Stephen Tardif is a Professor in the Christianity & Culture Program at the University of St. Michael’s College. He also offers courses in the & Studies Program. Recently, Dr. Tardif was named as co-editor of The Hopkins Quarterly, an international journal of critical, scholarly, and appreciative responses to the life and work of Gerard M. Hopkins, S.J., as well as to those of his circle.

The annual Langan Lecture takes place Tuesday, September 19 at 6 p.m. in Charbonnel Lounge.

One disappeared in the dead of winter; the other at summer’s height. The loss of a pair of mentors in the space of a year brought to mind Oscar Wilde’s quip, in The Importance of Being Earnest, that losing one parent might be a misfortune, but losing both looks like carelessness. In this case, the joke has a strange and plangent charm, for a kind of carelessness did characterize my attitudes to Dr. Janine Langan and Sr. Frances McKenna. In retrospect, the assurance of the enduring presence of these former teachers in my life was like an unconscious dependence on an uncounted blessing, a reliance on graces taken for granted until they were gone.

* * *

The word “mentor” is actually an eponym, one derived from a character in Homer who serves a function closely connected to its modern-day meaning (while also echoing Greek etymological roots associated with mind, memory, and thinking). In The Odyssey, Mentor is introduced as a lieutenant, a placeholder for Odysseus, the long-absent hero, who has been entrusted with the administration of his household. Immediately following his introduction, however, this character’s form becomes the disguise that Athena uses to guide Odysseus’ son, Telemachus, in his initial sojourn. Thus does the ancient poem disclose a deep phenomenological reality: in enabling us to find our paths in life, mentors often seem, to us, like gods in disguise.

Janine Langan, who died in December of 2021, was just such a guide. In the winter term of my first year of undergraduate studies, I took what was to be her final course as an instructor of record at St. Michael’s College; even now, I find it difficult to convey the transformative effect of this single, half-credit class. “Christian Symbols II” was, ostensibly, a survey of responses to the Book of Job. For me, though, it served other functions. Taken simply as an itinerary of reading, the course provided a bracing introduction to figures who would exert considerable influence over the rest of my undergraduate studies; the syllabus featured theological and philosophical luminaries of the Catholic intellectual tradition in the 20th-century. To read Hans Urs von Balthasar, Simone Weil, René Girard, and Jean-Luc Marion as a first-year student was to be given a map, a cartographic sketch of the night-sky’s constellations that identified fixed stars by which to navigate at the very beginning of my own intellectual odyssey.

This course was also my introduction to Christianity & Culture, the program which Janine Langan co-founded and in which I now have the great privilege to teach. In subsequent years, I would become familiar with professional literary criticism—its history, its scope, and its norms; in this class, however, I witnessed a virtuosic version of this practice that broached what I would later recognize as long-established boundaries. I have never forgotten this early encounter with the tools of my future discipline being turned towards such thrilling, unconventional ends. Instead of training our focus either on text or context—on the beauty of aesthetic objects or on the truth of social realities—our attention was fixed elsewhere. We were taught to see, in the figures we met from week to week, the beauty of personality. Whether brooding on Job and the nature of evil or offering their own arduously acquired insights into human suffering, the authors we encountered gave vivid glimpses of achieved selves. And, in doing so, they became so many conduits of intellectual, artistic, and actual grace.

“Christianity and Culture” is T.S. Eliot’s title, but the phrase itself appears nowhere in the pair of essays that he gathers in that volume. The special charism of the program which now takes this phrase as its name is the exploration of the connections of its pair of terms as they are revealed through the “living stones” (1 Pt 2:5) of the Church and their stories. As they conform themselves to Christ, the figures whom we study in C&C display, in their lives and works, delicate contours which would have been impossible to fashion without the drama, the pathos, and the hope that the call of the Gospel awakens in a human life.

It was hardly a surprise to find, in the excerpts of Janine Langan’s own retrospective on her 37 years of teaching, which were shared by her family at her wake, the perfect articulation of this approach; the Church, in her courses, emerged not as a lifeless collection of exempla, the members of a diverse nation, or even the contributors to a great conversation, a tradition, or a body of knowledge. The Church, instead, was, as she put it, “a sea of radiant faces: Minucius Felix, Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine, Benedict, Cuthbert, Sir Thomas More, Teresa of Avila, Francis de Sales, Vincent de Paul, Pascal, Hopkins, Edith Stein, Dorothy Day, thousands more…and us.”

This last point deserves special emphasis: Janine Langan was a vital, vibrant, and iridescent member of the Church; she showed, in her own person, the incredible flourishing which the pregnant word, “vocation,” always promises. A partial list of the activities that this retired octogenarian would undertake in her final years would include: introducing her high school students to figures like Boethius, Dostoevsky, and St John Paul II; reading the latest philosophical doorstopper, and convening meetings to discuss it; bringing Christ in the Eucharist to invalids and shut-ins; offering impeccable hospitality to an impossibly wide array of guests and friends; and being the doting, attentive, and inspiring matriarch of a large and beautiful family.

Long before Janine’s untimely passing in December of 2021, I had pasted on my wall an ebullient and encouraging message from her which conveyed, at once, her confidence in my career, her pride in my achievement, and an affection which was volcanic, unconditional, and utterly characteristic. It was one of the joys of my life to remain in regular contact with her during what turned out to be her last years, and I’m delighted now to count members of her family as my friends.

* * *

Sister Frances McKenna, Faithful Companion of Jesus (or FCJ), died eight months after Janine Langan in August of 2022; I was also honored to have kept in contact with this beloved high school English teacher for two decades—although the pandemic had limited our last interactions to chats on the phone.

What does a mentor look like? In the case of Sister Frances, her appearance, before and after her retirement, was invariable: a floral print dress, a blue blazer (to be held, in meditative moments, by its lapels), Velcro-strapped sandals, and a plain silver cross. In teaching and in conversation, her hands would habitually assume almost theatrical poses, with her fully extended fingers recalling a conjuring magician or an impressive impresario. These gesticulations would often accompany the silent, anticipatory pauses which would precede the delivery of a delicious description. Our bad behavior, for example, would be disparaged—and yet quietly dignified—by being called “obstreperous.” A true lover of language, she would bestow, even upon her own searches for words, exotic epithets; her deliberations would sometimes occasion a “paroxysm”; at other times, they would merely “flummox” her. In all of these moments, I osmotically absorbed her linguaphilia, receiving—to the enduring chagrin of my students!—a love for rare and florid mots justes, sesquipedalian though they be.

But a shameless affection for the neglected treasures of the thesaurus was only one of the gifts that Sister Frances imparted to me. The greatest, and the most enduring, was Gerard Manley Hopkins, SJ. When I entered her classes late in my high school career, I had already acquired a love of poetry: I had been overwhelmed by an initial encounter with William Shakespeare and charmed by the slick style of Alexander Pope. In her own classes, I was awed by Wordsworth, and the inscrutable power of phrases made mysterious by the sheer confidence with which they conveyed his convictions about reality’s inner life. The discovery of Hopkins was different: here was a voice whose beauty was simultaneously bold and bewildering, enigmatic and clear. I remember brooding with pleasure and perplexity over the first quatrain of the sonnet which takes its name from its opening half-line:

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

The orchestral effect of Hopkins’ effortless organization of consonant- and vowel-sounds awakened in me an urge to explain his magnificent, microcosmic soundscapes. His poems were objects I couldn’t understand, but from whose spell I couldn’t escape. This first encounter was especially transformative not only because Hopkins continues to reveal, even now, qualities, potentialities, and felicities that I would never have imagined that the English language could possess; it was also transformative for being a sheer gift. Sister Frances commended Hopkins—a poet I had never read—to me directly; the potential affinity that she detected in me was an inspiration and, to her great credit, the poet has become, for me, a lifelong love.

I received another great gift in Sister Frances’ classroom, too. In Hamlet, Shakespeare’s prince asks a self-reproachful question in seeing an actor within the play moved to tears by a monologue: “What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,/ That he should weep for her?” The affecting story about a mourning Trojan queen is what elicits this response—and it, in turn, allows the prince to reflect on his own famous inaction. I had a similar moment of self-reflection in reading, with Sister Frances, another Shakespeare play. As King Lear’s tragedy comes to its conclusion, the main character, cradling the dead body of his faithful daughter, creates what, in a play set in ancient Britain, is a pre-Christian anticipation of the pietà. I will never forget that, while reading this scene in class, Sister Frances wept. It was an uncanny experience. In a moment, I came to the sudden realization that literature was not an arena in which to be clever, nor was it simply the repository of the human imagination’s most glorious creations—great plots and fine language. No, there was something foreign, sacred, and utterly mysterious in this “subject,” something unspeakably precious whose reception depended on one’s own sensitivity, something which I had not yet received or even recognized. Much later, I would connect what I had witnessed in that classroom with an event in Hopkins’ own life: I came to see the tears that the poet shed while composing his ode, “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” as what he would have understood as a “consolation” in the Ignatian tradition. For Hopkins and for Sister Frances, literature was an occasion for “the gift of tears.”

Sister Frances was also a truly wonderful teacher. Tolerant of our mischief and undaunted by our diffidence, she was unfailingly, even heroically, “gracious”—a word and a quality she prized above all others. She showed her characteristic grace in poring over our middling essays; in elucidating for us the dramatic structures of Sophocles; and simply in her insistence that we pause, in our reading, to give attention to insightful, masterful phrases, such as one from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: “We live in a flicker.”

In keeping in touch with her in the years following my graduation, I would often remind Sister Frances of this phrase, especially since her final years must have felt like anything but a flicker. Failing eyes, aching bones, and many other painful, frightful ailments turned her retirement into something other than the easy rest she so richly deserved. The end of her life became, instead, a final opportunity to display the graciousness which she so cherished, and which she displayed in such an exemplary way. In the face of agony, debility, and encroaching darkness brought on by macular degeneration—a particularly heavy hardship for such a devoted lover of the written word—she was patient, courageous, and even cheerful. In her retirement community, where, of course, she quickly came to be sincerely loved, she lived out what she called “an apostolate of friendship,” becoming for lonely souls what she had always been for Christ in her life as a religious: a faithful companion. When news of her sudden passing reached me during a term of teaching overseas, I was sad for myself but relieved on the occasion of her release from further suffering; I later learned that she had died with the words of St Augustine on her lips: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.”

* * *

To begin these reflections, I borrowed from the first, disarming verse of W.H. Auden’s elegy, “In Memory of W.B. Yeats”:

He disappeared in the dead of winter:

The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted,

And snow disfigured the public statues;

The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day.

What instruments we have agree

The day of his death was a dark cold day.

Auden begins his poem with the seemingly indisputable fact of the Irish poet’s disappearance; but he does so precisely because Yeats does not vanish, and instead enters into history through his body of work. By emphasizing this fact, Auden connects with a long tradition which finds, in the endurance of a poet’s posthumously repeated and remembered words, a kind of immortality. Indeed, the “resurrection” which Yeats achieves in the poem (one attained in keeping with an ancient elegiac convention) is precisely an afterlife in art. But Auden has a fine sense for the ambivalence of this consolation. Although Yeats may enjoy a godlike status in living on, in some form, in his body of work, it comes at a cost: the sparagmos, that violent dispersal of body parts which the victims of ancient Greek tragedies endured:

Now he is scattered among a hundred cities

And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections,

To find his happiness in another kind of wood

And be punished under a foreign code of conscience.

The words of a dead man

Are modified in the guts of the living.

If the afterlife of a teacher is less obvious, it is also less ambiguous. The depth of gratitude that I feel for my teachers is hardly unique; I can remember many of the anecdotes they themselves shared with me about the pivotal pedagogues in their own lives. In this way, the continuum of gift-transmission which we call “tradition” continues, perpetuated from generation to generation as student follow in the footsteps of the teachers who transformed their lives. St. Paul tells the Corinthians that he “received from the Lord what [he] also delivered [to them]” (1 Cor 11:23), reminding them that the gifts they have been given also impose a solemn charge to bear them, to live them fully, and to pass them on to others. This exhortation exquisitely captures the joyful burden of having had incredible teachers: while the standard they set is imposing, the energy their memory imparts inspires our own endless attempts to emulate their example.

I am constantly thinking of Sister Frances when I facilitate, for my students, the same unforgettable introductions I was so blessed to receive through her. Janine Langan is an even more proximate presence in my life at St Michael’s College, where I’m humbled by the opportunity to continue, in a small way, her institutional legacy in Christianity & Culture, an academic program which remains such a gift to me and to so many others as well. Both of these now-departed mentors continue to show me what it means to live out one’s vocation. A laywoman and a religious, they were each witnesses to the Catholic Church—witnesses who lived out the calls to service that they has received and which, in the Church, they each so beautifully fulfilled.

But as members of the Church, these women are not, to me, pious, fading memories, venerated with warmth even as they slip, year after year, imperceptibly but inescapably, into the gentle, obliterating mists of the past. They are dead—but the dead shall be raised. In the meantime, they are in my prayers and hope that I may always remain in theirs and benefit from their powerful intercession. And, after a time, I hope to realize that beautiful wish which St Thomas More expressed in a letter to his family, shortly before a temporary separation was imposed upon their communal life: “May we one day meet merrily in heaven.”

Read other InsightOut posts

Interested in the ongoing work of Truth and Reconciliation in Canada? Wondering about the role and responses of Christian Churches in relation to settler colonialism and the Indian Residential School System? First year, and now upper-year students are invited to explore the complex relations of Christianity and Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island in the Fall 2023 seminar, “Christianity, Truth and Reconciliation”– SMC185 for first-year students, CHC300 for upper-year students. The course incorporates small seminar-style discussions, personal reflection and an experiential learning opportunity at the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre in Sault Ste Marie during the fall reading week.

For more information, please see the article, “A Rare and Deeply Impactful Experience” or watch this video on the course.

First-year students can enroll in SMC185H1F and upper-year students can enroll in CHC300H1F. The courses will occur simultaneously on Wednesday 11:00am – 1:00pm. Students who are interested or have any questions can reach out to smc.programs@utoronto.ca

On first glance, a doctoral student, a university administrator, a lawyer, and a high school teacher might not have a great deal in common on a day-to-day basis. But four alumni who came together recently to talk about life after graduating from the Christianity & Culture program at the University of St. Michael’s College were bound together by their respect for the program, as well as for the people teaching in it, noting that their studies gave them a unique lens through which to view the world.

An added dimension to the alumni panel, held in the Basilian Fathers Common Room, was the fact that three of the four participants went on to advanced theological studies, and so attendees were given a great idea of how C & C meshes with further theological studies, as well as what to expect at the graduate level.

Alumna Therese Hassan, for example, credits her time in both the Christianity and Culture program and St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology, where she earned a Master of Theological Studies degree, with helping prepare her more effectively to meet the needs of the secondary students she teaches today.

“Our students yearn for a connection to their faith and not every teacher they encounter has had the experience that I’ve had,” Hassan, who teaches for the Dufferin Peel Catholic School Board.

She describes her time at St. Mike’s as “super valuable,” allowing her students to have a different experience in her class because she is able to speak with confidence about topics such as the teachings of the Catholic Church and sensitive moral issues.

“My theology degree allowed me to grow and build on what I had learned in Christianity & Culture by taking a more in-depth look. And while my C & C classes were small and allowed me to participate, my theology classes were even smaller. I am confident that when my students tell me they have a different experience in my classes it is due to my own academic experience,” Hassan says. “Theology courses were so in-depth that they really allowed me to grow.”

Patrick Nolin, a graduate of the Christianity & Culture program now engaged in doctoral studies at Regis College also cites small classes as helping him become more involved in his classes – an area of study, incidentally, in which he had never intended to become so engaged.

“I didn’t know I’d join C & C because I was into history in high school and that was my planned major but then I took a first-year seminar course on Catholicism and that was it, hook, line, and sinker,” he laughs.

One of the aspects of the program he really appreciated was how its interdisciplinary nature helped create new lines of study, noting, for example, the growth in eco-theology that has taken place since the days he first encountered the subject area in his undergraduate years.

“Christianity & Culture taught me to figure out what questions that need to be asked,” he said, adding he often uses the transferable skills gained in his undergraduate years. Communicating to a small group, for example, has been a help both the past work in sales and his current life as a doctoral student.

Panelist Andrea Nicole Carandang found herself unable to imagine the experience of many of her university peers, who spoke of impersonal classes of 300 students, given the seminar-like size of many of her C & C classes. There, she found the ability to enter into conversations with her professors and her peers, allowing her to gain the confidence to debate respectfully and to tackle life’s most challenging questions.

She recalls, for example, that in 2015 when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report came out, she was struck by an awareness that, “My faith was big part of the residential school system,” she says.

But she adds, as she delved deeper into the impact of the TRC report she comfort in a lesson she says she had learned again and again as a C & C student.

“It’s not wrong to ask hard questions,” she says.

Carandang, who returned to Toronto to work on a Master of Divinity degree at Regis College, says she often uses the skills and experiences gathered in her student years in many ways in her current role as Administrative Assistant in the office of the President of Regis College, from the practical work of doing research through to brainstorming to resolve numerous challenges that arise.

C & C grad Adam Giancola, who is now a lawyer, says “education is for life,” adding that an interest in canon law from his C & C days, for example, was one of the factors that played into his decision to go to law school.

He deeply values the time taken in his C & C classes to study what the church has proposed about issues over the centuries.

“It’s a program of looking at human issues and I do this every day,” says Giancola, who has worked for Ontario’s Office of the Children’s Lawyer as well as the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee, offices designed to protect the legal, personal, and financial interests of people who face potential vulnerabilities at the hands of others.

Today, Giancola works in private practice but often engages on matters involving children and other vulnerable clients.

Thanks in part to his Christianity & Culture studies, he says he has learned to “look at people with charity and mercy. I exercise prudence and judgment. Christianity & Culture prepared me for life.”

(Above photo L-R: St. Mike’s alumni: Andrea Carandang, Patrick Nolan, Adam Giancola, Therese Hassan and RSM Theology Recruitment and Enrolment Officer Erica Figueiredo.)

For more information about St. Mike’s Christianity & Culture program, including queries about enrollment and completion, contact smc.programs@utoronto.ca.

For information about Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology programs, email inquiry.usmctheology@utoronto.ca.

Fiona Li is a proud alumna of St. Michael’s Christianity & Culture program as well as of the University of St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology (MTS 2015; ThM 2018). She is now a PhD candidate at Regis College and Associate Director of the Fraser Centre for Practical Theology. Her dissertation seeks to propose an inculturated understanding of Mary for Canadian-born-Chinese Roman Catholic women, such as herself.

In celebration of Women’s Day on March 8, the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology (RSM) will be hosting a Liturgy of the Word in remembrance of Dr. Ellen Leonard, CSJ. Sr. Ellen was one of the first women to study theology in Canada and taught for many years at the University of St. Michael’s College Faculty of Theology. She taught courses on Roman Catholic Modernism, feminist theology, and ecological Christology. She also founded the Catholic Network for Women’s Equality (CNWE), which continues to work towards “justice and equality for women in the Catholic Church and in the world.”

Along with Sr. Ellen, we also say goodbye and thank you to other female pioneers in theology who walked so we can run: Sr. Margaret Brennan IHM, the first female theology professor at Regis College; Margaret O’Gara; Rosemary Radford Ruether; Delores Williams, Sallie McFague; Mary Daly; and many others.

In remembering the past, we are also given the chance to imagine the future. Since this is the first official year of the RSM federation, it is the perfect time for all those involved—students, staff, faculty, and alumni—to dialogue with one another regarding what they envision the future of RSM to look like.

Like many students, faculty, and staff, my hope for RSM is that it not only survives but thrives; that it becomes a beacon of light and hope for theology. What this means, especially in a city like Toronto, is that RSM will need to speak to the contemporary and systemic issues in society. RSM is situated in a very advantageous position, both within Canada and, more specifically, in the city. Toronto is one of the most culturally diverse cities. With many first- and second-generation Canadians calling Toronto home, RSM is in a privileged position theologically to speak on topics that emerge from the encounters between different cultures and religions with one another. For example, with a great number of Catholics identifying with non-Western cultures and countries of origin, the Western normative systems of thinking about God and theology will need to be renegotiated. And what does it mean to be a Catholic in a multi-religious society such as Toronto? Moreover, as Toronto is home to many persons of colour, RSM is also constantly reminded of intersectionality. RSM can become a leader in decolonizing theology and thinking of theology intersectionally: how does theology written by white males affect persons of colour differently than their white peers? How has the traditional mainstream theology been used to subjugate vulnerable groups of people in society?

To this point, my second hope for RSM is that there will be more women of colour in the student, staff, and faculty populations. By appealing to and preparing women of colour for ministry or further theological studies, RSM will be providing the Toronto Church with competent workers for the harvest. But it is not enough to have women of colour in the student population. It is also important to have representation in the faculty population. Out of all the listed faculty members at the Toronto School of Theology, there are approximately eight women of colour, and only three are regular faculty members. Representation matters because it visually demonstrates to the female students of colour that they belong in academia; that their voices and experiences matter in Theology. As one of the groups that have been historically marginalized due to intersecting systems of power, women of colour have much to contribute to discussions of faith and how Theology can be reclaimed to help and empower people in vulnerable positions.

I think–especially in celebration of International Women’s Day– it is proper to say that the future for RSM is women of colour, along with other marginalized groups, with male and white women’s voices as allies. May we, those who identify as women and in Theology, follow in the legacy of all the women who have come before us, and run, so that those who follow us can walk.

The March 8 Liturgy of the Word takes place at 1:30 in chapel in the Cardinal Flahiff Basilian Centre at 81 St. Joseph St., Toronto.

Read other InsightOut posts

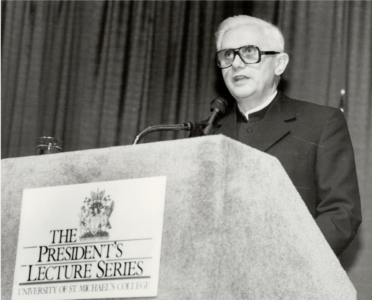

As the world reflects on the life and legacy of Pope Benedict XVI, Fr. Daniel Donovan, Professor Emeritus in St. Michael’s Christianity & Culture program, holds memories of encounters with the man both as an academic influence and as a visitor to campus in 1986.

As a graduate student at Rome’s Pontifical Biblical Institute in the early 1960s, studying how the language of priesthood came to be applied to what is known as presbyter or elder in the New Testament, Donovan had the opportunity to meet with Fr. Joseph Ratzinger, then in Rome to participate in the Second Vatican Council.

Over ice cream in an outdoor café, Ratzinger advised Donovan to work on his doctorate in Germany, home to many of the brightest young theologians, men like Walter Kasper, and Johann Baptist Metz, professors who were rising to prominence for their work in post-war Germany.

Following Ratzinger’s advice, Donovan began his doctorate at the University of Münster, where his courses included a Ratzinger seminar on Dei verbum, the Vatican II document that looked at divine revelation, a work that involved contributions from Ratzinger.

“He was warm, welcoming and kind,” Donovan says of the man who was to become Pope Benedict XVI, recalling a few invitations to lunch at Ratzinger’s home. “He was helpful to people.”

He notes that Ratzinger was very young to be a professor (Ratzinger was 31 when he was appointed a professor in 1958), a reflection both of his intellect and also of the impact of World War II on the academy, which resulted in a gap that helped bring a new school of thought to the foreground.

As for Ratzinger’s reputation for conservatism, Donovan notes that as a participant in the Second Vatican Council, Ratzinger witnessed interpretive extremes on both ends of the spectrum, and thus remained concerned that a desire to be relevant not overshadow centuries of Church teaching.

Donovan and Ratzinger met again in 1986, when Ratzinger, by now Cardinal Ratzinger and Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican dicastery responsible for ensuring a correct interpretation of Church doctrine, came to Toronto at the invitation of St. Michael’s to deliver the President’s Lecture, a talk entitled “The Church as an Essential Dimension of Theology.” His visit included concelebrating Mass at St. Basil’s with Gerald Emmett Cardinal Carter, George Bernard Cardinal Flahiff, CSB, Fr. James McConica, CSB, then president of St. Michael’s, and other priests in St. Basil’s Church.

Because of Ratzinger’s fame, he delivered his address in the old Varsity Arena, just south of Varsity Arena, to accommodate the crowds, with busloads of people arriving from as far away as Rochester, New York, Donovan recalls. Donovan then chaired a spirited in camera session at St. Michael’s open to members of the Toronto School of Theology, a session participants no doubt remember to this day.

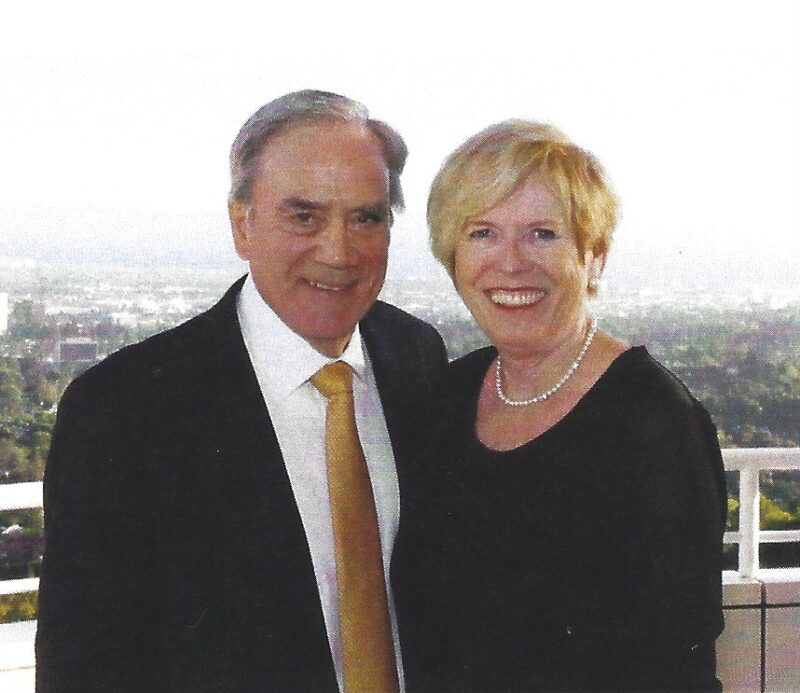

The creation of the new W. J. Bennett Family Chair of Christianity and the Arts builds on a family’s connections to the St. Michael’s community that date back decades.

The chair has been generously funded by alumnus John Bennett (SMC 6T7), expanding upon an original bequest from his father W. J. (Bill) Bennett’s estate in 1996. John has long been an active member of the St. Michael’s community, including serving as a member of the St. Michael’s Foundation, which promotes and encourages education at St. Michael’s College, acting as Collegium Chair and now a board member, and chairing the most recent Presidential Search Committee. John is also a member of the board of the Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies and was actively involved in the Regis-St. Michael’s federation .

Like his son, Bill was also very active in the St. Michael’s community, graduating with a degree in philosophy in 1934, going on to a very distinguished career in government and business. While a student, he was active in the choir and dramatics, and was a member of the Senior Literary Society. Maintaining close family ties to the Basilian Fathers, Bennett Sr. was instrumental in establishing the Michaelmas conference, an annual weekend bringing academics, politicians, business and community leaders to campus to discuss important matters of the day. He received an honorary degree from the University of Toronto in 1955.

“St. Michael’s remained an important part of my father’s life,” says John, who notes that his father’s bequest to the university funded various projects on a one-off basis within the Christianity and Culture program over the years. John’s additional funding will create a permanent chair with a mission to examine the integration of Christianity with arts and culture.

“Religious education was very important to my father and it’s more important than ever. He would be very pleased with funding a professorship in an area he valued so much,” John says. “I’m delighted to help revitalize this program because Christianity and Culture is so relevant today, and there are very few good programs now available to students.”

The inaugural holder of the Chair will be Dr. Michael O’Connor, an Associate Professor who teaches in both the Christianity and Culture and the Book and Media Studies programs at St. Michael’s College. Dr. O’Connor, who has taught at St. Michael’s since 2005, formerly served as Warden of the Royal School of Church Music, UK, and Lecturer in Theology, Ushaw College, UK. He holds degrees from Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome (STB, STL) and Oxford, Oriel College (DPhil). His research interests include music and liturgy, early modern intellectual history (especially Renaissance Rome), Christianity and the arts, and history of biblical exegesis. Recent courses have included “Ritual and Worship,” “Christianity and the Arts”, and the First Year Foundations Seminar “The Sistine Chapel: History, Image, Use.” He has also served as a board member of the Society for Christian Scholarship in Music and of the Royal School of Church Music, Canada. Outside of pandemic times, Dr. O’Connor is active as a choral conductor, composer, arranger, and music editor.

“I am honoured to be the first to hold this chair and grateful to the Bennett Family and the University for this wonderful opportunity. Our campus is home to outstanding resources in Christianity and the Arts and creative colleagues working in related fields. This appointment provides energizing encouragement to my work,” O’Connor says.

St. Michael’s Interim Principal Mark McGowan offers praise for the selection of O’Connor for the Bennett Chair.

“Michael O’Connor is a long-standing member of Christianity and Culture and has made significant contributions as an outstanding teacher, insightful researcher, and accomplished musician,” says McGowan. “He is an internationally recognized expert on liturgical music and a popular contributor to many co-curricular activities.”

University President David Sylvester agrees.

“Dr. O’Connor is a highly respected member of the St. Michael’s faculty whose work reflects St. Michael’s mission to build a transformational faith and learning community committed to the rigorous search for truth and meaning,” says Dr. Sylvester. “The creation of the Bennett Chair will further enrich the Christianity and Culture program, allowing it to serve not only our students but also the broader community in new and creative ways. We are grateful to John and his family for their decades of generosity and support.”

John has had a long and distinguished entrepreneurial career in finance and business. In more recent years, he has also focused efforts on philanthropic activities. He holds an Honours Degree in History and Philosophy (1967) from SMC and an LL.B. (1970) from the University of Toronto. He is married to Diana Collins Bennett (SMC 1968). His siblings – Sue Brown (SMC 6T2) and Hilary Bennett (SMC 7T4) are also alumni.

Friends, colleagues, and former students are remembering Professor Emerita Janine Langan as a woman deeply devoted to her faith, family, academics, and students. Dr. Langan, who founded St. Michael’s Christianity and Culture Program, died suddenly on Saturday, December 11, 2021 in Toronto. She was 88.

A native of France, Dr. Langan received her first degree at Smith College in the United States, followed by further studies in France, and then a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Toronto. She was particularly noted for her course on the Book of Job and the question of why innocents suffer.

“She was indefatigable in her work to promote the study of Christianity from a variety of academic perspectives and in 1979 she lobbied SMC and founded the Christianity and Culture Program,” recalls Interim Principal Mark McGowan, who met Langan when he arrived at St. Michael’s in 1991 to teach. Dr. Langan served as the program’s coordinator from 1979 to 1987.

“She gathered a multidisciplinary teaching cadre which included her husband Thomas, who was in the SMC/UofT Philosophy Department, and Dr. Kenneth Schmitz, a fellow philosopher from Trinity College,” says McGowan.

Describing Langan as possessing “a forceful but charming personality” he says that she “laboured tirelessly for her fledgling program.

“Above all she was dedicated to her students and founded a club called the St. John Scholars, where students could deepen their studies in Christianity through service, retreats, and travel (to Rome,)” he notes. “Janine particularly loved for her students to access Christianity through art, and I remember her long conversations with Henri Nouwen, with whom she shared a love of Van Gogh. She invited Nouwen to teach several guest lectures in the program.”

For colleague Dr. Giulio Silano, who taught alongside Langan in the Christianity and Culture Program, “what remains is the irreducible originality of her vision for C&C.

“Against the dominant trends in Catholic institutions of higher learning of programs that presented lay people with dumbed down versions of programs meant for clerics, Janine devised a program that took seriously the call of the laity to holiness and so began with the requirements of the lay state,” he says. “Her insistence that the artistic, literary and historical dimensions trumped the easy theological option so often taken by other institutions has proven difficult to maintain in its integrity against the easier option, but it retains its intrinsic originality and fascination.”

Daughter Claire Langan describes her mother’s approach to teaching as “a true vocation, and one that went beyond the traditional four walls of the classroom.”

Adding that her mother’s students weren’t just those enrolled at St. Michael’s but pretty much anyone she encountered, from priests and seminarians to lay people of all ages, Claire recalls her mother regularly opening the family home to discussion groups for a variety of people.

“It was wonderful that St. Mike’s facilitated the creation of this program. My mother was dedicated to passing on God to the next generation,” she says.

Alumna Joe-Anne Boyle, a Christianity and Culture graduate from the early 1990s, describes the program as “introducing people to the treasures of the Church. It awakened the spirit of the Church for people.”

Boyle, who remained friends with Langan over the years, remains particularly grateful for her mentor’s firm belief in experiential learning, calling her a groundbreaker, and says she received far more than she expected from the program.

“I entered St. Mike’s thinking I was going to have a great professor but I also discovered a great friend.”

For Boyle, Langan was someone who took firm stands but had respect for all, someone with impressive “moral fibre.”

Today Boyle is a high school teacher and remains particularly impressed by the new Christianity & Culture graduates she meets as colleagues.

“They are mature and well versed in the history of the teachings of the Church, as well as appreciative of the Church’s beauty.”

Collegium Member Msgr. Sam Bianco knew Dr. Langan from his time as rector of St. Michael’s Cathedral and then as pastor of Corpus Christi Parish in east-end Toronto.

“We would often chat about things theological after Mass,” he recalls. “She spoke of teaching students about ‘critical fidelity’ to their faith and cared not only about the intellectual wellbeing of her students but also about them personally and what was happening in their lives. She was a true woman leader in the Catholic Church.”

Over the years, Dr. Langan was honoured numerous times. In 2006, she and her husband Thomas received papal honours for their contributions to the Church. She was named a Lady of St. Sylvester for her work in the Christianity & Culture Program, as well as for her adjunct work at St. Augstine’s Seminary, while her husband Thomas was made a Knight of St. Sylvester for his work in Catholic education.

In 2016, she was presented with the Catholic Teachers’ Guild Jean-Baptiste de la Salle Award for her work in Catholic education.

The year 2017 saw the introduction in the annual Langan Lecture in Christianity and Culture at St. Michael’s.

Recently, Dr. Langan noted in a public address that “…at university, you can learn to expand your community from family and friends … to all of mankind.”

Daughter Claire notes that her mother taught right up until her death, serving on the faculty of Mary, Mother of God School in Toronto, an independent Catholic school.

Silano echoes the notion of Langan’s life remaining full.

“Janine…was still volunteering four days a week to teach high school kids at Mary Mother of God school…With one of her book clubs, she had just finished a multi-year reading of the Divine Comedy. People who had been her students four or five decades ago were still on her prayer list and in steady contact with her, seeking her wisdom as they tried to make sense of their mid-life (or later) circumstances.”

Predeceased by Thomas in 2012, Langan leaves five children and 11 grandchildren.

A funeral Mass is to be celebrated on Monday, Dec. 27 at 10 a.m. at St. Basil’s Church.

University President David Sylvester says the University is considering ways to honour Dr. Langan when COVID restrictions ease. Plans will be announced in the coming months.

Dr. Adam Hincks, S.J., holds the Sutton Family Chair in Science, Christianity and Cultures at the University of St. Michael’s College. Dr. Hincks, who specializes in physical cosmology, completed a B.Sc. in physics and astrophysics from U of T in 2004. In 2009 he earned a Ph.D. in physics from Princeton University and then entered the Jesuit novitiate in Montréal. After pronouncing vows in 2011, he pursued philosophical studies at Toronto’s Regis College and later did a Bachelor of Sacred Theology at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University. Returning to Toronto, he worked on a Master of Theology and Licentiate in Sacred Theology at Regis College from 2018–20. He was ordained to the priesthood in 2019.

What Parish Are You At, Father?

“What parish do you live at, Father?” It’s a question I’ve been asked a couple of times since I was ordained last year. The answer—“I’m not based at a parish”—can be unexpected for those who are only used to seeing priests at Sunday mass. The fact of the matter is that most ordained Jesuits are not parish priests, nor have we ever been since our founding in the sixteenth century. The same can be said for those in many other religious institutes, such as the Basilian Fathers who are so important to St. Michael’s College. This doesn’t mean that none of us have parishes—for instance, here in Toronto, Our Lady of Lourdes is served by Jesuit priests and St. Basil’s by Basilians. Nor does it mean that we don’t help out at parishes in various ways. But it isn’t our sole defining ministry.

In my own case, my principal assignment, which I just began in July, is as a professor here at the University of Toronto. To be honest, when I became a Jesuit in 2009 fresh off of a doctorate in physics, I never dreamt that I would come back to the St. George campus, where I had been an undergraduate, as a professor! I figured after the many years of Jesuit formation I would could end up in an academic setting, perhaps at one of the scores of universities we run around the world, but it was only a vague idea.

The position I have begun here is new and unique. Supported by the Sutton Family Chair in Science, Christianity and Cultures, I have an appointment both in the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics and here at St. Michael’s College. The majority of my research is purely scientific, in the area of physical cosmology, or the study of the Universe as a whole. I work on telescopes that observe the very early universe and that map out the cosmos on its largest scales. But with my training in philosophy and theology, I also have an interdisciplinary interest in how science relates to faith and vice versa. And so a good part of my teaching will be precisely in this area—such as SMC371, “Faith and Physics”, which I shall teach in the winter term of 2021.

Still, one might return to the spirit of the question I began with and frame it a bit differently: why should a priest be engaged in research and teaching at a public university? There is the somewhat facile answer that there have been clerics on faculties ever since the first universities of the West arose in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The Church has always valued education and the pursuit of knowledge, and thus her clergy and religious as well as her laity have always contributed to these great endeavours. But looking at the question from within the tradition of my own religious order, I am reminded of the notion of “finding God in all things”, a formula often used to capture a key aspect of the spirituality of St. Ignatius of Loyola, our principal founder.

“Finding God in all things” is not a vague aphorism or a flaky aspiration, but is rooted in the deeply Biblical conviction that as Creator, God is intimately present to his creatures, or, as Thomas Aquinas put it, “God is in all things, and innermostly.” This does not mean that if you use a powerful enough microscope (or telescope!) you will suddenly find scientific “evidence” for God. But it does mean that studying creation—whether through the lenses of the humanities, the social sciences or the natural sciences—can be a springboard to contemplating its Creator. “Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things” (Phil. 4:8, NABRE). And ultimately, it is “contemplation of divine things” that is one of the principal tasks of those of us in religious life.

So I consider myself blessed to have this opportunity for contemplation, even if the busyness of the job means that I can’t always advert to it! I am looking forward to collaborating with all my colleagues at this university—fellow faculty, other researchers and students—as we lift our minds to consider true and lovely things “worthy of praise.” Not everyone contemplates science from within a religious worldview, and of course there are some who think such a stance is ludicrous. But I’m excited that St. Michael’s College has opened the space to explore it further, and I’m excited to see where it leads. I trust it will make me a better scientist, a better Christian—and a better priest.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Nisheeta Menon is a graduate of St. Michael’s Christianity & Culture program and holds a Master of Divinity degree from the Faculty of Theology. While studying theology she served as the Social Justice Co-ordinator and Student Life Committee Vice-President. She is now a high school Religion teacher in Mississauga, where she hopes to continue her co-curricular work serving her school community in the areas of equity and diversity education and chaplaincy.

Wandering in the Desert

Autumn is a time of year I have always loved. As a student, I looked forward to transitioning back into school and the start-up of all of the clubs, sports, and activities. Now, as a secondary school teacher, my appreciation of this time of year has only increased. It is around this time that the life of a school starts to take shape—student leadership, chaplaincy, athletic teams, volunteer and outreach initiatives, arts programs, etc. Plans turn into reality and the school begins buzzing with activity, creativity, and life!

This autumn, as you might imagine, looks very different. The beginning of the school year was tumultuous, to say the least, and some of us only received our teaching assignments in late September. A number of teachers, like me, were designated to teach the online cohort and, with that, we have sunk into the routines of virtual teaching with considerable reluctance.

Students continue to be moved in and out of our courses due to a host of scheduling issues while the quadmester is rapidly progressing toward its end date in the second week of November. The tight timeline forces teachers to compress the curriculum, either speeding through important concepts or eliminating them entirely. The students “attend” class daily but are behind their screens while we are behind ours, and, even when our cameras are on, there is a palpable discomfort.

In a regular classroom, these students would know each other quite well by Grade 12, and they would continue to build connections with one another throughout their time in a class like mine. In the virtual environment, however, students in my classes are from all over the school board and, despite my efforts, their interaction is limited. As well, during the average school day, my colleagues generally remain isolated in their own classrooms (for good reason), leaving the staff lounge and department offices empty. The school is eerily quiet and the few faces you may pass are hidden behind masks. This is a far cry from the Thanksgiving liturgies, staff potlucks, and Student Council Haunted House tours of the past.

For most teachers, even those with in-class cohorts, the laments are the same: feeling disconnected from the students, being unable to teach and assess in an effective way, concern over students with access issues or learning challenges, and a general lack of guidance and support. At the same time, we watch the news as reports of COVID-19 cases in schools rise and we check in with some of our close friends and family as they await the results of their tests. We miss the loved ones who are outside of our social bubbles, and we worry about them, and ourselves. It is difficult to be hopeful.

One day, as I discussed these grim realities with a colleague, I confessed I was having a difficult time staying optimistic and energized, but that I was simultaneously feeling guilty about this because I also acknowledge how privileged I am in many ways. She offered one of the most helpful comments I have heard throughout this pandemic: “Of course you’re having trouble staying hopeful! What do you expect? We are the Israelites in the desert! This is not the Promised Land!”

Coincidentally, it was at that very time that I was in the midst of discussing the Exodus story with my Grade 12 Religion class. We had talked about how the Israelites in the desert must have felt a sense of hopelessness, fatigue, monotony, and an underlying fear that they might never actually reach the Promised Land. It is difficult to imagine that they ever woke up optimistic and chipper, ready to spend another day wandering in the desert!

During this pandemic, part of the struggle which so many of us put ourselves through is trying to make our lives as close to what they were pre-pandemic as possible. Of course, this is nearly impossible, and our failure to meet our self-imposed standards only heightens our anxiety. By acknowledging that we are “in the desert,” perhaps we can give ourselves permission to feel a little lost, at times hopeless, and generally unable to think more than a few steps ahead at any given time.

My most gratifying class thus far occurred when I shelved the curriculum for one day and chatted with the students about how I was feeling. As a teacher, and one of the only adult influences outside of their home they have regular access to right now, I know that modelling for my students the fact that it is okay to be struggling is perhaps the most important lesson that I can offer. After sharing with them a little about what was weighing on me, my students quickly piped in with words of validation and encouragement, which led to other students sharing their particular burdens, which in turn led to more encouragement from the group. Despite the distance between us and the glitchy internet connection, our discussion rolled on until the end of the period. There was laughter, exclamations of, “Oh my gosh! Me too!” and quiet, muffled sniffles at times. We never got around to our lesson on the Book of Exodus that day, and yet I am certain that we came to a better understanding of how the Israelites were able to survive—and find deep meaning in—their time in the desert together.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Jean-Olivier Richard is Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream, in the Christianity and Culture Program. A historian of science by training, his research and teaching interests include the relationship natural philosophy with Christianity with science in the early modern era, Jesuit history, environmental history, and the history of alchemy, astrology, and magic.

Night Sky and Quietude

On June 17, I decided to set up a tent in the backyard of my partner’s parents, thereby adding a room to what was beginning to feel like a crowded house. My girlfriend and I brought mattresses, pillows, sleeping bags, and munchies. I also decided to install my Meade ETX 90, a reflecting telescope I had purchased a couple years ago and neglected to use since. I figured that on a clear night in Ottawa’s suburbs, it would find better use than in dazzling Toronto.

Around 3 a.m., we woke up to a starry sky, with Vega and Arcturus above our heads and a handful of planets lined up within the narrow band of the Zodiac. In the south, majestic Jupiter lorded at its zenith in conjunction with Saturn. Red Mars was lagging further to the East, next to Neptune, invisible. The waning crescent Moon, with Venus by its side, had yet to rise. Over the next two hours, we turned the telescope to each of these celestial bodies, trying different lenses and observing with childlike excitement. My girlfriend saw, for the first time, Jupiter’s four largest satellites—the same Galileo discovered with his spyglass in 1610—as well as hints of the giant’s darker belts. Even more delightful, to both of us, were Saturn’s rings, which we could see distinctly, like a pair of bright handles. Then, just before dawn, the ancient Moon’s familiar wink was made unfamiliar. Next to its shadowed face, Venus was showing its crescent. At that point, our excitement had ceded place to a kind of contemplative wonder, mixed with serenity and sunlight. With our naked eyes, we had observed and experienced what astronomers of old described as the wheeling of the celestial spheres around Polaris, the axis of the world. It was a wakeful night well spent.

Over the next couple of days, my mind was busy pondering Plato’s Timaeus, a speculative account of the creation the universe I teach in some of my Christianity and science courses. Therein Plato argues that the cosmos was made by the Demiurge, a divine, benevolent craftsman who ordered his materials mathematically and beautifully, in the likeness of eternal, unchanging forms. The Demiurge not only created the gods (including the planets) but also individual souls (each one tied to a guardian star), whose bodies He let the lesser deities shape from imperfect matter. Plato teaches that our souls, trapped as they are in their fleshy shells, tend to be confused and disorderly, having lost sight, from the moment of their birth, of the divine harmonies from whence they come. For Plato, contemplation of the wheeling stars—and by extension, the study of mathematical proportions—is the best way to quell our inner disturbances and to restore our quietude. Failing to do so is to risk losing clarity of mind, to condemn the soul to reincarnate in critters less suited for philosophy than human beings: birds, brutes, or—God forbid—fish!

For sure, contemplating the heavens was not a source of excitement for Plato in the way it can be to city dwellers today, but it was just as salutary. Plato’s great insight was that education is transformative: we become what we study, and we must therefore be mindful of our intellectual diet. In trying times, when we feel trapped in our heads and in our houses, it pays to look up, and emulate the stars.

Read other InsightOut posts.

June 24, 2020

The University of St. Michael’s College and The University of Toronto Faculty of Arts & Science are pleased to announce that astrophysicist Dr. Adam Hincks, S.J., will be the inaugural holder of the Sutton Family Chair in Science, Christianity and Cultures. The position, jointly supported by Arts & Science and an endowment to St. Michael’s from alumni members Dr. Marilyn and Thomas Sutton, will make a significant contribution to the body of scholarship on the intersection of these three key fields.

Alumni and generous donors to St. Michael’s, the Suttons have long envisioned a position dedicated to examining how Christianity, science and cultures interact and intertwine.

“Marilyn and I are pleased to make this gift of gratitude in support of the distinctive partnership of USMC (St. Michael’s) and U of T. Our education in the Humanities at USMC and Math and Physics at UofT gave us a strong foundation for further education and our professions,” says Mr. Sutton.

The Suttons have found in their own studies that exciting knowledge is found in the spaces between disciplines. The Sutton Family Chair will offer a distinctive opportunity to advance such understanding.

“The inquiries of Science, Christianity and Cultures are informed by intersecting strands of scholarship. This Chair will provide a locus for focused study of those intersections and facilitate the development of new knowledge,” Dr. Sutton says.

Dr. Hincks specializes in physical cosmology, which studies the evolution and overall structure of the universe. In 2004, he completed a B.Sc. in physics and astrophysics from U of T, while also earning the St. Michael’s College Gold Medal for the highest cumulative GPA in sciences for a graduating student. In 2009 he earned a Ph.D. in physics from Princeton University and then entered the Jesuit novitiate in Montréal. After pronouncing vows in 2011, he pursued philosophical studies at Toronto’s Regis College and later did a Bachelor of Sacred Theology at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University. Between these studies, from 2013 to 2015, he was a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of British Columbia. Most recently he has been completing a Master of Theology and Licentiate in Sacred Theology at Regis College. He was ordained to the priesthood in 2019.

“As an alumnus of St. Mike’s at the University of Toronto, where I did the undergraduate Astronomy and Physics specialist programme, I’m proud that my alma mater has created this creative position, and I’m delighted to be taking it up,” he says.

Among his various academic affiliations he is an associate scholar of the Vatican Observatory, while his research includes work with the Atacama Cosmology Telescope and the upcoming Simons Observatory, both located in Northern Chile, that are designed to answer fundamental questions about the history and structure of the Universe. In the past, he has also worked on the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley.

“I’m looking forward to continuing my scientific research in a context that also allows me to examine how it enters into conversation with Christianity and culture, both in the classroom and as a secondary research area,” Dr. Hincks explains.

“Dr. Hincks is a stellar addition to a growing group of very fine core faculty at St. Michael’s,” says Dr. Sylvester. “He reflects the caliber of research and teaching excellence St. Michael’s is providing to all University of Toronto students. Dr. Hincks’s work—especially in studying the interrelationships of Science and Christianity and their relationships to a variety of cultures—disproves the frequent assumption that science and religion have nothing positive to gain from encountering each other. We are very glad to welcome him home to St. Michael’s.”

Dr. Melanie Woodin, Dean of U of T’s Faculty of Arts & Science, agrees.

“The establishment of the Sutton Family Chair will advance research and teaching in multi-disciplinary ways that attest to the breadth and depth of the scholarship and learning that takes place in the Faculty of Arts and Science,” Dr. Woodin says. “I am delighted to recognize the generosity of U of T alumni and longtime supporters Tom and Marilyn Sutton. Their investment in this co-located Chair affirms the importance of creative and meaningful collaborations between the Faculty and one of its valued federated colleges, St. Michael’s.”

Dr. Hincks will begin his four-year appointment on July 1, 2020. The David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics will host Adam’s graduate appointment in the University of Toronto. In addition to teaching courses for the Department and also for the Christianity and Culture program sponsored by St. Michael’s College for students in the Faculty of Arts and Science, Adam will develop a course to be offered jointly for students in both programs, related to religion and science, in the time ahead.

Marilyn and Tom Sutton are graduates from St. Michael’s class of 1965. Marilyn graduated with a B.A. in English and French, completed a Phd at Claremont Graduate University and is Professor of English (Emerita) at California State University, Dominguez Hills. Tom graduated with a B.Sc. in Mathematics and Physics and is the retired chairman and CEO of Pacific Life Insurance Company.

Michael O’Connor is Associate Professor, Teaching Stream, in the Christianity and Culture program and Book and Media Studies. His research interests include music and liturgy and he is director of the St. Michael’s Schola Cantorum and the college Singing Club.

Saturday night, Sunday morning

Saturday night

You were lucky the get tickets for the Tafelmusik late-night concert. You arrive an hour early for check-in, as required, and stand in a well-spaced line in the cordoned-off section of now pedestrianized Bloor Street. Your mask is inspected, your temperature taken, you are asked some routine questions about your health (all rather reminiscent of flying to the US in the old days—when we could do that), and are then directed to your seat, four seats away from the next person, empty rows in front and behind. The tang of bleach competes with wood polish. At least there’s space to put your coat, scarf, and mitts (it has been an especially cold March). You nod at your nearest neighbours, an indistinct gesture that could mean “Why on earth are we here?”

The tiny orchestra is spread out over the whole dais. The string players are all wearing masks, the harpsichordist is wearing gloves, and the oboist is inside a plexiglass booth, standing on a disposable absorbent mat. The choir, of course, has been furloughed—they are supervectors. According to the program notes, which you read on your phone, you’ll be hearing music from seventeenth-century Venice composed in thanksgiving for deliverance from the plague. The oboe gives a note and the strings begin tuning up; at this sound, neither music nor noise, you shiver with unpremeditated delight. It has been almost a year since you heard any live music—other than the neighbour’s daughter practising clarinet. You realize in that instant how heartsick you have become with the diet of autotuned, click-tracked, virtual ensembles.

You can’t take you eyes off the three-dimensional, flesh and blood performers. They make occasional eye contact with each other at beginnings and endings but for the most part, like geese in formation, they sense together the music’s flight, bobbing and weaving as one. Carried along with them, your spirit soars, your pulse quickens. Behind your mask, you chuckle with nervous joy. They play for an hour (no interval, no washrooms, merchandise for sale online only) but it passes in moments. Your final applause is exuberant, reverberant, as you try to fill the space with the appreciation of an absent crowd.

Sunday morning

At St. Basil’s, you join the ticket-holders for the 11:07 mass (“enter through the west door, please stand on the red dots”), where your mask is inspected and your temperature taken. Once the 10:30 mass is over, you file up the stairs into church. Household groups sit together; others sit in isolation. You choose a spot in the sightlines of the camera live-streaming the mass on the parish’s YouTube channel. Your mother will be watching (“No, not lingering adolescent guilt,” you insist: “it will lift her spirits to know she has a proxy at mass”). You greet parishioners whose names you now know from Zoomed faith-sharing sessions. Stilted remarks are exchanged across the voids but, like teenagers, you have learnt to save your most vulnerable conversations for social media. Gloved sacristans lay out all the necessaries next to the altar; there will be no servers.

The entrance hymn is sung by an unseen cantor and although the words are projected onto two large screens, you are encouraged only to hum along quietly (“Singing is worse than coughing”). This suits you, since you are a reluctant singer—unless it’s “Come all Ye Faithful,” “Amazing Grace,” or that bit from the Mass of Creation that everyone knows. You recall the choir director who insisted that singing is all health benefits and no side effects—you wonder how he’s enjoying his humming. Readers proclaim the scriptures from individual iPads. The priest’s homily is polished—which is not surprising given the number of times he has preached it today. Occasionally he turns to the camera to address the over-60s watching from home. He looks tired. You enjoy the reminder that the collection basket has been stood down (“temporarily, of course”), and nag yourself (again!) to go online as soon as you get home to make your donation.

Bread and wine are prepared at the altar. The organ plays softly, a half-disguised melody accompanied by the clink of the cruets on the chalice. The sight of the empty seats conjures up the parishioners who normally occupy them, and your mind’s eye is flooded with images of warm, colourful, singing bodies. In among them, you wonder if you really do see faces of angels, apostles, martyrs—a shimmer of countless holy ones.

Communion is a regimented, high-alert manoeuvre. You make your way forward biddably. Against all reason, you lower your mask. As the social distance collapses to near-zero, the minister deftly drops the host onto your well-scrubbed hands. You exhale your Amen. Back in your seat, you savour communion. You think of those you love, those in need, those who have not made it this far. While the invisible cantor reminds you to taste and see how good the Lord is, your prayers rise on clouds of Purell and latex powder.

After the closing devotionals (St. Michael has been joined by St. Blaise and St. Roch), you leave the church in an orderly fashion (“exit through the east door”). The organ postlude is almost loud enough to drown out the sound of disinfectant being sprayed on the pews as the church is made ready for the 11:44 mass, the last one before the lunch break.

On the long walk home, your mind is a-chatter: yes, togetherness is in your genes, primates love to sing and laugh together, to feast and embrace. But as a rational primate, you have been hearing for months now that your neighbour is a potential biohazard—that you could be a biohazard—and that the only safe space is the digital universe, where viruses are metaphors.

When you get home and inside, you slump against the door, pull off your mask and take several long breaths. You’re exhausted. You’re blessed. You just might be hungry (you’re never sure these days).

The lockdown was not easy; but the opening-up feels much harder.

Sources

Guidelines for rehearsals and concerts during the pandemic have been issued by the German Orchestra Association’s Health and Prophylaxis Working Group and by seven orchestras in Berlin. Two bodies in the US have produced guidelines for the celebration of sacraments: the Thomistic Institute in Washington and the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions. An alliance of singing groups sponsored a webinar on the near future of singing.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Assistant Professor, Christianity and Culture Stephen Tardif is now co-editor of The Hopkins Quarterly, an international journal of critical, scholarly, and appreciative responses to the lives and works of Gerard M. Hopkins, S.J., and his circle. He begins his duties at the same time as fellow co-editor Dr. Michael D. Hurley of Cambridge University.

“I’m delighted to be co-editing the Quarterly, which has been the major journal in Hopkins studies for almost a half-century,” Tardif says. “It’s also a great pleasure to extend The Hopkins Quarterly‘s long-standing connection to St. Michael’s College.” Past co-editors include St. Michael’s Professor Emeritus Joaquin Kuhn, who co-edited the journal for 25 years.

Founded in 1974, the journal publishes academic articles and book reviews, notes and notices, as well as special issues, from new and established scholars. The first issue of the journal under its new co-editors is now available, featuring articles on “The Wreck of the Deutschland” and Hopkins’ and Christina Rossetti’s poetic depictions of flux, and a number of book reviews.