A new course at St. Michael’s will take a deep look at the history and legacy of residential schools in Canada. Christianity, Truth and Reconciliation is offered as a First-Year Foundations Seminar and is open to all first-year students in the Faculty of Arts & Science in the University of Toronto.

A significant portion of the course will be the presentation of parallel histories: invitations to collaboration and mutual listening on the part of Indigenous leaders, and the all too frequent, tragic rejection of these amicable overtures by both church and state officials.

“My hope is that students come out of the course with the clear-eyed understanding of the way that European Christianity collaborated with the Canadian state to implement this program of cultural genocide—a clear-eyed view of the complicity in this project—but also a clear sense of other possibilities of relationship,” says course creator and Associate Professor Dr. Reid Locklin. The latter half of the course will also present ways that Indigenous Christians and Indigenous partners in conversation with Christians seek a creative rethinking of the Christian tradition on Turtle Island, the name many Indigenous communities call North America.

Locklin uses the term “cultural genocide” to describe the “total program” of the Canadian government to “exterminate Indigenous persons as Indigenous persons [and] remake them in the image of white Canadians,” a program in which Canadian churches were complicit. Because St. Michael’s is a Catholic university, the course responds to Calls-to-Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report directed at both churches and educational institutions.

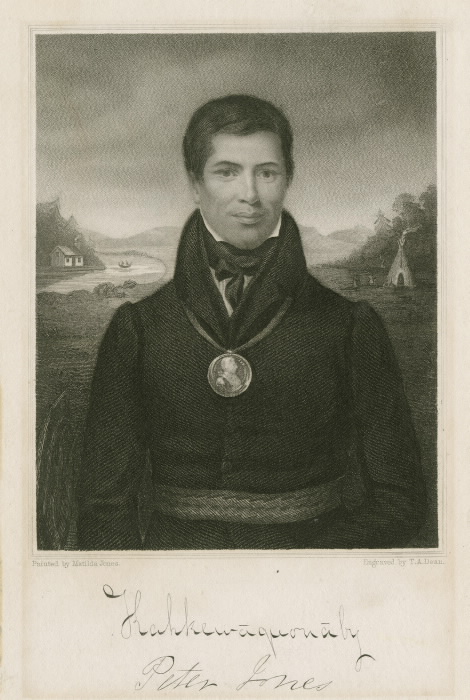

“We think about—one—do we have a place for looking at this history, particularly as a Catholic school, but also—two—how do this history and the rich traditions of knowledge in Indigenous nations and peoples have an impact on how we teach everything?” Locklin says. This second theme of the course opens a “less well told history of creative engagement of Indigenous persons and nations with Christianity,” including Sacred Feathers (Peter Jones), a Methodist minister and leader of the Mississaugas, and Louis Riel, a Catholic Métis who played an important role in the formation of Manitoba and Canadian confederation.

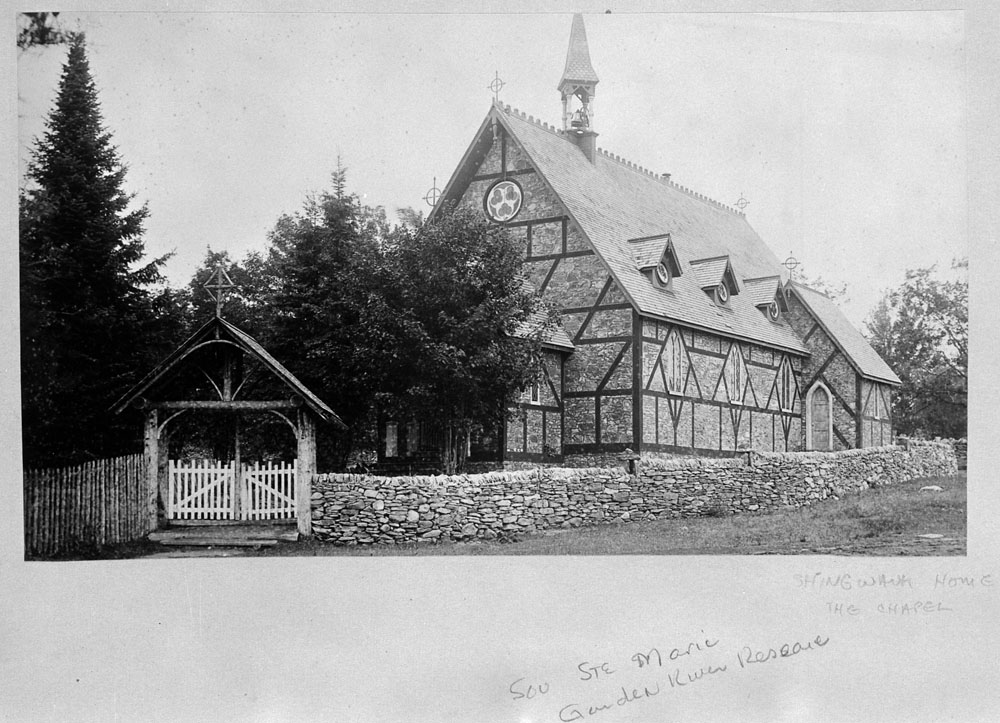

Bringing one of the course’s themes directly into its pedagogy, a key piece of Locklin’s course is a partnership with the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. Located at Algoma University, the centre maintains an archive of records related to residential schools across Canada, including both an Anglican-run residential school that operated on its grounds and a nearby Spanish Catholic residential school. The centre will make these archives available to students for research and exploration.

“The Shingwauk school was used by the state for cultural genocide, but when Anishinaabe leaders originally initiated the school they had a different, creative vision for what that school should be,” Locklin says, and that vision combined their own knowledge traditions with elements of European learning. The state’s dismissal of this opportunity for partnership is one of the “lost opportunities” he wants students to learn about in order to be able to see “the possibility of alternative pasts and alternate futures.”

Shingwauk itself is built on a model of partnerships with the Garden River Reserve and the Anishinaabe Nation, and when the centre was formed it established an advisory committee of residential school survivors. As part of Lockin’s final unit on apologies and reparations, students will have an opportunity to hear from a survivor panel. Locklin hopes that future students will be able to visit Shingwauk as part of the course.

There are lessons about this past available in the very ground on which St. Michael’s campus stands, and the course itself is one part of the University’s larger engagement with the Calls-to-Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Locklin received a grant from Arts & Science to create treatylearning.ca, a website that offers a non-Eurocentric revisionist history of the land.

Uncovering untold stories about the land St. Michael’s operates on is one aspect of a larger effort to accept rather than ignore an invitation to partnership, allowing Indigenous histories and traditions to reframe the University’s story. Other past related initiatives at St. Michael’s have included round table and blanket exercise events at the Faculty of Theology, reading collections in the Kelly Library, and reading groups for staff and faculty on Indigenous histories and issues.

“It is very important that a Catholic University address the Church’s engagement with Indigenous peoples in a meaningful way as a means of uncovering the truth, which is a necessary step to reconciliation,” says St. Michael’s Interim Principal and Vice-President Mark McGowan. “This seminar engages the students with primary sources relating to this Christian-Indigenous encounter and addresses the tough questions that have arisen from this history in Canada. A seminar of this nature is long overdue.”

Principal Randy Boyagoda is happy to offer credit for St. Mike’s new first-term check-in program where it’s due: with the students themselves.

The program, which offers students the opportunity to be matched up with professors to chat about adjusting to university life, is the result of an idea brought to the Principal’s Office by SMCSU, St. Mike’s student union.

With concerns over student mental health continuing to make headlines across the country, touching everyone from parents and professors to roommates and friends, Professor Boyagoda says he was pleased when a group of students approached him last spring to ask what St. Mike’s was doing to promote mental health.

“A delegation from the Student Life committee met with me and wanted to know what was being done locally,” he recalls. “They asked what St. Mike’s could do to respond. The challenge came from students.”

In ensuing discussions about what causes students worry or distress, one of the issues that came to light was students’ anxiety over meeting with professors, an experience that is pretty much unavoidable over the course of four years of a post-secondary education.

“Students were telling us they felt intimidated. Our goal was the humanize the relationship,“ he says.

Working to overcome that challenge seemed like a good – and feasible – first step, and so the first-year check-in idea took root with the goal of normalizing professor-student meetings.

A quick survey of professors – both at St. Mike’s as well as fellows associated with St. Mike’s – indicated a great willingness to help, and the program was launched to success this past fall. The University of Toronto has taken notice of the program and is considering broader applications, Professor Boyagoda notes.

“This program is not about course advising. It is totally voluntary, and student-centred,” he says.

First-year student Lisa-marie Lofty took advantage of the new program, and says she found the opportunity to chat with Dr. Felan Parker helpful as she adjusted to life at St. Mike’s.

“We met early in the semester as I was still thinking about courses and we had a friendly conversation about things to consider as the year went on,” she recalled.

As someone who had attended boarding school four hours outside of Nairobi and was drawn to U of T in part because of the appeal of a big city, it was nice, once here, to have another friendly face to relate to, especially as Dr. Parker told her a bit about his own experiences as a student.

Mathematics professor and St. Mike’s fellow Dr. Mary Pugh also participated in the program after a student contacted her. She says the main message she conveyed was that the student could contact her at any time.

The program “gives students access to a disinterested/non-judgmental person who’s well-familiar with the Faculty of Arts & Science and its classes and programs; someone who can treat them like a human and offer support/advice if needed,” Dr. Pugh says.

As helpful as the program is proving to be for students, it is also proving to be educational for professors as well.

“Because I usually teach upper-year courses, I haven’t had much interaction with first-year students,” says Dr. Parker, who teaches in St. Mike’s Book and Media Studies program. “Contrary to popular myth, I’ve found that they are the opposite of entitled, frequently apologizing for asking for help and uncertain of what kind of support is available. My hope is that the first-year check-ins, along with other initiatives like the first-year foundations seminars, will help show students that we are here to help.”

Social worker Nicole LeBlanc, St. Mike’s in-house wellness counsellor, says first-year students can experience anxiety for a number of reasons. Everything from worry over marks and making friends through to loneliness and being far from home can make students feel anxious or depressed – or both.

“Students face a lot of pressure these days, whether it’s competition to get into graduate programs or wanting to please parents, or worry over expenses. Add in relational issues – the rules of engagement over dating and friendships, for example – and it can be very challenging,” she says. “Many students are going from being a big fish in a little pond to a little fish in a very big pond, no longer having the top marks or profile they might have had in high school. It’s a shock to the system.”

“Be open and honest,” she says when asked what others can do to help. “Tell the person that you notice a change, and let them know that you care. You can suggest counselling or a doctor. Destigmatizing mental illness is very important.”

LeBlanc offers one-on-one counselling for St. Michael’s students, and notes that all it takes is an email or call to set up an initial appointment with her. She finds that a significant part of her role is letting students know what services are available, whether it’s academic help via the writing centre or learning strategist, social support from places like the Centre for International Experience, a referral to the Health and Wellness Centre at the University of Toronto for medical issues, or friendly encouragement to take advantage of on-campus activities offered through St. Mike’s Student Life.

If you or someone you know is in distress, you can call:

- Canada Suicide Prevention Service phone available 24/7 at 1-833-456-4566

- Good 2 Talk Student Helpline at 1-866-925-5454

- Ontario Mental Health Helpline at 1-866-531-2600

- Gerstein Centre Crisis Line at 416-929-5200

- U of T Health & Wellness Centre at 416-978-8030.