With the successful launch of the University of St. Michael’s College Awards for Irish Heritage earlier this year, the next step is to get the word out to high school and elementary schools across the country to expand the project’s scope, connecting even more students with the history of the Irish in Canada while also offering them a taste of university life.

The University of St. Michael’s College Awards for Irish Heritage winners Diya Bhatti, Madeline Doyle, and Kate O’Grady, at the centre of each photo, accept awards from Professor Pa Sheehan, Janice McGann, Irish Consul General of Ireland in Toronto, and St. Michael’s President and Vice-Chancellor, David Sylvester.

Created in collaboration with the Embassy of Ireland and the Consulate General of Ireland, Toronto to mark Irish Heritage Month in March, the awards were designed to celebrate the important historic and continuing contribution of the Irish in Canada. Elementary and secondary school students were invited to submit projects—whether a written piece, visual art, or a multi-media submission– that explore and celebrate local Irish heritage.

The idea came out of conversations with various stakeholders, says Professor Pa Sheehan, who oversaw the awards’ roll-out and is already planning on how to engage more school boards from across the country and encourage more submissions for next year’s awards.

“It’ll be even better next year,” says Sheehan, who adds that the contest is a great way to introduce future students to what Irish studies is all about. “The Irish have had a big impact in this country and played a significant role.”

The story of the Irish can have an impact on and inspire all students, and entering the contest can helps sharpen a range of skills, from engaging in research and creative thinking to helping understand the experience of different cultures, he says.

The launch of the awards was timed to mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the Irish-Canadian journalist and politician who became one of the Fathers of Confederation. The presentation ceremony earlier this month coincided with a conference on campus hosted by the Canadian Association of Irish Studies.

Submissions were judged on originality, creativity, and quality. Projects were adjudicated by a panel from the university.

Janice McGann, Irish Consul General of Ireland in Toronto, attended the awards ceremony in St. Michael’s Charbonnel Lounge earlier this month.

John Concannon, the Ambassador of Ireland to Canada, sent along praise for the participants.

“I offer my warmest congratulations to all the students who participated and were recognized. Kate, Madeline, Diya, and Joanna, your dedication, passion, and hard work are a shining reflection of the rich traditions and enduring spirit of Ireland. You are the storytellers, scholars, and ambassadors of our heritage, and your achievements fill us with great pride,” he said.

Ambassador Concannon also offered his thanks to event organizers.

“A special word of gratitude goes to the St. Michael’s Celtic Studies Program and Professor Pa Sheehan for their outstanding work in coordinating the ceremony,” he said. “I would also like to acknowledge the gracious hosts, CAIS – Canadian Association of Irish Studies–and Dr. William Jenkins. Your ongoing commitment to promoting Irish studies and cultural exchange is deeply appreciated and makes events like this possible.”

One of the benefits of the contest is the opportunity for young students to engage with a university and gain a glimpse into university life, says Sheehan.

“Being on campus (for the awards ceremony) is exciting, and it allows younger students to begin to think about and understand what life at university is really all about,” he says. “University life can be insular,” he says, adding that events like the awards ceremony remind contestants that there is a social component to university life, too.

To learn more about the Irish Heritage Awards, read ‘Introducing St. Michael’s College Awards for Irish Heritage‘.

This March, the University of St. Michael’s College is celebrating its Celtic roots by showcasing many aspects of this rich and vibrant culture. The Basilian Fathers founded St. Michael’s College in 1852 to give the poor Irish immigrants, who comprised a significant portion of Toronto’s Catholic population at the time, access to higher education. Since 1979, St. Mike’s students could study the heritage of its pioneering students with the establishment of the Celtic Studies program. The program continues to earn international attention for its groundbreaking work, particularly in Irish scholarship.

The Celtic Studies program is bolstered through the support of its partner, The Ireland Funds of Canada, which is hosting its popular St. Patrick Day Luncheon. This year’s event will take place on March 7 at the Fairmont Royal York and will draw a large crowd. Among those in attendance will be Janice McGann, the Consul General of Ireland, Toronto. Proceeds from the luncheon will support the Ireland Funds of Canada endowment in the Celtic Studies program.

“Celtic Studies offers students an unparalleled opportunity to research and explore Ireland’s cultural legacy and its profound global influence, all of which is made possible through our partnership with the Ireland Funds of Canada. The funds raised at this year’s event will help support ambitious plans for Celtic Studies at St. Mike’s,” says Lisa Gleva, St. Mike’s Executive Director of Advancement.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, an Irish-Canadian politician, Catholic spokesman, journalist, poet, and a Father of Canada’s Confederation. In acknowledgment of his legacy and the important historic and continuing contributions of the Irish in Canada, the University of St. Michael’s College has partnered with the Embassy of Ireland and Consulate General of Ireland, Toronto, to establish the St. Michael’s College Awards for Irish Heritage. Elementary and secondary school students are invited to submit projects that explore and celebrate Irish heritage in our city, province and country. The submission deadline is March 26.

Celtic spirit flourishes both inside and outside of the classroom as Celtic Studies boasts a very active and proud Course Union that hosts numerous co-curricular events centred around Celtic language, sport, food, and culture.

“We are a close-knit group—both the faculty and the students. It’s one of the advantages of being a part of a small program as you get to know your classmates and professors on a different level. We all have a fierce pride for Celtic studies and the language programs, and we promote them whenever possible to ensure people know about the crosscutting nature of the courses,” says Cameron Foley, Event Coordinator for the Celtic Studies Course Union. “We embody the Celtic craic (fun) and love the ancient cultures.”

March gives us the occasion to celebrate not only Ireland’s patron saint, but also the patron saint of Wales, St. David. On March 7, the Celtic Studies Course Union has organized festivities celebrating Welsh culture as part of St. Michael’s Culture Week. The festivities will include a supper in Macrina Hall of St. Basil’s Church with a menu featuring traditional potato and leek soup with homemade bread.

This semester, Celtic Studies Prof. Pa Sheehan began hosting pop-up gaeltacht events on a bi-weekly basis. The purpose of a gaeltacht is to allow the Irish language to become the default language at a set place and time.

“To be a speaker of Irish in Canada means making a deliberate effort to use the language as frequently as possible, which can admittedly be a challenging process at times. A pop-up gaeltacht makes this process much easier. These events normalize the use of Irish at a particular time and place. An open and welcoming space for anyone willing to use the Irish language,” says Sheehan.

Upcoming gaeltachts are scheduled for Friday, March 7 and 21 at 7 p.m. at PJ O’Brien’s Irish Pub and Restaurant.

On Friday, March 14 all are welcome to join in the céilí held in Charbonnel Lounge on at 6:30 p.m. March’s celebrations will be rounded out an Irish language movie screening hosted by the Toronto branch of Conradh na Gaeilge, a social and cultural organization that promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. A showing of Kneecap is scheduled for Friday, March 21 at 7 p.m. in AH100.

For incoming students wishing to do a deeper dive into Irish Gaelic culture, St. Michael’s will be offering a new experiential learning course for the 2025 Fall term. Students enrolled in this course will have the opportunity to travel to Ireland and be immersed in the rich culture that studying Irish language, traditional Irish singing and dancing, sport, media, drama, and contemporary Irish literature (in English and in Irish).

Learn more about our Celtic Studies program.

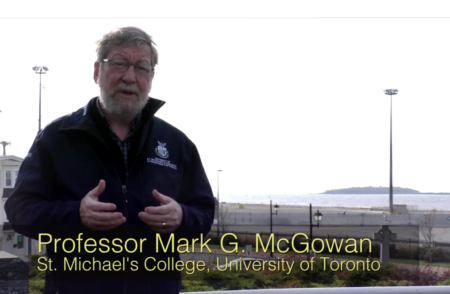

St. Mike’s congratulates Prof. Mark McGowan, an International Co-Leader (Canada), on “Historic Houses and Global Crossroads: Revisioning Two Northern Ireland Historic Houses and Estates,” which has been awarded a major research grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom for 2025-2027.

The project, which brings together scholars, communities, thinkers and econometricians from all over the world, is led by the Treaties Spaces Research Group based at the University of Birmingham (UK).

Prof. McGowan’s work is focused on Lord Dufferin, Governor General of Canada from 1872-1878, and his engagement with Indigenous issues during his tenure—the creation of the Indian Act, and government sponsorship of Indigenous Residential Schools. Dufferin was the Lord of Clandeboye House, near Bangor, County Down, and the Canadian dimensions of the project highlights the imperial/colonial connections of this estate, through its owner.

McGowan’s grant will take him to Clandeboye, the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, and the British Library. The project also highlights the research dimension of St. Mike’s Celtic Studies program, and the international presence of the program.

Learn more in this short video clip featuring Professor Joy Porter, the lead investigator.

When St. Mike’s Professor David A. Wilson completed his two-volume biography of the Irish Canadian Father of Confederation Thomas D’Arcy McGee, he was planning to continue teaching in the College’s Celtic Studies Program for the rest of his career. Instead, in 2013 he was appointed General Editor of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, and has been there ever since – while still retaining a connection with the Program.

“I love working with such a talented team of editors and translators,” he says, “and having the opportunity to bring our biographies to the widest possible audience,” he says. With over 9,000 biographies published and more coming out each week, the Dictionary is the largest bilingual project in Canadian humanities. “Drawing mainly on primary sources, our biographies range from prime ministers to public hangmen, cardinals to cult leaders, bureaucrats to bootleggers,” Wilson notes. “From the story of a young Indigenous boy who froze to death while on the run from a residential school, to that of a mentally ill woman trapped in an Asylum for the Insane, they reflect a wide variety of Canadian experiences.”

Now, thanks to a new website developed by the teams at the University of Toronto and Université Laval in Quebec and launched this July, it will be possible for even more readers and researchers to learn about the women and men who helped make the country what it is today.

“Almost all Google searches are by theme rather than by name,” Wilson explains; “by linking individual biographies to broader themes, the new website will make our biographies much more accessible. At the same time, the links enable our readers to learn more about themes related to a particular biography.” For example, if someone Googles “Enslaved Black people in the Maritimes,” they will be directed to more than 40 related biographies, can read an essay outlining their historical context, and will have access to other sources on the subject.

Individual biographies are starting to get a new look as well. More of them now begin with a 100-word summary of the entry so that readers can quickly assess their significance, and they have headings and subheadings that highlight particular sections.

Until recently, the Dictionary had been organized chronologically by death date, with the new entries focusing entirely on the 1940s. Now, half of the biographies are drawn from all periods, enabling the Dictionary to draw on new research from earlier periods and to move forward into more recent times.

“Everyone in our Toronto and Quebec offices is excited by these changes,” says Wilson. “We have much more flexibility, and can include even more biographies of Indigenous peoples, racialized minorities, women and members of the working classes.”

All the biographies are subjected to a thorough editorial process. As General Editor, Wilson is the final set of eyes, reading each piece before it is posted to the website. “By the time the biographies land on my desk,” he says, “they need very little work. This is probably the most rigorously researched dictionary of national biography in the world.”

Unlike many other biographical dictionaries, the Dictionary of Canadian Biography remains free to readers, thanks to the support of the federal government, as well as of donors. Wilson is currently engaged in a fundraising campaign to ensure the Dictionary can continue its current level of activity and its contributions to the history of Canada.

“It is such an honour to be in both the Celtic Studies Program and the Dictionary of Canadian Biography,” says Wilson, “and to contribute in different ways to the intellectual life of the country.”

You can check out the website at www.biographi.ca

The University of St. Michael’s College is delighted to announce that Dr. Eamonn McKee, Ireland’s Ambassador to Canada, has been named an honorary fellow of the University. Formal acknowledgement of the appointment will be made on Tuesday, May 28 at the opening reception for the Canada, Ireland & Transatlantic Conference, which takes place at St. Michael’s May 28-30.

“It is a privilege to offer recognition of the extraordinary friendship Ambassador McKee has shown St. Michael’s in the four years of his appointment to Canada,” says University President David Sylvester. “The local Irish community played a significant role in the founding of the College in 1852. More than 170 years on, our Celtic Studies program is a testament to those ties. We are grateful to Ambassador McKee for his ongoing support for—and involvement in—this world-renowned program.”

Honorary fellowships are awarded to individuals whose ongoing work aligns with the vision and values of the University. An honorary fellowship draws the recipient into the St. Michael’s community for mutual enrichment, inspiration and encouragement.

“I am thrilled and honoured to become an Honorary Fellow at St Michael’s,” says Ambassador McKee. “There has always been a warm welcome for me at the College. It has had a long and enriching relationship with the Embassy and indeed with all my predecessors as Ambassador.

“The College has been a source of great new friendships for me. I am indebted to Professor Mark McGowan for all his guidance as well as the corpus of his work on the Irish in Canada,” Ambassador McKee says. “He has become a great friend as we collaborate on projects like Fifty Irish Lives in Canada and the Global Irish Famine Way. President David Sylvester along with Principal Irene Morra have a great vision for the College and Irish studies are very much a part of that, I am delighted to say. I think that Irish Studies in Toronto have been served very well by St. Michael’s. There is tremendous scope for expansion and development.”

Born in Dublin, Dr. McKee was appointed in 2020 as Ambassador of Ireland to Canada, Jamaica and The Bahamas, having served previously as ambassador to Israel and South Korea. He holds a degree in modern Irish history and economics from University College Dublin and earned a doctorate from the National University of Ireland, with a thesis on Irish economic policy, 1939 to 1952.

Dr. McKee joined Ireland’s Department of Foreign Affairs in 1986. His storied career has placed him at a key juncture in modern Irish history. While stationed in Washington from 1990 to 1996, he became part of the early discussions on the Northern Irish Peace Process. He then was appointed a member of the Irish government’s team involved in the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement, which helped bring peace to Northern Ireland.

“The story of the Irish in Canada has been a revelation to me over my four years here. The influence of the Irish has been profound, their experience over the generations reflective of powerful forces at work on both sides of the Atlantic,” he says. “The range and depth of this story is barely known in Canada and virtually forgotten in Ireland. I can guarantee you that my explorations of this won’t finish when I leave in August so I’ll be a Fellow in word and deed!”

St. Michael’s Mark McGowan is a Professor of History and Celtic Studies, cross-appointed to the Department of History at the University of Toronto. Professor McGowan is renowned for his work on the Catholic Church in Canada and the Great Irish Famine, as well as the lasting impact that the Famine’s mass migration had on Canada.

The Canada, Ireland, and Transatlantic Colonialism Conference had a polygenesis of sorts. In March 2023, Ambassador Eamonn McKee held a reception at the Embassy Residence in Ottawa for the Coollattin Canadian Connection. I was invited because of my work with the project, which helps to link the former estate of Earl Fitzwilliam in Wicklow with descendants of the tenants he assisted off the estate in the 1840s and 1850s. It was there that Tom Jenkins, a Coollattin descendant– and recently Chancellor of the University of Waterloo –proposed that St. Mike’s be the hub linking Canada-Ireland research projects. This dovetailed nicely with the Ambassador’s and my plans to bring to light Ireland’s role within the British Imperial project, specifically settlement and migration to British North America. He and I already had a book project in process called 50 Irish Lives in Canada, but we both were searching for some vehicle to explore issues of migration, colonialism, and cultural transfer from Ireland to Canada. We thought of a gathering and then perhaps a publication.

Eamonn, while in discussion with President David Sylvester and Principal Irene Morra, fleshed out the idea of the University of St. Michael’s College holding a conference, perhaps as a launch pad for another idea, the creation of an Irish research centre at St. Michael’s. Both ideas seemed to have legs and had the added bonus of boosting the prominence of the College’s Celtic Studies program (which was currently under renewal and renovation). With the co-sponsorship of the Irish Embassy, and with some financial support from the Irish Cultural Society of Toronto and the University, the Ambassador and I began to map out what a conference might be called and who we might invite. The Embassy was keen to foot the bill for keynote speakers, particularly from Ireland, and I was hopeful that we might engage our newly signed Memorandum of Understanding (May 2023) with Maynooth University.

Eamonn and I hammered out the rough framework for the program and bandied about keynote speakers. Eventually, five speakers emerged, all distinguished professors in their own right: Heidi Bohaker (University of Toronto, an expert of Indigenous-Crown Treaties), Deirdre Raftery (University College Dublin, world’s leading expert on Irish women’s religious), Christopher Morash (Trinity College Dublin, an expert on Irish media and communications), S. Karly Kehoe (St.Mary’s University, an expert on Ireland and the British Empire), and Donald Harmon Akenson (Queen’s University, Canada’s Dean of Irish and Diaspora History). A call for papers yielded six panels—Indigenous/Irish engagement, Imperial Ireland, Irish Religious Diaspora, Communication & Migration, and Cultural Questions. Alas, our Maynooth contributor had to opt out because he was called to work on the Normandy D-Day commemorations this year.

The added bonus, however, was to be a special session on the Indigenous Gift to Irish Famine Relief, a topic that recently emerged out of my own research. With Jason King of the Irish Heritage Trust (Dublin) we planned a session to showcase the previously unknown donation of the Indigenous peoples of Canada to assist the Irish people during the devastating period of the Great Famine (1845-52). The IHF has been preparing a film on the subject, which will be released May 19, and the session will feature both Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe speakers, with Heidi Bohaker and myself filling in the historical details from a settler perspective. We saw this session, the lead session in the conference, as a further effort to honour St. Michael’s commitment to the TRC recommendations.

In an effort to engage both the scholarly community and the general public, we are not charging a registration fee for the conference. Often, fees are roadblocks to interested members of the broader community from participating in these events. The Indigenous Aid session will be broadcast on Zoom.

It has been quite a year, and the conference comes none too soon since Ambassador McKee’s tenure as Ireland’s representative in Canada ends this summer. I am very grateful that he has made St. Michael’s his go-to academic institution during his four-year sojourn in Canada.

Please visit the website for the Canada, Ireland and Transcolonialism Conference for the conference schedule and additional information.

Read other InsightOut posts.

The University of St. Michael’s College salutes Professor Emerita Ann Dooley, who has been named the inaugural recipient of the Ireland Funds Canada Distinguished Leadership Award.

Dooley, one of the founders of St. Michael’s Celtic Studies program, has been inspiring students and working as a tireless ambassador since the program’s inception. She was presented the award – a custom book box containing a first-edition, signed copy of works by the renowned Irish poet Seamus Heaney– at the Ireland Funds Canada’s St. Patrick’s Day luncheon, held March 8 at the Arcadian Court in Toronto. Proceeds from the event will benefit the Celtic Studies program.

In 1975, while Dooley was a graduate student at Toronto’s Centre for Medieval Studies, she was approached by Fr. John Kelly, CSB, then St. Michael’s President, and the English Department’s Prof. Robert O’Driscoll to discuss creating an introductory course in Celtic Studies.

An instant success, the class quickly led to more courses being added, with Mairin Nic Dhiarmada teaching Irish Language, and then Prof. David Wilson joining to teach history. Over the years, numerous graduate students and graduates of the program have come back to teach as sessional instructors, and you’ll find others teaching at such schools as Harvard, Trinity College Dublin, and at the National University of Ireland Galway.

The 2024 Distinguished Leadership Award was presented jointly by Oliver Murray, Chair of the Ireland Funds Canada, and long-time St. Michael’s friend Eithne Heffernan, who serves as Vice-Chair.

While the Global Ireland Funds has long honoured exceptional community members, Dooley’s award is the first time that the Ireland Funds Canada has chosen to honour a local recipient, Heffernan noted during the presentation.

Describing Dooley as “a leading light in Celtic and Mediaeval Studies,” Murray said the award was made “with great affection and appreciation for her tireless efforts supporting and promoting Celtic Studies in Toronto and Canada.”

Heffernan agreed, noting that Dooley “has spent a lifetime nurturing and educating students whom she inspired to great academic heights. She instilled in them a love of learning and of all things Irish from language to literature,” adding that she continues to be greatly loved, respected, and admired at the University by students and faculty, and by the Irish Community in Toronto.

Always generous to her colleagues, Dooley attempted to convince her program seatmates to rise with her and approach the stage to accept the award.

“It was so good of them,” Dooley says of the Ireland Funds, but she is quick to add that “the real story is the whole team, whose wonderful work is now the real story of the program, not me,” noting the ‘great contributions of Profs. Mark McGowan, David Wilson, Brent Miles, Pa Sheehan, and those who teach in the program thanks to the Ireland Canada University Foundation (ICUF).

“As many members of the local and international community know, Ann Dooley has been the defining heart and soul of the Celtic Studies program,” says St. Michael’s Principal Irene Morra. “She is, moreover, an extraordinary scholar and linguist. Her work encompasses and speaks to the breadth, rigour, and uniqueness of the program at St Michael’s College: it has ranged from Celtic mythology through to literary, cultural, and linguistic traditions from the medieval period well into the contemporary age. She is, as scholars, colleagues, and former students can attest, an absolute model of academic curiosity, knowledge, and advocacy.”

The Ireland Funds Canada has a long tradition of advancing non-political, non-sectarian, causes throughout Ireland and in Canada. The organization connects people of Irish heritage to bring positive change within Canada and Ireland, shaping culture, reconciliation, and enhancing education.

Read more on the Ireland Funds website.

For a country with a population about equal to that of the Greater Toronto Area, Ireland continues to hold a powerful fascination for people around the world, including the St. Michael’s community.

It’s a reality that Emer Maguire, who lives in Ireland’s County Louth, discovered soon after arriving at St. Mike’s as this year’s Ireland Canada University Foundation (ICUF) scholar.

The ICUF scholars have a mandate to teach the Irish language as well as to engage in various cultural events, including offering free Irish classes on a continuing education basis.

“There’s a great demand for the beginner courses,” says Maguire of the free instruction, adding that this year’s classes had to be capped at 35, and a waiting list established that stands at 50 more.

And as delighted as she is to be in Toronto sharing an appreciation for her homeland’s first official language, she says that the interest shown both by her university students and her lifelong learners will serve her well when she returns to Ireland this summer.

Having encountered some skeptics at home who question whether there’s a market for teaching Irish, she says the interest she is encountering, as well as the level of skill she’s seeing in her university students, will be good news to many.

“Some of the university students I’ve met speak a brilliant level of Irish — better than some at home,” she says, adding that Ireland’s membership in the European Union has resulted in a significant increase in the number of jobs requiring the ability to speak Irish.

Coming from a rural community, Maguire is intrigued by the sheer size of Toronto, the ease of getting around on the subway, and the number of tall buildings. But the diversity of backgrounds she sees in her classes is something she is also beginning to see in her teaching job in Ireland.

“There’s a great variety of students in my classes. Some are of Irish descent but most are from places around the world, and are simply interested in Irish culture,” she says.

At home, where she teaches primary- classes, her students, mostly Irish-born, increasingly include the children of people from Ukraine, Poland and a variety of international locations.

After a two-year sabbatical that began with a year in Massachusetts teaching as a Fulbright scholar, Maguire return home this summer, where she plans to head to the west coast of the country to teach in a Gaeltacht community, a district where Irish is the primary language in everyday use.

“It’ll be a way to get the calmness back before I return to my job,” she smiles.

Come the fall, she will be back in County Louth teaching in her local school. And while she has loved her experience in North America, she will be glad to get home to the vistas of the countryside, and to a place where she is connected to family and friends in a community small enough for almost everybody to have some form of connection.

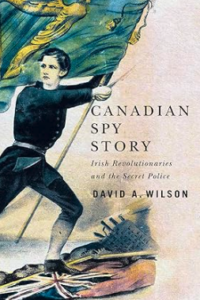

The C.P. Stacey Award Committee and the Laurier Centre for the Study of Canada (LCSC) have awarded historian David A. Wilson of the University of St. Michael’s College the 2022 C.P. Stacey Award for scholarly work in Canadian military history.

Canadian Spy Story: Irish Revolutionaries and the Secret Police (McGill-Queen’s University Press) examines the 19th-century Irish revolutionary Fenian movement and its efforts to confront British imperialism in Ireland with armed invasion and insurrection in British North America. In the years just before and after Canadian Confederation, the Fenians were seen as a significant security and military threat. In Wilson’s expert hands, the story of clandestine efforts by Canadian secret police and British authorities to infiltrate and assess Fenian networks in the U.S. and British North America make great history and great reading.

“This exceptionally well-researched book has plumbed the depths of Canadian, American and British archives, as well as dozens of 19th-century newspapers and other publications, thoroughly reconstructing how authorities responded to a revolutionary threat that aimed to strike first at Britain’s North American colonies and then a newly independent Canada,” the C.P. Stacey Award Committee noted. “The Fenian invasions of the 1860s and 1870s are widely recognized as a key factor that led to Canadian Confederation in 1867, and now the secretive efforts to gather the intelligence that gave Canadian and British governments the information needed to appreciate the defence threat posed by the Fenians have been definitively addressed.”

Wilson is a professor in the Celtic Studies program at St. Michael’s College and the Department of History at the University of Toronto, as well as general editor of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. The recipient of many awards and prizes for research and teaching, Wilson is also known for his two-volume biography of Thomas D’Arcy McGee.

Historian C.P. Stacey was brilliant in his ability to contextualize and frame military history in its contemporary political contexts. The award committee collectively found Wilson’s work mirrored this approach, remarking “Canadian Spy Story is a highly readable example of why military history has meaning and relevance for all Canadians.”

The award committee was struck by the considerable depth of choice when working to choose the winning book. There are two honorable mentions for the 2022 C.P. Stacey Award:

- Terry Copp with Alexander Maavara, produced a richly nuanced view of the First World War as experienced in one of Canada’s most diverse and complex cities in Montreal at War, 1914-1918 (University of Toronto Press). Their findings deepen, and frequently trouble, the understanding of Montreal’s place in Quebec and Canada during the war and beyond.

- Matthew Barrett, in Scandalous Conduct: Canadian Officer Courts Martial, 1915-1945 (UBC Press), provides a detailed study of Canadian officer courts martial and demonstrates how dismissal from the services had an influence on officers’ conduct, while allowing for redemption through service as other ranks.

The C.P. Stacey Award is named in honour of Charles Perry Stacey, historical officer to the Canadian Army during the Second World War and later a longtime professor of history at the University of Toronto. The award is presented annually to the best book in the field of Canadian military history, broadly defined, including the study of war and society. The award winner receives a $1,000 prize, made possible through the generous support of John and Pattie Cleghorn and family and the Department of History at Wilfrid Laurier University. The LCSC took over administration of the award in 2018 from the Canadian Committee for the History of the Second World War.

The 2022 C.P. Stacey Award Committee consisted of Kevin Spooner (Wilfrid Laurier University; director, LCSC), Isabel Campbell (Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence Headquarters, Ottawa), and Lee Windsor (University of New Brunswick). Learn more at LCSC’s War and Society research cluster.

(Source: Wilfred Laurier University press release)

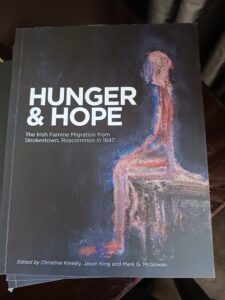

The University of St. Michael’s College offers congratulations to Dr. Mark McGowan on the release of his latest book, Hunger and Hope:The Famine Migration from Strokestown, Roscommon, in 1847 (Cork University Press & the Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University).

Hunger and Hope is the product of 10 years of research from a joint team of historians based in Ireland, the United States and Canada. As such, says McGowan, it is a work that reflects the benefits of collaboration and the potential inherent in the Memorandum of Understanding St. Michael’s signed with Maynooth University in Ireland earlier this year.

McGowan was the lead researcher and created independent studies courses for two selected teams of senior undergraduate researchers from the University of Toronto–and particularly St. Michael’s College.

These teams explored routinely generated records—e.g., census data, cemetery records, and church registers–to uncover the story of 1,490 assisted migrants from Major Denis Mahon’s estate in Central Ireland. Three in 10 migrants did not survive the voyage or the typhus epidemic that ran rampant in the sheds of Grosse Ile, Canada’s quarantine station near Quebec.

“The book tracks the migrants from the estate through their harrowing experiences in Liverpool and their transatlantic voyage on four ships of questionable quality,” McGowan says. “It then tries to examine what happened to the survivors in Canada and the United States. It is an -eight-chapter narrative that puts names, faces, and individual stories to one of the worst and much misunderstood episodes during the Great Irish Famine.”

Notes St. Michael’s Principal, Dr. Irene Morra, “This book speaks to the extraordinary historical knowledge and level of vital enquiry that Prof. McGowan continues to manifest in his publications and that he has inspired in his students in History and in the Celtic Studies program at St Michael’s College.”

St. Michael’s Principal from 2002-2011, McGowan is a historian renowned for his work on the Great Irish Famine, as well as the lasting impact the Famine’s mass migration had on Canada.

He has won multiple awards for both his teaching and writing and is also well known for his work in Catholic education, including studying the history of Catholic education in Ontario.

His lengthy list of publications includes The Waning of the Green: Catholics, the Irish and Identity in Toronto, 1887-1922, Death or Canada: The Irish Migration to Toronto, 1847, and The Imperial Irish: Canada’s Irish Catholics Fight the Great War, 1914-1918.

Cross-appointed to the University of Toronto, McGowan served as Deputy Chair of the history department (2017-19), as Senior Advisor to the Dean of Arts & Science, International (2014-17) and as Acting Vice-Provost, Students, for the University of Toronto for part of 2013.

Most recently he served as St. Michael’s Interim Principal, from July 2020-July 2022 and continues to serve the university as as professor emeritus and special advisor to the president.

A newly enhanced relationship between the University of St. Michael’s College and Ireland’s Maynooth University will further open doors for students and professors at both institutions, including new opportunities for students in the College’s undergraduate Medieaval and Celtic Studies programs, and the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology.

The agreement comes as St. Michael’s explores the possibility of establishing a research institute led by Professor Mark McGowan focused on the Irish diaspora.

A Memorandum of Understanding between the two universities, promoting technological and cultural co-operation in fields of mutual specialization, as well as in developing and deepening joint arts, humanities, theological, and information science activities, was signed in May when St. Michael’s President David Sylvester travelled to Maynooth.

His visit coincided with the annual trip to the Irish university by students from St. Michael’s Boyle Seminar in Scripts and Stories, a first-year course designed to examine the intersection between mediaeval and Celtic cultures. The timing meant Sylvester was able to witness first-hand the benefits for St. Michael’s students in accessing rare documents pertinent to the course, as well as to hear from local experts.

“This new agreement provides unique opportunities for enhanced – and new experiences for our students,” says Sylvester. “There’s great overlap between our two universities and will welcome Maynooth students, faculty, and librarians on our campus with the same degree of enthusiasm that Maynooth has welcomed ours.”

The MoU builds on an existing relationship between the two universities which includes the recognition of exchange credits, says McGowan, the former principal of St. Michael’s and a professor of History and Celtic Studies. Since both universities are working on many of the scholarly areas, it makes sense to coordinate opportunities for teaching and research, he adds.

The agreement mentions several possible paths of cooperation, including the exchange of faculty and research staff members, technicians and students; the implementation of joint research projects with common programs; providing lectures and symposia, as well as participation in congresses, colloquies, seminars; facilitating the exchange of information and academic publications; the promotion of educational activities for research personnel, technicians and students; and offering the promotion, co-operation, exchanges, and symposia for librarians and archivists.

Describing the approach of Maynooth University as “nimble and creative,” McGowan is quick to praise the university for the incredible support it has offered the Boyle Seminar since it was introduced in the 2018-2019 academic year, including arranging classroom space and lodging for both students and visiting faculty.

“Maynooth University is a reliable home base in a beautiful university town that caters to our students,” he says, noting that the safe and historic location, complete with a castle on campus, is a 20-miute train ride to Dublin.

The MoU is a notable achievement related to St. Mike’s 180 sustainability goal of “strengthening partnerships and exploring new opportunities to work with community and educational allies.”

Among the benefits of the partnership are the opportunities it offers students in the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. St. Patrick’s Pontifical University, home to Ireland’s National Seminary, is located at Maynooth, and specializes in theology, philosophy and related disciplines. Maynooth’s library has an extraordinary wealth of archival materials, McGowan explains, including the Salamanca Archive, and the university has ties to numerous other post-secondary institutions in Europe, easing the way for research.

Also benefitting from the memorandum will be the librarians of the John M. Kelly Library, he adds, noting that librarians from Maynooth came to St. Michael’s in 2018 to learn about our systems and approaches. While the pandemic intervened before our librarians could engage in a reciprocal visit, that remains as possibility, as does an ongoing exchange of library materials.

“Maynooth is the preeminent Catholic university in Ireland,” says McGowan. “It’s logical that we should be working together.”

Iain Donnelly is a second-year student of Evolutionary Biology and Celtic Studies at the University of Toronto, at least until he discovers what he wants to do with his life. He grew up in Southern Ontario and Prince Edward Island, which he still considers a second home. He is involved with the St. Michael’s Gaelic Athletic Association, and appreciates learning Irish as part of his studies. In his spare time, he enjoys skiing, is something of an avid reader, and is involved in his local Presbyterian Church.

Despite it being perhaps the most far reaching of all the saints’ feast days, most who celebrate St. Patrick’s Day know very little of who they celebrate. St. Patrick’s Day has evolved into an important celebration of identity, but it is still worth remembering the religious significance of the day, and the fascinating man that Patrick was.

Patrick was born to a well-off British family in the waning days of the Roman Empire, at the edge of a world in turmoil. The empire, which had long maintained stability in Western Europe, was crumbling as internal strife and waves of invaders whittled away at her borders. When the legions sailed from Dover for the last time in 410 A.D, they ended four centuries of Roman rule in Britain and left behind a people facing societal upheaval and the terrifying threats of invasion. This became all the more real to Patrick when, at 16, he was seized by Irish pirates and taken all the way to Ireland. To Romans, Ireland may as well have been the edge of the world. Never ruled by the empire, pagan and wholly foreign. Even the ethnonym ‘Gael’, from the Old Welsh ‘Guoidel’ (forest dwellers or wild men) reflects the ‘otherness’ of this place to the Britons. And yet it was here, of all places, where Patrick found God.

Patrick’s father had been a deacon, and his father before him a priest, but despite this Patrick was, by his own confession, not a devout man when he was taken. The pirates took Patrick to a hill called Slemish (Sliabh Mis), where he was sold to an old Druid named Milchu. There, in what is now County Antrim, Patrick was set to work tending his master’s herds of sheep. In the midst of his hardship, it was God in whom he found solace. Patrick took to daily devotion and prayer – by his account praying more than 100 times a day and night, in fierce cold and torrential rain. And so it was that after six years, God spoke to Patrick, telling him that he had done well, and that a ship was ready to take him home. Trusting in his faith, he travelled for 200 miles to the sea, only for the captain of the vessel to refuse him. Patrick retreated to pray and before long the captain relented and allowed him passage. In my favourite version, the hounds took to Patrick instantly and were distraught when he was sent away, calming only upon his return.

They sailed from Ireland and landed in Gaul, where they wandered for 28 days without food. When his companions challenged him, Patrick prayed for food, and a great herd of pigs stampeded across the path! After months of wandering, Patrick finally returned home to his family, who I’m sure had thought him long dead. I can imagine Patrick would have liked nothing more than never to think of Ireland again, but that was not to be. While furthering his study of Christianity, Patrick had a vision of a strange man named Victoricus, who gave him a letter titled ‘the voice of the Irish’. As he read, he heard voices calling out to him “We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.” And so, he did.

That is how the traditional account goes, in Patrick’s own retelling. There are a slew of accounts and stories of Patrick’s missionary work in Ireland. Patrick was not, in fact, the first to bring Christianity to Ireland; historically there were already Christian communities in the south before Patrick’s time, although he was certainly instrumental in bolstering their numbers, and founding many churches and monasteries. He did not banish the snakes from Ireland either – the Ice Age did that for him about 10,000 years earlier (nor the pagans, who persisted long after Patrick died). It is impossible to separate truth from fiction in most of Patrick’s story, nor will I attempt to, as I feel it entirely misses the point. Stories, be they true stories or truth stories, have inherent value. Patrick’s life and works can certainly teach us a great deal.

Patrick’s enslavement denied him the official Latin education that a boy of his status should have received. While his peers studied Graeco-Roman rhetoric, Patrick tended sheep. By Patrick’s own confession he was “little educated” and “ignorant”. He doesn’t make use of other texts besides the Bible in his writings, nor is he renowned for sophisticated theological arguments of the like that characterised Pelagius or Augustine. And yet Patrick’s life still inspires yearly celebration.

Patrick’s Confessio is riddled with biblical allusions, weaving his life story into the motifs of the broader Christian narrative. His six years of servitude parallels laws of captivity in the Book of Exodus, and he frames his enslavement through the lens of divine punishment for sin, and his hardship as the vehicle of his “redemption,” a very traditional Christian framework. Clearly, Patrick was exceptionally skilled at speaking to his audience, and presenting a story through language that they would understand. His time in Ireland, under the eyes of a Druid no less, would have left him intimately knowledgeable of the Irish worldview, readily able to convey the Christian message through vehicles the Irish could appreciate. The stories of Patrick describing the Trinity using a shamrock, or laying the cross upon the circular sun, or celebrating Easter through the lighting of a bonfire on Slane Hill may indeed be just stories, but these reflect Patrick’s ability, and choice to preach to the Irish at their level—something Augustine, despite all his theological brilliance, could never have done.

I do not believe that God sells people into slavery to atone for sins – a point of theology where Patrick and I may disagree. But I do think that Patrick’s suffering molded him into exactly the right person to bring Christ to Ireland. His experiences were immensely valuable in ways which he could not have foreseen. Patrick suffered because of the cruelty of his fellow men, but through his faith in God he turned that experience into something powerful.

When the legions sailed from Britain forever and the lighthouse at Dover was extinguished for the final time, many must have felt that with it the light of learning and civilization in the Isles had gone out with it. And yet the light does not go out so easily. Patrick was born into a world in turmoil and swept into it at a terrible young age. Yet Patrick took the chaos he was drowning in and found in it the tools to transform himself into a bearer of the light. I think we can do much the same.

Read other InsightOut posts

With St. Patrick’s Day nearing, popular culture is predictably filled with generic images of shamrocks and leprechauns. But when Anthony Trindle (or Antóin Ó Trinlúin, in his native Irish) reflects on the students he’s teaching in St. Mike’s Celtic Studies program, he describes them as having a complex understanding of Ireland and its enduring impact on Canada.

Trindle, who hails from Ballyphehane in Cork City, is this year’s Ireland Canada University Foundation’s (ICUF) Irish Language scholar at the University of St. Michael’s College, where his duties include teaching the only advanced-level course in Irish in Canada. When he’s not lecturing at the university, he also serves as an ICUF cultural ambassador in the broader community.

“Coming from Ireland, where everyone has to study Irish, I am now teaching students who have really gone out of their way to study the language, and who have to work hard to keep (their language skills) up,” he says. “It’s really refreshing. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study what you want to study.”

With census figures indicating one in six Canadians identifies as being of Irish descent, it’s not surprising that some students enroll in Irish language courses to do a deeper dive into their ancestry, notes Pa Sheehan, a former ICUF scholar who now is an assistant professor in St. Michael’s Celtic Studies program. Others, he and Trindle suggest, take on the challenge of learning an unfamiliar language because of an appreciation for engaging with the humanities and the resulting benefits of acquiring knowledge, even when those results gained are at a distance from day-to-day life.

But there is also a very practical reason to learn Irish, Trindle notes, and that is because the European Union’s decision to grant full status to Irish as an official language within the EU has created a new demand for Irish speakers across Europe, including in EU offices.

When Trindle is not lecturing, he can be found engaging in a variety of ICUF-related activities, including working to establish a local chapter of Conradh na Gailge, or The Gaelic League, an association of Irish speakers. Earlier this month, he organized a pop-up Gaeltacht, echoing the areas in Ireland where Irish is the primary language spoken, with more than 150 people joining the league in the first three weeks after it was launched.

His ICUF role also includes teaching a variety of levels of Irish-language classes on a more informal basis within the community, with weekly classes offering not only language instruction but also some insights into Irish life and culture.

Both Trindle and Sheehan say their knowledge of Irish has opened many doors for them, including travel, with Sheehan having taught in Newfoundland and Montana before coming to Toronto, and Trindle studying Irish at The Netherlands’ Utrecht University before coming to St. Mike’s.

“My knowledge of the Irish language brought me to Canada,” he says.

When asked how he’s finding Toronto, Trindle says he “loves it here” because both the University of Toronto and the city are very vibrant, with diversity and a lively arts landscape.

The two educators chatted recently about what Trindle has enjoyed about Toronto – and what he’s missed about home — on Sheehan’s Irish in Toronto podcast.

St. Michael’s has long been recognized for its Mediaeval Studies program, which includes an impressive history of renowned professors, rich resources, and an exciting interdisciplinary and experiential approach to learning. The program is an ideal example of the humanistic values of liberal education that reflect Catholic education at its best.

Life as a Mediaeval Studies student is not only enhanced by small class sizes and access to professors, but it is further enriched via the Mediaeval Studies Undergraduate Society (MSUS), which provides regular social and academic activities for students throughout the school year. MSUS offers academic assistance and peer mentoring within the field of medieval studies and hosts campus-wide events such medieval feasts, lectures, workshops, movie nights and a masquerade ball.

This year, the highly anticipated (and since sold out!) masquerade ball returned after a Covid-induced hiatus. Students from the Medieval Studies and Celtic Studies Undergraduate Society joined faculty and friends in Father Madden hall to celebrate a return to campus and “party like it’s 999.”

All photos by Ali Akberali are available on Flickr, and the playlist is available on Spotify.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/196462221@N02/sets/72177720305762013/

- https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7ispyXg3GlnmsTuMjKwRFe?si=90a13bda11f04179

On February 1, Prof. Pa Sheehan and students in his “Introduction to the Irish Language” class made St. Brigid’s Day crosses, to mark the feast day of Ireland’s patroness saint and the traditional Gaelic festival celebrating the beginning of Spring.

Devotees see Brigid, and the ancient Irish goddess whose name and attributes she shares, as emblematic of feminine spirituality and empowerment. Brigid’s Day is particularly significant this year since it is the first national holiday in Ireland to honour a woman.

A Brigid’s cross usually consists of rushes woven into a four-armed equilateral cross, but Sheehan’s students made crosses out of paper material as it is difficult to come across rushes at this time of year in Toronto!

The crosses are traditionally hung over doors, windows, and stables to welcome Brigid and for protection against fire, lightning, illness, and evil spirits and are generally left until St Brigid’s Day the following year.

The first day of February also celebrates the traditional Gaelic festival of Imbolc. This festival celebrates the end of winter and the beginning of spring. Consequently, it seems that St. Brigid’s Day has replaced Imbolc and is associated with new beginnings.

As the great Irish proverb says: An té nach gcuireann san earrach, ní bhainfidh san fhómhar. (The person who doesn’t sow in spring won’t reap in autumn.)

When Celtic Studies professor Pa Sheehan arrived in Toronto, he soon discovered the city’s vibrant Irish community and found that there were endless stories to tell.

Recognizing that many people would likely be interested in hearing – and sharing – these stories, he created a podcast called Irish in Toronto, a modern taken on the classic Irish oral tradition, with a focus on the experiences of Irish people living in Canada’s largest city.

New episodes of the podcast are posted every other Thursday, and topics range from the arts and sports through to academics and, of course, the immigrant experience.

“I asked myself what I would enjoy hearing about the Irish living abroad and went from there,” says Sheehan, who was born in Sixmilebridge, Co. Clare, and came to St. Mike’s to teach in 2020 after spending a year at Memorial University of Newfoundland as the Ireland Canada University Foundation Scholar. “I want to hear why they came, what made them stay, what they miss about home and whether their future will be in Canada or in Ireland.”

While the podcast’s name links it to Toronto, the subject focus will sometimes take a wider view. Recently, for example, Sheehan chatted with John Boylan, who is Deputy Head of Mission at the Irish Embassy in Ottawa.

The audience potential is as broad as the possible subject matter. Ireland is a country of about 5-million, with another 3.5-million Irish citizens living abroad, Sheehan notes, and Canadian census statistics indicate that more than 4.6-million Canadians claim full or partial Irish ancestry, with many feeling a special bond with the land of their ancestors.

And, of course, the experience of diaspora is not unique to the Irish, and so many people new to Toronto will find some common ground in Irish in Toronto, no matter who far from Ireland their homelands might be.

The current podcast grew out of an Irish language podcast Sheehan had launched in 2020, with a particular emphasis on sports and he says he hopes it will offer some information and familiarity to the Irish new to Toronto.

Sheehan, whose course offerings this year includes Introduction to the Irish Language, The Celts in the Modern World, Sport in Ireland, Traditional Music in Ireland and Scotland, and The Blasket Island Writings, says he would like to see is some of his students become involved in the podcast. He credits St. Mike’s employee and alumna Natalie Barbuzzi with creating his logo.

“I knew it had to have the CN Tower in it,” he laughs.

And Sheehan is quick to point out that he’s keen on ensuring an engaging experience, focusing on issues such as sound quality and offering a range of topics. He’s open to advice and keen to hear what people say about his project.

“I have friends giving me feedback,” he says. “I’ve been pleasantly surprised.”

Irish in Toronto is available via various digital service platforms, including Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

On May 15, 2022, at the invitation of Ireland’s Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Micheál Martin, University of St. Michael’s College Principal Mark McGowan was part of a small group commemorating the 175th Anniversary of the beginning of the Great Irish Famine.

The memorialization took place on the grounds of the National Famine Museum, Strokestown, County Roscommon, where Mark has focused his research since 2013. He served on the Historical Advisory Panel for the newly renovated museum, soon to re-open in June 2022.

Dr. McGowan is an historian renowned for his work on the Catholic Church in Canada and the Great Irish Famine, as well as the lasting impact that the Famine’s mass migration had on Canada.

He is currently doing research in the archives of the old St. Patrick’s College and the collections of All Hallows College in Maynooth, Ireland.

Photo credit: Jason King, Irish Heritage Trust.

For many in the Irish community in Toronto, the University of St. Michael’s College and St. Patrick’s Day go hand in hand. Alumni members from the 1970s and 1980s, for example, will remember legendary St. Patrick’s Day parties in the COOP that were so popular tickets sold out weeks in advance. And this year, the university is hosting an alumni reception after the St. Patrick’s Day parade on Sunday, March 20, to mark the beginning of the return to some semblance of social normalcy as COVID begins to ebb.

But the interweaving of the Irish community in Toronto and the university can be traced back to the early days of St. Michael’s, says Interim Principal Mark McGowan.

“St. Mike’s, Loretto College, and St. Joseph’s College were important institutions for the Irish community, and St. Joseph’s became a draw for Irish dignitaries as a place to give talks and to stay while visiting Toronto,” McGowan says.

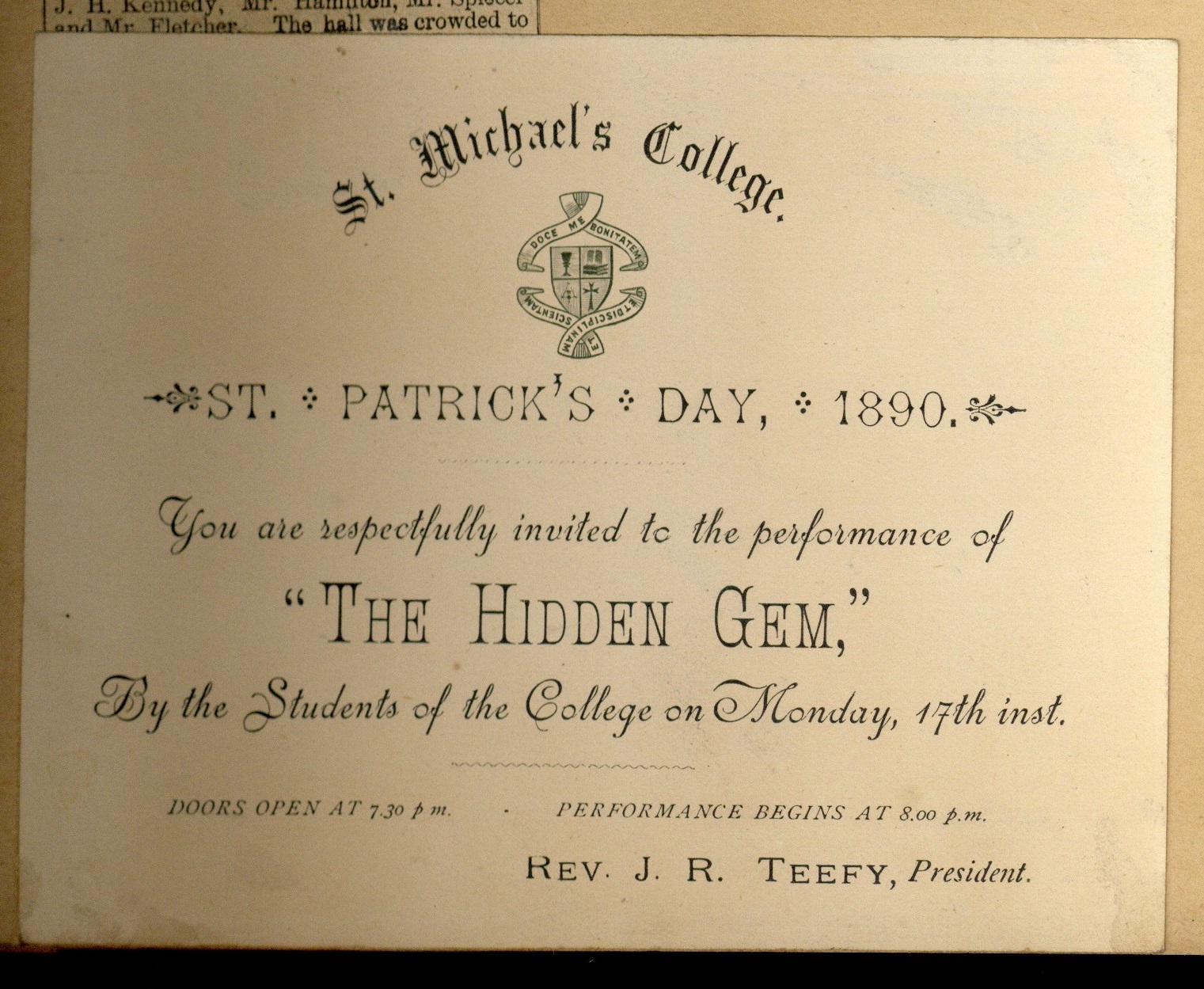

After 1877, the last year the first version of the city’s original St. Patrick’s Day parade was held, the seasonal attention turned to St. Mike’s for its annual St. Patrick’s Day concert—“pretty much the only game in town,” says McGowan, noting that attendees would then head home to private festivities.

As more and more Irish Catholics rose to prominence in Toronto—people like Francis Anglin, who was appointed to the Supreme Court, or brewer Eugene O’Keefe, who donated a substantial sum to build St. Augustine’s Seminary—it demonstrated to members of the Irish community that they could aspire to something more, and educating their children in a Catholic college became important part of that thinking, he says. St. Michael’s profile only grew within the community after it entered into federation with the University of Toronto in 1911, allowing the college to maintain control over history and philosophy classes, making St. Mike’s even more of a draw.

It was in 1975 that St. Michael’s took the first steps toward what would become the Celtic Studies program, when University President Fr. John Kelly, CSB, and English professor Dr. Robert O’Driscoll approached Dr. Ann Dooley, then doing doctoral studies at U of T’s Centre for Medieval Studies, and asked her to create an introductory course in Celtic Studies. An instant success, the course quickly led to more courses being created , with Mairin Nic Dhiarmada teaching the Irish Language, and Dr. David Wilson joining to teach history.

Over the years, numerous graduate students and graduates of the program have come back to teach as sessional instructors, and you’ll find graduates of the program and at schools such as Harvard, Trinity College Dublin, and at the National University of Ireland Galway.

Today, some students enroll in Celtic Studies courses because they are interested in learning more about family roots and Irish culture, says Pa Sheehan, who teaches in the program, but he notes that others enjoy the challenge of learning another language, one radically different from their first.

Students currently enrolled in St. Michael’s Introduction to the Irish Language class, for example, bring with them a range of first languages, including Portuguese and Japanese, Sheehan says.

Programs assistant Jean Talman, who’s been involved with Celtic Studies since 1990, recalls one former student whose parents had fled Vietnam after the end of the war enthusiastically joining the program and being billeted over one summer with a family on the west coast of Ireland, following up the next summer by staying in Wales.

While March tends to lend itself to thoughts of St. Patrick’s Day and Irish courses, Talman is quick to point out that St. Michael’s Celtic Studies program includes many courses that address Welsh and Scottish culture and literature.

“We’re a small but might bunch,” says Matilda Horton, president of the Celtic Studies Student Union, who notes that because the University of Toronto offers so many academic options, she has classmates who are linguists, or studying folklore, music or something entirely unrelated.

The student union works hard to build community, says Sheehan, who rhymes off a list of activities the students have hosted, ranging from Gaelic football to trivia nights, all open to any student so that those studying in other areas but interested in Celtic culture can participate and find people with like-minded interests.

Recently, for example, Dr. Ann Dooley offered a talk on St. Brigid’s Day, “captivating” her audience, Horton adds.

Over the years, the program has hosted some big names to speak on campus, including Irish writer Colm Tóibín and Irish poet Seamus Heaney.

“One of my favourite moments has been meeting people in class and them seeing them at a ceilidh in the COOP,” Horton says. “I realized how strong our sense of community is.”

Matilda Horton is a Victoria College student in her fourth year of her Undergraduate degree, studying Celtic Studies and Drama. She is currently working as an executive for the Celtic Studies Course Union and is in the process of applying to Celtic Studies MA courses across the UK and Ireland. Tilly would be happy to discuss all thinks Celtic Studies at any time, so long as you have a few hours to spare.

A Love for the “Curious World” of Celtic Studies

Some of the first questions asked of Celtic Studies students at the beginning of their introductory classes include: What is Celtic Studies? Who were the Celts? What makes up the Celtic identity?

As you can imagine, I was taken aback by these questions. Aren’t they supposed to tell us what Celtic Studies is? Isn’t that why we’re all here? How can I possibly know all this already?

What I didn’t realize in those first few classes was that Celtic Studies is the pursuit of answers to big questions about a relatively small part of the world. As a life-long lover of puzzles (and their clear-cut solutions), these questions both excited and terrified me. After the initial panic of being met with so many unknowns, I settled into a comfortable state of uncertainty, and this is where the real work began.

Like many of my peers, I came to the program with a genuine interest in Celtic history and identity but with little concrete knowledge. One of my best memories is being seven years old, standing on the side of the road in the north of Scotland. I remember looking around me at the vast landscape and feeling an inexplicable age and weight in the world around me. Since then, I’ve been determined to learn as much as I could about the Celtic world and its history. When I discovered that St. Michael’s offered a program in Celtic Studies, I couldn’t imagine studying anything else. Every day I am offered the opportunity to reconnect with the world that has fascinated me for so long. With every class my peers and I get to dive deeper into the history, culture and concepts that bring back that same feeling of awe in me.

With every class this curiosity is piqued and amazement grows. There is virtually no end to the things we are able to explore within the program. I have been able to delve into Celtic art, history, politics (both modern and ancient), mythology, language, literature, law, music, and so much more. My classmate are musicians, writers, historians, and artists—all of whom, like me, have found a love for the curious world of Celtic Studies. Although the program is on the smaller side, it is mighty. With a variety of student-led and department-run events (Céilí events, guest lecturers, hurling practice, film screening and even baking!) the Celtic Studies community exists vibrantly outside the classroom.

The scholarly experience in Celtic Studies is truly like no other as students have the freedom of studying under a department that is eager for us to explore. Professors challenge students to go further; to follow our inquires as far as they will go, dare to not know, and most of all keep asking questions. Because of these core values of the program, my peers and I have been able to study topics and build skills we never could have imagined (reading ancient Irish and Welsh texts), never thought ourselves capable of (learning a Celtic language!) and will have gleaned facts that will likely stick with us forever (the validity of The Wicker Man: sacrificial ritual or Nicolas Cage film? The world may never know).

I often get the question “what’s next” in my studies. People struggle to see where a degree in something so specific yet all-encompassing may lead. To that I usually have no definitive answer. Not because I have no opportunities: it’s actually quite the opposite. From my degree I have been able to explore paths I never thought possible. Maybe I will work in translations, or publishing, archives, teaching, writing, cultural studies, politics, or curation. Or maybe I will fall in love with a field of Celtic Studies I have never even considered. Ultimately, I am led by that affinity for the endless exploration that this program has instilled in me. As I apply for MA programs across the world in Celtic Studies, I do so fueled by my desire to explore and with an eagerness to see what I discover. No matter what, I will always be asking questions about the Celtic World. What next indeed.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Dr. Pa Sheehan is from Sixmilebridge in County Clare, Ireland. He was living in St. John’s, Newfoundland when the pandemic started and moved to Toronto in July. He teaches the Irish language at the University of St. Michael’s College as the Ireland Canada University Foundation (ICUF) scholar.

Finding One’s Inner Resilience

Whenever this pandemic ends and we can look at it in the past, we will all be able to say that it was a defining period in each of our lives. I want to be able to say to myself that it was the period in my life during which I realized what resilience I had always possessed but was not always sure how to use. We cannot control the end result but what we can control are the decisions we make during the process that lead us to the end result. That may sound a little contradictory but it is a perspective I have borrowed from the sporting world and adapted to use in my new normal life.

As a teenager, and even during much of my time at university, I began noticing that I enjoyed being in control of my destiny, that the final outcome would always align with my desires. We all know that this is not always the case, however. There are instances when the outcome does not correspond with the initial intentions. This used to make me feel bitter, angry, anxious and many other things. I look back at exam results with which I disagreed or at not having been picked on a particular sports team and how I allowed these external decisions make me become upset. Little did I know that these external decisions were outside of my control and that I had already done my part, so as long as I was satisfied with the role I had played, I had no reason to feel any ill sentiments.

I truly believe that this pandemic has been a blessing in disguise for me personally. I do not want to belittle the appalling circumstances in which many people find themselves due to the pandemic. I only want to acknowledge the wonderful things it has done for me and I hope you can appreciate that. I talked about resilience at the beginning of this article and I want to refer to it again.

Many moments have tested my resilience during this pandemic. I am from Ireland and have had trips home cancelled, meaning I have not seen my family in well over a year now. My job involves organizing social events and fostering a sense of community amongst the Irish themselves in Toronto as well as anyone interested in Irish culture. This has obviously been affected. One could view my moving to Toronto during the pandemic as a pity, considering I cannot experience what the big city has to offer in its fullness. I am also a sports fanatic, whether it be playing or watching and this aspect of my life has been considerably impacted as well, as sports events were cancelled one after one. I was in the middle of training for my first marathon, which inevitably succumbed to the pandemic. Having been deprived of playing my first love—the Irish sport of hurling—while living for a year in Newfoundland, I welcomed the move to Toronto as it would afford me the opportunity to play it again, given the number of Irish expatriates living in the city. Of course, the pandemic continued and these plans were scuppered along with many others.

A couple of years ago, I would have viewed these setbacks with frustration as I could do nothing to control them. However, I realize now that there is beauty in the fact that I cannot control them. It means that I must make new decisions which are within my control. For example, my inability to physically go back to Ireland has encouraged me to reach out more to people back home whom I may have neglected in the past, whether they be family or friends. It has also motivated me to appreciate the greatness of my homeplace, something I strive to illustrate each day in my teaching of Irish language and culture. Not being able to physically host social gatherings has afforded me opportunities to organize more online events and I am extremely thankful for this as I have most definitely interacted with more passionate and enthusiastic Irish people as a result of the compulsion to go online. The cancellation of marathons and hurling championships has reminded me of the reasons I initially fell in love with playing sport. I do it because it makes me feel good, simple as that. I am still running almost every day, but not because I am training for a marathon that may or may not take place in the future. I have no control over that. I train to feel well. And whenever I can play hurling again, the result of the match will not be significant, nor will the quality of my own performance. All that will matter will be the sheer enjoyment I derive from playing the game and making my best possible effort. Never in a million years would I thought I would have uttered that last sentence!

As plans continue to go awry, flights continue to be booked and cancelled, restrictions are lifted and then enforced again, events are planned only to be aborted once more, I take solace in the fact that my mind is not bound by the outcomes which I cannot affect but by the decisions which I choose to make every day to make the best of every possible situation. Resilience is something each human being possesses but only initiates when necessary. I encourage anyone to solely focus their minds on the decisions they can control. Although you have no say in them, the results will probably astonish you.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Dr. Mark McGowan is a Professor of History and Celtic Studies, and the Interim Principal of the University of St. Michael’s College for the 2020–2021 academic year. Dr. McGowan is an historian renowned for his work on the Catholic Church in Canada and the Great Irish Famine, as well as the lasting impact that the Famine’s mass migration had on Canada.

Explore other InsightOut posts.

Introduced in the 2018-2019 academic year, the Boyle Seminar in Scripts and Stories is a unique offering for first-year students interested in the transmission of knowledge and preservation of intellectual culture during the medieval era. As one of three SMC One seminars at St. Michael’s, the Boyle Seminar brings together the strengths of two St. Michael’s-sponsored programs – Medieval Studies and Celtic Studies – to give participants an interdisciplinary foundation for future academic work, preparation for careers in a wide range of fields and an opportunity to go on an international learning experience in Ireland.

Assistant professors Máirtín Coilféir and Alison More seek to give new students experience in manuscript studies, history and the Latin and Irish languages, but the program also serves as an effective bridge to university-level academic work more generally. Open to around 20 students each year, the small class size of the Boyle Seminar helps each cohort to bond into a tight-knit group, and gives each student one-on-one time with both professors.

A Hands-On Approach

Professor Coilféir, who teaches in the Celtic Studies program, describes one of the primary themes of the course as “the practical application of theoretical knowledge.” Instead of giving students a dry survey of medieval and Irish culture, he and professor More give students direct experiences of the practices that monks used centuries ago to create and preserve manuscripts, which are the hand-written copies of documents prepared in the medieval scriptorium.

By encountering parchment first as a dried and treated animal hide, students begin to see the living material basis for history. “We spend quite a lot of time talking about ‘how do we go from cow to page?’” Coilféir says. Practical experience with parchment, ink and feather quills, which the students cut into usable pen nibs, helps to reinforce the notion of medieval and Celtic culture as representing a living history – one that students are equipped to take up with gusto.

Most Medieval Studies programs for undergraduates follow a very different and far more traditional pattern than that of the Boyle Seminar at St. Michael’s. Professor More, a medievalist, describes the typical progression for an academic in her field as requiring at least three years of dry study before a typical student gets a chance to see or touch a manuscript.

By contrast, the Boyle Seminar puts centuries-old manuscripts in the hands of students during their first months at university. This fearless and practical approach to the artifacts of the period gives students a solid basis for “manuscript studies and the often-baffling sources of medieval history,” More says, as well as training that can serve as effective preparation in a variety of other fields such as law, theology and cultural conservation.

The May trip to Ireland reinforces the practical emphasis of the course, with visits to ancient cultural sites including an active archaeological dig at the Blackfriary Archaeology Field School. Though not for academic credit, the trip gives students an opportunity to handle artifacts fresh out of the ground and learn contemporary archaeological methods.

A St. Michael’s Tradition

With both the Pontifical Institute of Medieaval Studies (PIMS) and the John M. Kelly Library located right on campus at St. Michael’s, it only makes sense for the Boyle Seminar to rely on the research institute and library’s holdings to give students access to special texts for the course.

One of the seminar’s key texts is Integral Paleography, a collection of articles about different scholarly approaches to medieval writing. This book has a special connection to the seminar: it is the work of Fr. Leonard Boyle, OP, the scholar and former PIMS professor for whom the seminar is named.

Fr. Boyle was an important figure at PIMS and helped to build the University of Toronto’s Medieval Studies program, now hosted at St. Michael’s. In 1984, Fr. Boyle left Toronto for Rome after Pope John Paul II appointed him Prefect of the Vatican Library. There, the scholar-priest worked for years to expand access to the library’s holdings to scholars around the world. In so doing, he changed the reputation of an institution “not well known for its hospitality to visitors” into a place where “the doors were flung open from morn till night,” as Nicolas Barker wrote in his obituary for Fr. Boyle for The Independent.

The spirit that animated Fr. Boyle’s approach to the Vatican Library – prioritizing access for everyone who needs it – continues to animate the Boyle Seminar. In line with a storied history of scholar-teachers at St. Michael’s, professors More and Coilféir open up a world of ideas and experiences while helping students to make lateral connections across disciplines. Rejecting the Ivory Tower model of the academic enterprise in favor of a robust commitment to the liberal arts, the seminar’s approach fuels creativity and courage in first-year students’ approaches to their academic careers and later readiness for the workplace. As one student observed, “when you think about the past, you think more about the future.”