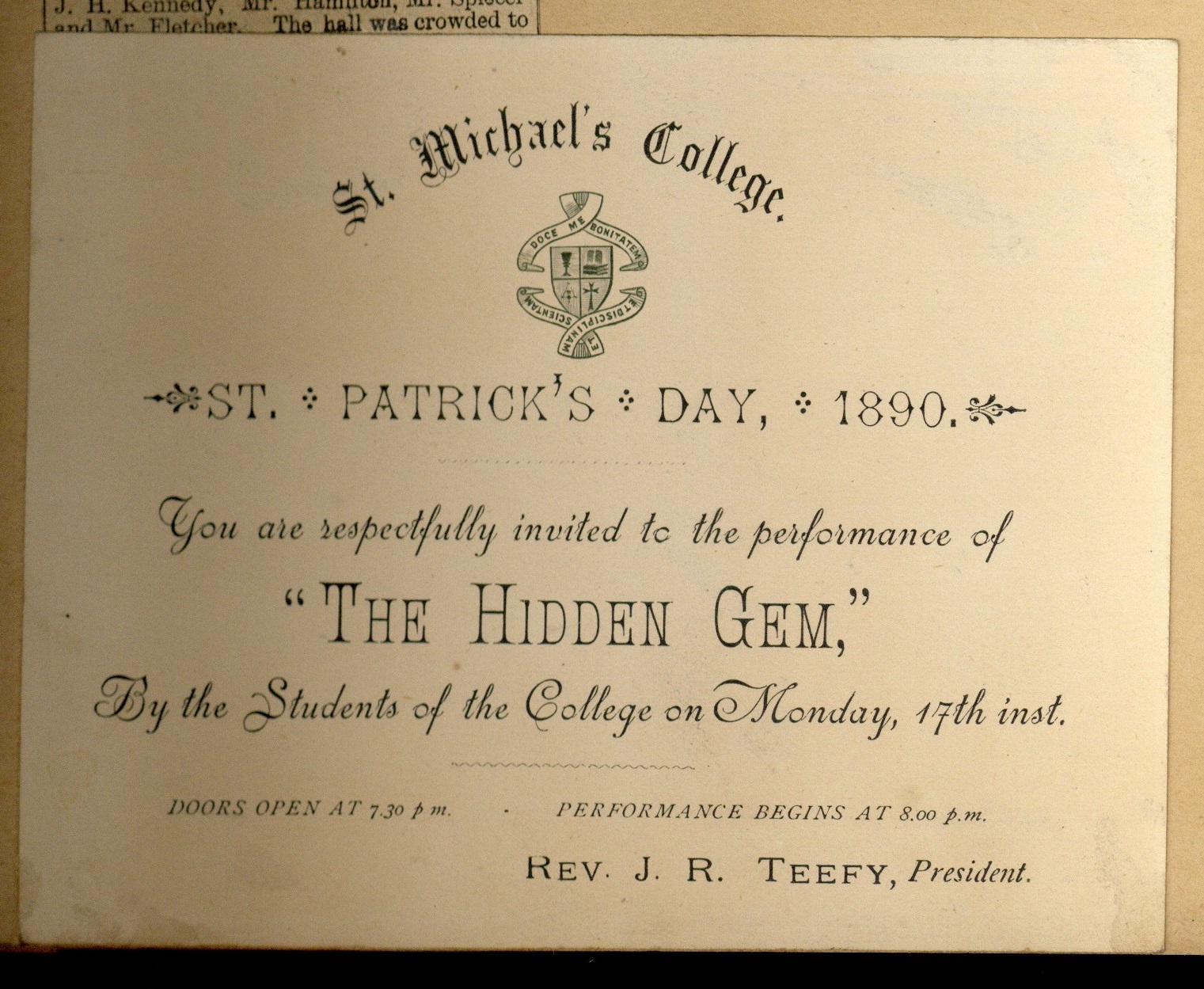

After 1877, the last year the first version of the city’s original St. Patrick’s Day parade was held, the seasonal attention turned to St. Mike’s for its annual St. Patrick’s Day concert—“pretty much the only game in town,” says McGowan, noting that attendees would then head home to private festivities.

As more and more Irish Catholics rose to prominence in Toronto—people like Francis Anglin, who was appointed to the Supreme Court, or brewer Eugene O’Keefe, who donated a substantial sum to build St. Augustine’s Seminary—it demonstrated to members of the Irish community that they could aspire to something more, and educating their children in a Catholic college became important part of that thinking, he says. St. Michael’s profile only grew within the community after it entered into federation with the University of Toronto in 1911, allowing the college to maintain control over history and philosophy classes, making St. Mike’s even more of a draw.

It was in 1975 that St. Michael’s took the first steps toward what would become the Celtic Studies program, when University President Fr. John Kelly, CSB, and English professor Dr. Robert O’Driscoll approached Dr. Ann Dooley, then doing doctoral studies at U of T’s Centre for Medieval Studies, and asked her to create an introductory course in Celtic Studies. An instant success, the course quickly led to more courses being created , with Mairin Nic Dhiarmada teaching the Irish Language, and Dr. David Wilson joining to teach history.

Over the years, numerous graduate students and graduates of the program have come back to teach as sessional instructors, and you’ll find graduates of the program and at schools such as Harvard, Trinity College Dublin, and at the National University of Ireland Galway.

Today, some students enroll in Celtic Studies courses because they are interested in learning more about family roots and Irish culture, says Pa Sheehan, who teaches in the program, but he notes that others enjoy the challenge of learning another language, one radically different from their first.

Students currently enrolled in St. Michael’s Introduction to the Irish Language class, for example, bring with them a range of first languages, including Portuguese and Japanese, Sheehan says.

Programs assistant Jean Talman, who’s been involved with Celtic Studies since 1990, recalls one former student whose parents had fled Vietnam after the end of the war enthusiastically joining the program and being billeted over one summer with a family on the west coast of Ireland, following up the next summer by staying in Wales.

While March tends to lend itself to thoughts of St. Patrick’s Day and Irish courses, Talman is quick to point out that St. Michael’s Celtic Studies program includes many courses that address Welsh and Scottish culture and literature.

“We’re a small but might bunch,” says Matilda Horton, president of the Celtic Studies Student Union, who notes that because the University of Toronto offers so many academic options, she has classmates who are linguists, or studying folklore, music or something entirely unrelated.

The student union works hard to build community, says Sheehan, who rhymes off a list of activities the students have hosted, ranging from Gaelic football to trivia nights, all open to any student so that those studying in other areas but interested in Celtic culture can participate and find people with like-minded interests.

Recently, for example, Dr. Ann Dooley offered a talk on St. Brigid’s Day, “captivating” her audience, Horton adds.

Over the years, the program has hosted some big names to speak on campus, including Irish writer Colm Tóibín and Irish poet Seamus Heaney.

“One of my favourite moments has been meeting people in class and them seeing them at a ceilidh in the COOP,” Horton says. “I realized how strong our sense of community is.”