Zach Nixon (SMC 1T8) is a Torontonian living in Ottawa. He holds a BA in Political Science. He began his political journey working in the Constituency Office of Bill Blair, Member of Parliament for Scarborough Southwest. He later served in successive roles under Mary Ng, Minister of International Trade, Small Business and Economic Development, where he played an active role in supporting Canada’s small business sector—especially during the critical period of the COVID-19 pandemic. His work during this time, particularly in helping small businesses weather unprecedented challenges, remains one of his proudest contributions to date. He later served as Director of Operations to Rechie Valdez, Minister of Small Business. In July 2024, Zach joined the Office of the Prime Minister, initially serving under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and now continuing his service under Prime Minister Mark Carney.

When I think of what most people think of politics today, I figure the word that best captures the time we are in is “polarization”. Now more than ever, it seems like no one can agree about anything at all and the political temperature is high. However true some of this may be, it risks turning away our best and brightest from working with our public office holders and missing the greatest opportunities to make a difference in our country.

Polarized as our politics may be, my experience for the past seven years in federal politics has been nothing short of amazing and I have met and worked with incredible people who just want to make a difference.

At St. Mike’s, I got involved in student politics at the encouragement of my residence don and friends during my second week on campus. Being deathly afraid of public speaking, I never thought that this would be an opportunity for me (and I almost skipped out on the required all candidates debate). Nevertheless, I ran and won as a first-year rep on the Student Union and the rest was history. During my time on the Student Union, I made great friends and found in my involvement something that became clear to me in politics–that almost everybody who puts up their hand to help out is doing so because they want to make a positive contribution to their community.

After a few years on student council, I got involved in federal and provincial politics by volunteering for the provincial and federal Liberal Parties in Ontario. These opportunities set me up for what became a seven-year career in federal politics. My first job, working in the constituency office of MP Bill Blair, did not have the high drama and political machinations that you often see on CBC, but rather saw me attending community events and helping regular people with their immigration casework. This was incredibly fulfilling work and speaks to the old adage I have learned in the business that “all politics is local”.

After a few months in that role, I had a chance to move to Ottawa and spent the next few years working for the Minister of International Trade and Small Business, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. I spent hours on the phone with business owners who were looking for just about anybody who would listen to them as they grappled with owning a business during a global pandemic. This was a time when the government was at its best, and where I, at 25 years old, was the only face that hundreds of business owners would encounter–and chances are would ever encounter, when dealing with the federal government. It was a huge responsibility for someone so young, but not uncommon in political life. Oftentimes, I was able to help them secure the funding they needed to keep their doors open, and I’m really proud of that.

Most recently, I have been working in the Prime Minister’s Office as a Regional Advisor. I started this role under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and continue under Prime Minister Mark Carney. In this role, I work with other levels of government, businesses, and organizations in Ontario who are looking to get in touch with the Prime Minister. I travel the province with the Prime Minister so that he can meet Canadians in their communities and hear about their experiences. I learn about cities and towns across this province – all with their own concerns and all with local leaders looking to make their communities better.

I didn’t expect that politics would be the path for me, but I’m glad I chose it. I have travelled to almost every province in Canada and have made lifelong friendships. I’ve learned how our government works and have experiences I will cherish forever. So, if you want to make a difference and have experiences that will last a lifetime, I’d encourage you to take the plunge. There is a world of experience in politics that awaits you!

Read other InsightOut posts.

John Fraresso is currently in his second year of the Doctor of Ministry program at the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology (RSM) and is the Spiritual & Community Life Coordinator at L’Arche Hamilton.

I am very fortunate to be able to witness the blessings and miracles that happen when one more fully surrenders to the will of their soul, which for me is synonymous with God’s will for them.

I am of course far from perfect at this. But I am a case study of what can happen when one does slowly get better at this.

Spiritual progress, not perfection.

When I returned to school to do my Master of Theological Studies degree at St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology in 2019, I expected to complete this two-year degree and move on to the next thing.

Six years later, I have completed my Master of Divinity, am entering my second year of the Doctor of Ministry program at RSM, and witnessed my 100-hour field placement at L’Arche Hamilton transform into something far bigger. Firstly, I am still there. Secondly, I have the honour of being in service of the community’s spiritual & community life. Finally, my doctoral studies will focus on the challenge of spirituality in L’Arche, which has faced head winds with the Vanier revelations, as well as increasing secularization and pluralism.

This journey has resulted in pipe dreams coming true and has also been sprinkled with never-in-my-wildest-dreams moments occurring.

One of these such moments happened recently.

In the fall, I wrote a paper titled Charismatic Authority, Power, and Abuse in Jean Vanier’s L’Arche for Christopher Brittain’s Theology and Power course (which I highly recommend) at Trinity College. After receiving a pretty spectacular grade for it, I was encouraged by my thesis supervisor Jean-Pierre Fortin to submit it to the Canadian Theological Society for consideration to be presented at their annual conference, as part of the broader Humanities and Social Sciences Congress.

Lo and behold, little Johnny presented his paper to a bunch of academics at an academic conference.

What an amazing and humbling experience, something I never in my dreams thought I would do. Compressing a 20-page paper into a 10-minute presentation was a fun challenge. I was grateful that my presentation was so well received by those in attendance and I also got to see some old colleagues that I haven’t seen in a while!

I’m also grateful to Dr. Fortin for the nudge to submit the paper and for the CTS for allowing me the honour to present at their conference.

Read other InsightOut posts.

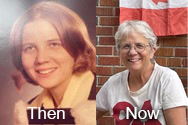

Celia Viggo Wexler (SMC 7T0) is a freelance journalist and author based in Alexandria, Virginia. She received the Governor-General’s medal for academic excellence in 1970 and earned a graduate degree in journalism from Point Park University, Pittsburgh in 1996.

I went to my St. Michael’s reunion mostly for work reasons. I was reluctant because all the women I’d kept in touch with, and whom I knew from my high school and college days, were not able to attend.

But thanks to the invaluable assistance of Lisa Webb, St. Michael’s manager of alumni affairs, I was invited to promote my book, “Catholic Women Confront Their Church: Stories of Hurt and Hope.” Lisa even created a “Meet the Author” event for me at the Dodig Family Coop! During a stressful time for her, she was unfailingly gracious and good-natured. (Fellow “Western” Ray Shady introduced us by email.)

But the event gave me so much more than the chance to sell books.

Everywhere I turned, there were opportunities to reach out and meet new people, or to reconnect with alums I hadn’t known well, but now had the chance to know better.

I visited a campus that was deeply welcoming, from the moment I entered the Loretto College chapel for Mass to the conclusion of the excellent alumni reception and dinner on Saturday night.

All the emotions I had attached to St. Michael’s came flooding back. This campus made me feel safe and accepted. I was the greenest of coeds, never having dated, bookish but absolutely clueless about the mores of the late ‘60s. In my home country, the United States, campuses exploded in demonstrations against the War in Vietnam.

I was on the side of the protestors, but appreciated that I was at a campus where the war did not impinge on my growing up, my excellent classes, my ability to think deeply, to make friends, and even write for The Mike, the college newspaper.

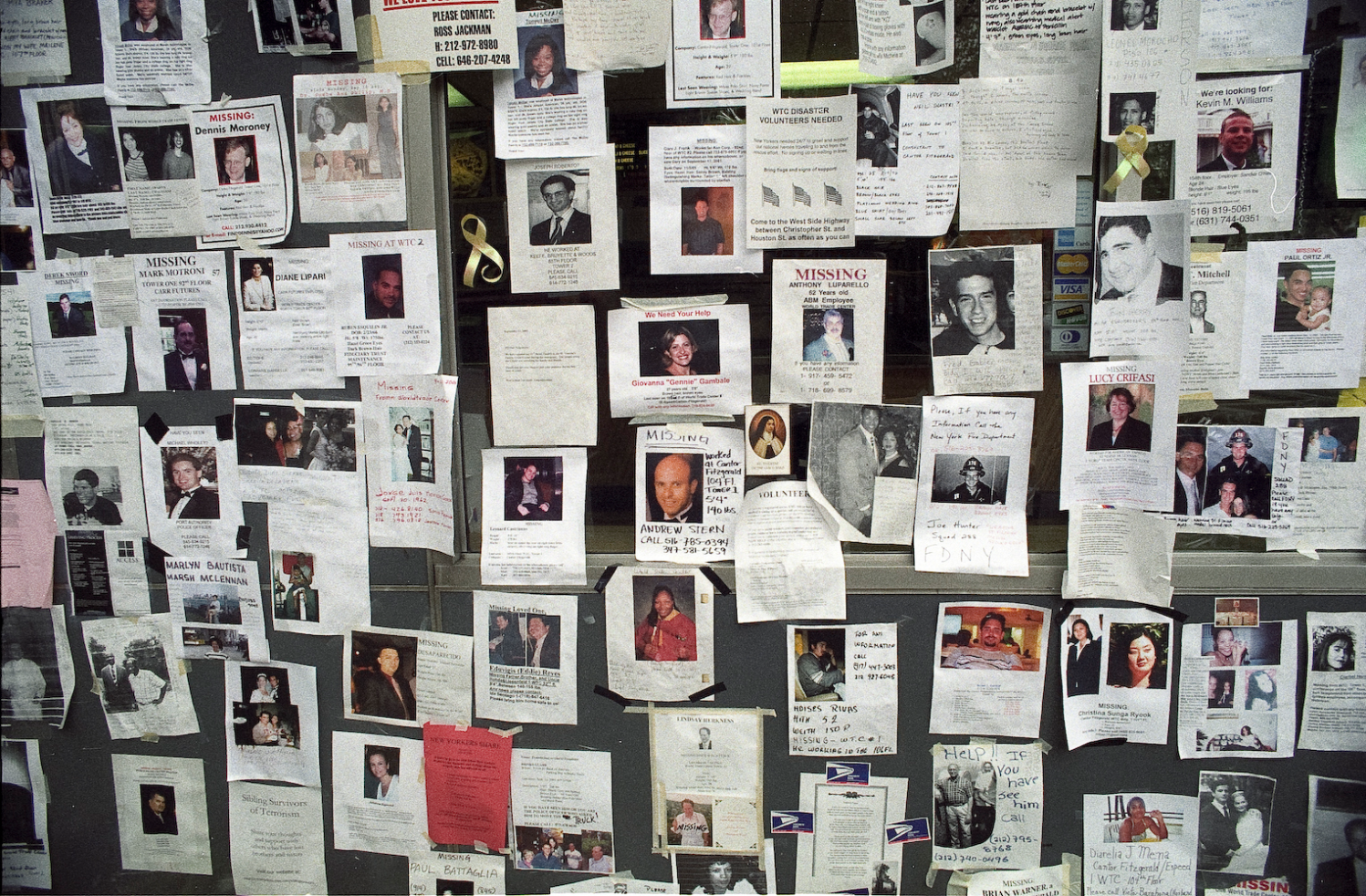

That sense of safety returned to me once again during reunion weekend. St. Michael’s felt like a refuge, albeit a brief one, from the aftermath of our recent presidential election. In my country, I had seen the rule of law crumble bit by bit each day as a new administration flouted laws and the U.S. constitution to not only try to bully Canada but also imperil immigrants, threaten journalists, and dismiss tens of thousands of dedicated civil servants.

But I felt more than safe at St. Michael’s, I felt known, appreciated. I met Dr. Michael Salvatori (pictured in the accompanying photograph), Director of Continuing Education at the university, whose zest for reaching out to the larger community with innovative courses was infectious. He let me know that he had started reading my book and how much he enjoyed it! I even had a delightful chat with President Dr. David Sylvester about his academic specialty, mediaeval history and economics, and his wife’s search for long-lost Caravaggios.

As it happened, just a few visitors came to the COOP to meet the author, when they could enjoy the gorgeous weather.

But some St. Michael’s staffers were kind enough to stop by and purchase books. l also gave a copy to one student, so curious about life and her place in the world, and so full of questions about her future. I thought the book might help.

I started writing my book in 2013, after the stern Pope Benedict XVI chastised women religious for their advocacy for social justice. I wasn’t sure I could remain a feminist, an accomplished professional who believed in women’s equality, and a Catholic. I needed guidance about how to resolve these doubts. So I looked for other women like me, who were struggling with the same challenge.

I found nine exceptional women from both Canada and the U.S., who told their stories freely, and spent hours with me, voicing their frustrations with the institutional church and its attitude towards women, yet also expressing their commitment to their Catholic faith.

Late last year, my publisher released the book as a paperback. Since the paperback came out, Pope Francis has died, and we now have a new pope, Leo XIV. We don’t know how he will perceive the role of women in the church. But I do know that voices of Catholic women are even more important at a time when women risk the progress they have made not only in the church, but in the world.

And I firmly believe that St. Michael’s College will help shape that future, training the next generation of women leaders and scholars.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Paul Babic is a second-year MDiv student at the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology with a background in Philosophy and Religious Studies from McMaster University. He also works as the Projects Officer in the Office of the President at Regis College. With his MDiv, he hopes to help and serve those “who may feel as though God has abandoned them.” In his spare time, he enjoys blogging, copious quantities of coffee, good food, good conversations with friends, and long walks

I don’t normally talk about my religious experiences—much as I do talk about religion—but I thought today I would share one with you. This happened maybe three years ago now as I was walking around my (then) home of Hamilton. Like many Canadian cities, Hamilton has started to look a bit rough around the edges: there are people struggling with addiction, homelessness, and poverty. If you walk through a city in North America today, you’ll probably see them. Maybe you even drop a coin in their cup, but I’ll bet most times you walk past them as I do, too.

So, there I was on a beautiful summer day, walking through downtown Hamilton, when a homeless man came up to me for change. At first, I simply passed him by with the twinge of guilt I normally feel when confronted by the inequities of modern society. But then as I was passing, I looked closer, and bright as the sun, I felt like I was looking at the face of Jesus Christ. Not the Jesus you see in churches, mind you. In fact, it’s not as though his face had changed at all, and yet my perception of it did. There was a disarming peace or innocence about him that I couldn’t ignore. So, I gave him some money and wished him well. Seeing Jesus in that man on the street, I am reminded of Christ’s words:

Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.

—Matthew 25:45

That encounter has stayed with me, and I think about it especially now, as we welcome a new pope—Leo XIV—whose words echo that same call to know Christ in the suffering and unseen. One sister I have the pleasure of knowing thought that we might be in for a Francis II. She was right in a way: Robert Prevost’s middle name is Francis. But for his papal name, he chose Leo, perhaps as a call-back to Leo XIII, who famously wrote Rerum Novarum, an encyclical on capital and labour. Writing at the onset of modern industrial capitalism, Leo XIII decried the indignities wrought by the economic system of his day. And so, in our era of once-again rising wealth inequality, I find this call-back to our last Pope Leo rather timely.

As Catholics, we believe that all human beings are dignified by the image of God which they bear. And while this may be a profound truth, we are reminded time and again in Scripture that theory without praxis is not enough:

Those who say, “I love God,” and hate a brother or sister are liars, for those who do not love a brother or sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen.

—1 John 4:20

When I first heard this verse in the pew, I perked up a bit. Such a revelation to be told, as one in search of God, to begin by loving those you can see. By loving others, we also love God. Thus, remembering the dignity of our fellow human beings, Pope Leo said at his inaugural Mass:

In this our time, we still see too much discord, too many wounds caused by hatred, violence, prejudice, the fear of difference, and an economic paradigm that exploits the Earth’s resources and marginalizes the poorest. For our part, we want to be a small leaven of unity, communion and fraternity within the world. We want to say to the world, with humility and joy: Look to Christ! Come closer to him! Welcome his word that enlightens and consoles! Listen to his offer of love and become his one family: in the one Christ, we are one.

Now, as I reflect on Pope Leo’s words, I remember that man and the many others just like him. Dare we seek Christ in the marginalized of our world? Do we feed the hungry, clothe the naked, welcome the stranger, visit the imprisoned, and—most difficultly—listen to their stories, as Jesus had asked? It’s my great expectation that with this new papacy that is precisely what we are being invited to do.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Michelle Wong is an SMC student entering her fourth year, majoring in Book & Media Studies (BMS) and double minoring in Women & Gender Studies and East Asian Studies. Beyond her academic life, Michelle loves to read, write, listen to different genres of music and discover hidden gems to eat around the GTA. She is currently serving as the The Book & Media Studies Student Association as well as the Student Representative for the SMC Senate. With her pen (or, technically, keyboard), Michelle is passionate and enthusiastic about storytelling and being a reliable mentor to those around her. She aspires to become a journalist—maybe even a museum/gallery curator—to showcase the experiences and emotions of others and help give spotlight to those who cannot have their voices heard.

If you ever approached the first-year me and told her that she would become the President of the Book & Media Studies Student Association, she would look at you with an obvious expression of confusion and laugh nervously while brainstorming a response. Clearly failing to do so, she might end up just nodding and smiling, while quietly replying with an ever-so-hesitant thank you.

Truthfully, I am still in a bit of disbelief—the girl who was once afraid of socializing with other students, and didn’t believe that she would be able to accomplish anything significant during her university career, has come so far.

When I finished my first year, like many other first-years, I had to choose my programs and how I wanted to continue my undergraduate degree. I was determined that I would be doing double majors in East Asian Studies and Women & Gender Studies, yet it felt like something was missing. I was not quite sure what, but I did not feel completed or satisfied doing these two majors; that was until a dear friend of mine introduced me to the Book & Media Studies program.

A bit hesitant at first, I was afraid that I might not have what it takes to excel in the program and that it would be too philosophical/theory-based. As you can tell, I was proven wrong. My choice to major in this program was probably one of the best choices I have ever made during my time at the University of Toronto.

You may think I am exaggerating (I would, too, if I were you!), but because I enrolled in the BMS program, I decided to transfer to St. Mike’s as well. These two decisions were really the ones that altered the direction of my academic career, allowing me to experience and take part in so many opportunities on the SMC campus.

Through the BMS program, I was able to find friends I instantly connected with and can spend hours talking to. Whether it was expressing our admiration and fondness for Prof. Kit MacNeil, or how much fun Prof. Iris Gildea’s classes were, or how many classes we want to take but can’t because of the immense competition during enrollment and needing to prioritize completing our other programs instead, I was able to experience these thanks to my decision to enrol in the BMS program.

For the first time, I truly felt like an actual university student with friends I can talk to about the courses and professors from whom I can seek academic guidance and feedback. I have had so many conversations with professors in the program, and they have demonstrated to me their passion for what they are doing and teaching it to students, all inspiring me to stay true to my passion and want to continue learning from them.

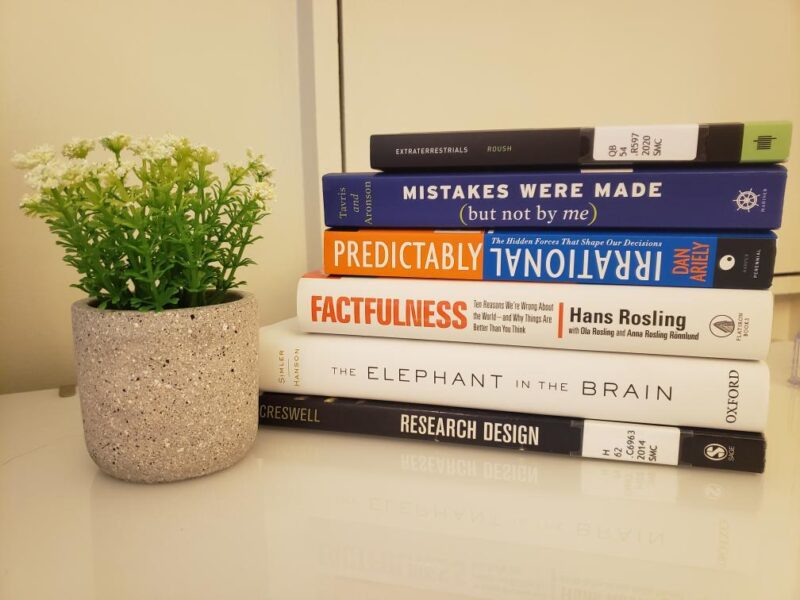

The Book & Media Studies program also introduced me to my love for printing, bookbinding, and learning about different types of medium beyond Western culture. Working with the letterpress machines in the Print Studio at the John Kelly Library will always be a fond memory of mine and something I would have never been introduced to if I had not enrolled in the BMS program.

As a commuter student, it is inevitable to feel like you do not belong anywhere on campus. Yet, transferring to St. Mike’s has really made me feel like I belong, that there is somewhere I can rest and seek help if needed. Moreover, I was able to partake in so many opportunities and meet so many new people because of such an accepting and welcoming community.

Prior to taking on the role as President of the BMSSA, I was the Journalism Editor for the Windrose SMC Yearbook and, through this role, I witnessed firsthand how inviting, uplifting and enthusiastic the SMC community is. I was able to attend my first-ever college formal (it was unbelievable) and connect with other like-minded individuals with whom I shared many laughs.

Now that I am given the opportunity to take on the role as the President of the BMSSA, I truly hope to share the same love and fondness I have for this program and the professors with all the other students who are part of Book & Media Studies. With the rest of the executive team, we hope to host many events for students to connect and truly see what makes Book & Media Studies so unique—the joys, potential and opportunities. There’s just so much to love about this program.

Read other InsightOut posts.

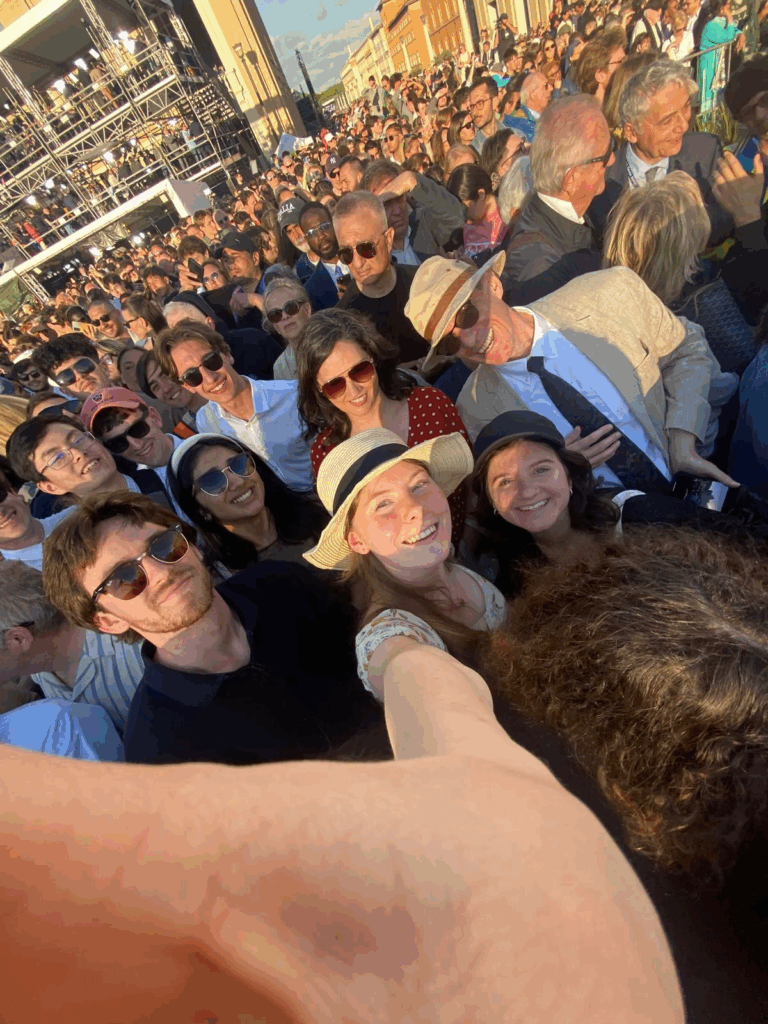

Michael O’Connor, Associate Professor in the Teaching Stream of the Christianity and Culture and Book and Media Studies programs, and students from the Gilson Seminar witness the white smoke in St. Peter’s Square.

Michael O’Connor is Associate Professor, Teaching Stream, in the Christianity and Culture program and Book and Media Studies. Since 2022, he has held the W. J. Bennett Family Chair of Christianity and the Arts.

When we started planning the Gilson Seminar’s trip to Rome over a year ago, we had no idea that it would begin less than a week after the funeral of Pope Francis and that it would coincide with the conclave that had just elected his successor, Pope Leo XIV. Alongside all the thoughts, feelings, and hopes, there was a practical question: How is this going to impact our schedule? We soon became aficionados of “Universi Dominici Gregis,” the legal document that lays out the timeframe and the procedures to be followed. We put in place a plan B for every eventuality.

On the first day of the conclave, we took our planned trip to Assisi, returning to Rome to see news of the black smoke.

On the following day, we were graciously welcomed to the Vatican’s Secretariat of State by Archbishop Paul Gallagher (Secretary for Relations with States). He had cannily moved our meeting earlier, so that we would be finished before the first smoke of the day. When that came around noon, black smoke again, we set off on our afternoon’s activities, knowing that the cardinals were having lunch and a nap. We got back to St. Peter’s Square around 5 pm and settled into a location where the Piazza meets the Via Conciliazione. From there, we witnessed the white smoke above the Sistine Chapel about an hour later.

Some of our students share their reactions:

There was one downside. The needs of the papal election meant that some parts of the Vatican Museums were closed to visitors. But as one of our group said, “I’ll take a conclave over the Sistine Chapel any day!”

Deepthi Claude is a third-year undergraduate at the University of Toronto majoring in Health and Diseases, and Physics. She is an occasional writer who enjoys the art of expressing and evoking feelings through her short pieces.

To all the mothers and children who feel misunderstood

I was three when you dropped me off at school with two pairs of eyes filled with tears. You helped wipe my tears while still being firm to make sure I got the education that I deserved and needed. It was my first day at kindergarten and I was afraid. You were all that I’d ever known, given that dad was working in another city. I woke up to your voice and warm cuddles; you fed me, bathed me, taught me how to play, read, and write, read me stories at night and lulled me to sleep by singing my favourite lullabies. I never heard you complain, although it would’ve been frustrating and hard to have done it all alone and with no one to offer you support. I didn’t make it easy for you either. Yet you never lost patience but, rather, made sure you provided me with a space in which I could grow without having any issues hindering my path.

The next time I can properly recall, I was six. You knew I sang well but you also knew that I did not like being separated from you. So, you would slather mosquito repellents on every inch of your exposed skin to sit outside my vocal class. I would come out in the middle of the class to ensure that I wasn’t abandoned, only to see you waving at me. I would go back to class, completely at peace, feeling supported, reassured, and loved without knowing that the effect of the mosquito repellent had long worn off and that you were sitting outside while swarms of mosquitoes were having a go at you. After class, you brought me back home and listened to me when I wanted to tell you about every minute detail that happened during class. I then proceeded to throw a tantrum over wanting a sibling right that very moment. You calmed me down and told me that one day, I could have one — and I did when you had my brother.

Then, I was suddenly fifteen. I started going out more with friends. I started spending a little time outside to have fun. But I would never step out of the house before telling you or making sure that I had your approval to do so. I still tell you everything that goes on in my life. I enjoy spending time with you and gain the benefit of all your cuddles. You occasionally complained about me spending a little too much time outside and I was occasionally mad at you for not being understanding of the ‘little’ independence that I got.

Eventually, I was eighteen. I started going to the university that I picked to pursue post-secondary education. I was swamped with classes but, somehow, I also found the time to hang out with friends more often. In the same fashion, I got involved more in my college community and started staying out late. I always came home but gradually the time spent with you decreased and I answered your queries about the day with a simple “It was fine.” I told myself that I was simply too tired from the day to talk about it with you but deep down I knew I felt distant from you because every time you brought up the fact that I was staying out late without informing you first, I felt like you just wanted to pick on me. Over the course of a few months, this escalated to heated arguments and talks about independence and respect that further pulled us apart.

Now I’m hardly a month away from turning twenty. You just told me that the reason you were worried about me staying out late is because I don’t spend enough time with you and that leaves you feeling like you are losing me. I find it so adorable and also a little ridiculous that I laugh but then I see tears in your eyes and I am reminded of the tears that I witnessed when you first dropped me off at school. I try to jump into your arms but I don’t fit in there the same way I did when I was three or eight or fifteen. Maybe because I’m hardly a month away from being twenty now. But you fit very well in my arms. So, that is what we do. I assure you that you will never lose me to anybody or anything in this world because nothing comes between the bond that a child and mother share. There are other relationships of the same intensity, but they involve different emotions. As such, there exists a unique bond that transcends the physical self between a mother and her child, and I am fortunate to have this relationship. I will always love you for the woman that you are and for the woman that you raised me to be.

Love,

Your daughter

Read other InsightOut posts.

Marilyn Grace (SMC7T5) is a class representative for the Class of ‘75. She earned a B.Ed. in 1977. Married to Jim Grace (SMC6T7), she taught Religion, English, Drama, and did Guidance and Chaplaincy at two Catholic high schools in Toronto-Cardinal Newman High School and Cardinal Carter Academy for the Arts. She retired in 2012 or ‘switched gears’ to do retreat facilitation at Scarboro Missions and now at The Mary Ward Centre. Marilyn and Jim have four children and three grandchildren all of whom – as she notes, “blessedly,”– live in Toronto.

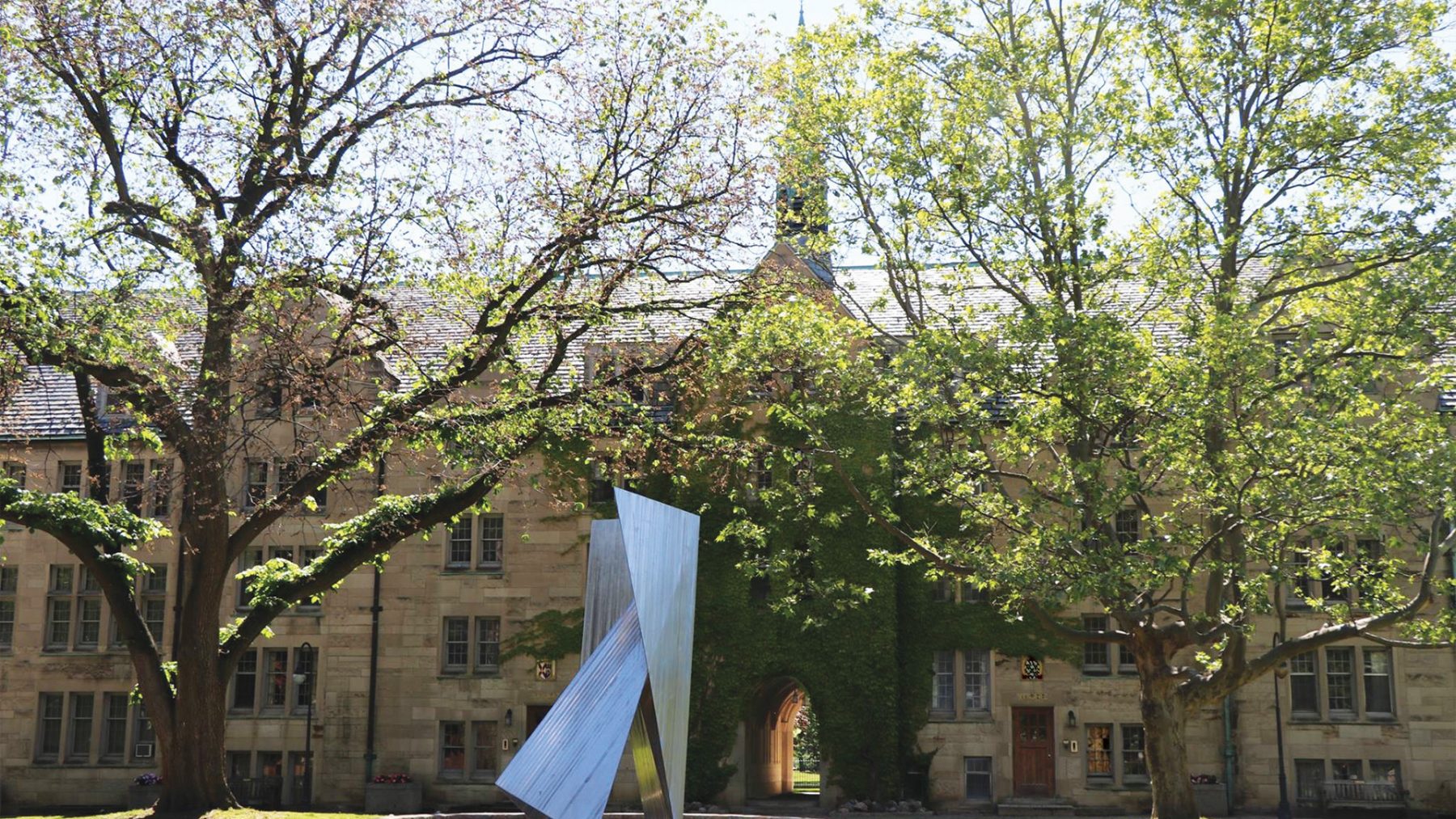

Remember when you could stay up half the night and then roll into class? Remember when you first stepped onto campus? Remember meeting all those new people, some of whom would become friends for life? Remember snowball fights in the quad? Remember being thankful that you weren’t killed when you crossed Queen’s Park to get to the other side of campus? Remember when St. Joseph’s was a girls’ residence? Remember when you couldn’t talk at the Kelly Library?

Rather than remembering, why not Return? You are invited to remember all those key moments from your youth and to return to celebrate them and one another at the 2025 St. Michael’s College, U of T Reunion. We are especially excited to see and celebrate those of us who graduated 50 years ago (I know, I can’t believe it either) and those who graduated 55 years ago. They promised me that there would be name tags, so worry not. Also, the campus is quite accessible so if you do have mobility issues, once again, worry not.

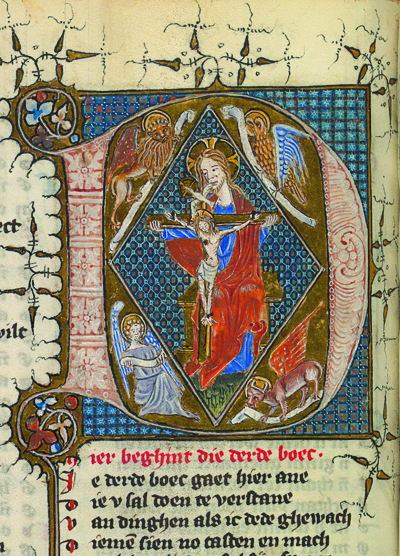

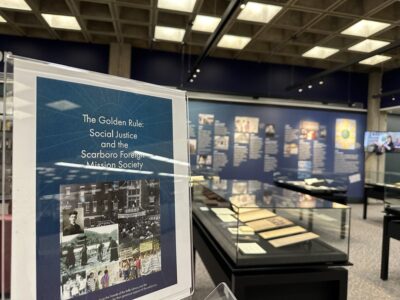

Even though we may not be able to stay up all night, we still have some party in us! What an opportunity to come back and connect with those we first met 50 or 55 years ago. This is your chance to reconnect if you’ve lost touch and I promise that there won’t be snow in May. So rather than snowball fights in the quad, we can connect over the many events being offered at St. Michael’s and U of T. Great news too… there is now a light at Queen’s Park so you can cross safely to get to the other side. Even though St. Joe’s is no longer a residence it is still going strong as part of Regis College with many courses offered in theology and religious studies. You can visit the Kelly Library and be surprised that there are no books on the main floor anymore, and you can enjoy a coffee in what was the old reading room!! Yes, there is now a café in the library, and you’re allowed to talk! Come and enjoy the exhibit of the Golden Rule and the work done by the Scarboro Mission Fathers or join the tour of Fr. Dan Donovan’s collection of artwork.

You can reconnect on Friday, May 30 at the opening Mass which will be held at the Loretto College chapel and then the 1970 and 1975 graduates will enjoy lunch in the Charbonnel Lounge. During the day there are activities and events at St. Mike’s as well as U of T. You can look at the six residences on campus and try to remember where your room was and if you were a day hop you can check out the renovated COOP. The evening events will include a barbecue and, of course, pub time!

Saturday at St. Mike’s includes a lecture on “Freedom and the Modern World: Lessons from Hegel and Kant” given by Douglas Moggach (7T0) or enjoy an Historical Journey of the campus entitled ‘Footprints in Time: A Historical Journey’. The afternoon offers a panel discussion on ‘Contributions of Women to Academics’, or you can enjoy a movie at Alumni Hall. A reception and banquet will be held Saturday evening for those who graduated 50 or 55 years ago.

As a member of the last Western Year class held at St. Mike’s, for those of us who came either from the States or provinces that did not have Grade 13, I am looking forward to meeting and reconnecting with those classmates even if you did not continue at U of T or St. Mike’s. You are most welcome to attend the reunion! In fact, there will be a special Western year meet up at the BBQ in a mini-reunion area that will be provided.

I will certainly miss those who cannot join us, like Fr. Belyea, Fr. Madden, Fr. John Kelly, Fr. Gardner and all those profs who had a major influence on my life or those classmates who have died. However, I am looking forward to those of us who can join in whatever way possible. So don’t delay or procrastinate like we did on those assignments years ago, and register for the weekend of remembering and returning, May 30-June 1. Hope to see you there.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Prof. Gerard Ryan, SJ, is the Scarboro Missions Chair in Inter-religious Dialogue and Director of Msgr. John Fraser Centre for Practical Theology at the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. For Earth Day, we asked Fr. Ryan to share thoughts from his recent work, Ecological Accompaniment: From Connectivity to Closeness in an Age of Loneliness: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-41800-6_14

Pope Francis and Laudato Si’

Theological attention to ecology has grown significantly, especially following Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Si’. This document calls humanity to care for our “common home,” recognizing the environmental crisis as a moral and spiritual issue. Pope Francis challenged us to see the interconnection of all life and calls for an ecological conversion of hearts.

Laudato Si’ highlights integral ecology, recognizing that social and environmental issues are intertwined. The suffering of the poor is often worsened by environmental degradation. Faith communities are called to address ecological concerns alongside social justice. When we harm the environment, we harm ourselves and future generations. Caring for creation is inseparable from caring for one another—a shared responsibility requiring solidarity and action.

Theological Engagement in the Healing of Our Common Home

Theologians such as Jürgen Moltmann emphasize the need for an “ecological turn” in theology. Fr. James Hanvey, SJ, echoes this call, speaking of a “biblical Sabbath of the land,” inviting Christians to participate in the healing of the earth through rest, reflection, and restoration.

Deepening theological engagement with ecology also invites faith communities to reconsider their liturgical practices. Some churches integrate environmental themes into their liturgies, celebrating the Season of Creation, blessing the land and waters, and using sustainable materials in worship. These practices reinforce that caring for the environment is an act of faith and gratitude for God’s creation.

Loneliness in Our Church and World

Ecclesial communities must also consider how affectivity—our emotional and spiritual responses—motivates ecological care. As Graham Ward suggests, praxis involves actions that both stem from and lead to faith. Ecological accompaniment fosters a connection with the earth and with God, making caring for creation a spiritual practice.

Beyond ecological responsibility, faith communities must respond to increasing loneliness, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic exposed physical, emotional, and spiritual vulnerabilities, deepening isolation. Studies show loneliness intensified, becoming a widespread and often stigmatized experience. This universal condition is further complicated by environmental crises, requiring a pastoral response.

A Theological Response: Ecological Accompaniment

Ecological accompaniment offers a pastoral response to both ecological degradation and human loneliness. This practice fosters spiritual healing and ecological restoration. Recognizing the divine presence in nature offers comfort, solace, and belonging.

Heike Springhart’s reflections on bodily vulnerability link human experience to Jesus Christ’s life and death. In this understanding, ecological accompaniment becomes an act of solidarity with both the earth and Christ’s suffering. Acknowledging our own vulnerability fosters empathy for the planet’s suffering and marginalized individuals.

Ecological accompaniment draws from the Christian tradition of accompaniment—walking with others in solidarity. In this case, the “other” includes suffering humanity and the earth itself. Christians are called to engage compassionately and attentively through personal actions, collective efforts, and prayer.

The Gift of Prayer in Times of Loneliness and Distress

To address loneliness, I propose prayer as a means of cultivating resilience through ecological accompaniment. Prayer reconnects individuals and communities with the earth and God’s presence within it. Contemplative prayer allows for reflection on loneliness and ecological disconnection while recognizing God’s sustaining presence in creation.

The Jesuit Examination of Consciousness offers a valuable framework. It encourages individuals to reflect on their day with gratitude, acknowledging moments of loneliness, vulnerability, and solace found in nature. This practice fosters awareness of how engagement with the earth nurtures body, mind, and spirit. One might pray for the grace to recognize how nature—through its beauty, rhythms, and life—offers resilience in times of isolation.

Conclusion: A Holistic Approach to Sustainability

This reflection proposes that ecclesial communities engage in ecological accompaniment as a spiritual and practical response to environmental and social crises. By embracing an expanded understanding of accompaniment—one that includes care for the earth and human vulnerability—Christians can foster a more sustainable and compassionate future. Through prayer, reflection, and action, faith communities can deepen their connection to the natural world and to one another. In doing so, they offer a path of healing for both the earth and the human heart, contributing to a more sustainable world.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Bridget Bowles is a third-year undergraduate student at the University of St. Michael’s College majoring in English and Christianity and Culture. Bridget works as a Student Campus Minister as part of the St. Mike’s Campus Ministry team, where she is proud to serve the spiritual needs of the entire St. Mike’s student body.

For me, university Easters have felt disjointed. With Holy Week falling in the middle of the exam period, the Triduum liturgies can feel like just another obligation after a long day of studying, and Easter Sunday with my family as a tentative afternoon of rest in between finals. The last three years, I have found myself attending the Triduum in a pew next to my backpack on my way from and towards hours of work at the library. The sense of celebration I want to feel at Christ’s resurrection becomes fleeting in a time of such stress. At Mass and at dinner with my family, I find myself thinking about a seemingly endless checklist of essays and exams. On the one hand, I feel guilty for not being fully present in such important moments, and on the other, I feel another guilt for spending so many precious hours away from my work at the busiest time of the year. From this guilt, a temptation arises for me to hyper-fixate on the suffering of Christ’s death on the cross over the triumph of His resurrection.

The temptation begins with how I see my own suffering reflected in that of Christ, but because I do not know what to do with my own guilt and stress, I cannot move on from it. Of course, the particularly minute– and it really is minute– suffering of students in the exam period is not the only reason that many of us feel this temptation to fixate on the pain of the crucifixion. We also see the greater sufferings of our own lives and of the world we live in reflected in Jesus’ suffering, and, again, not knowing what to do with such pain, we wish to remain stuck on Good Friday, never getting to Easter Sunday.

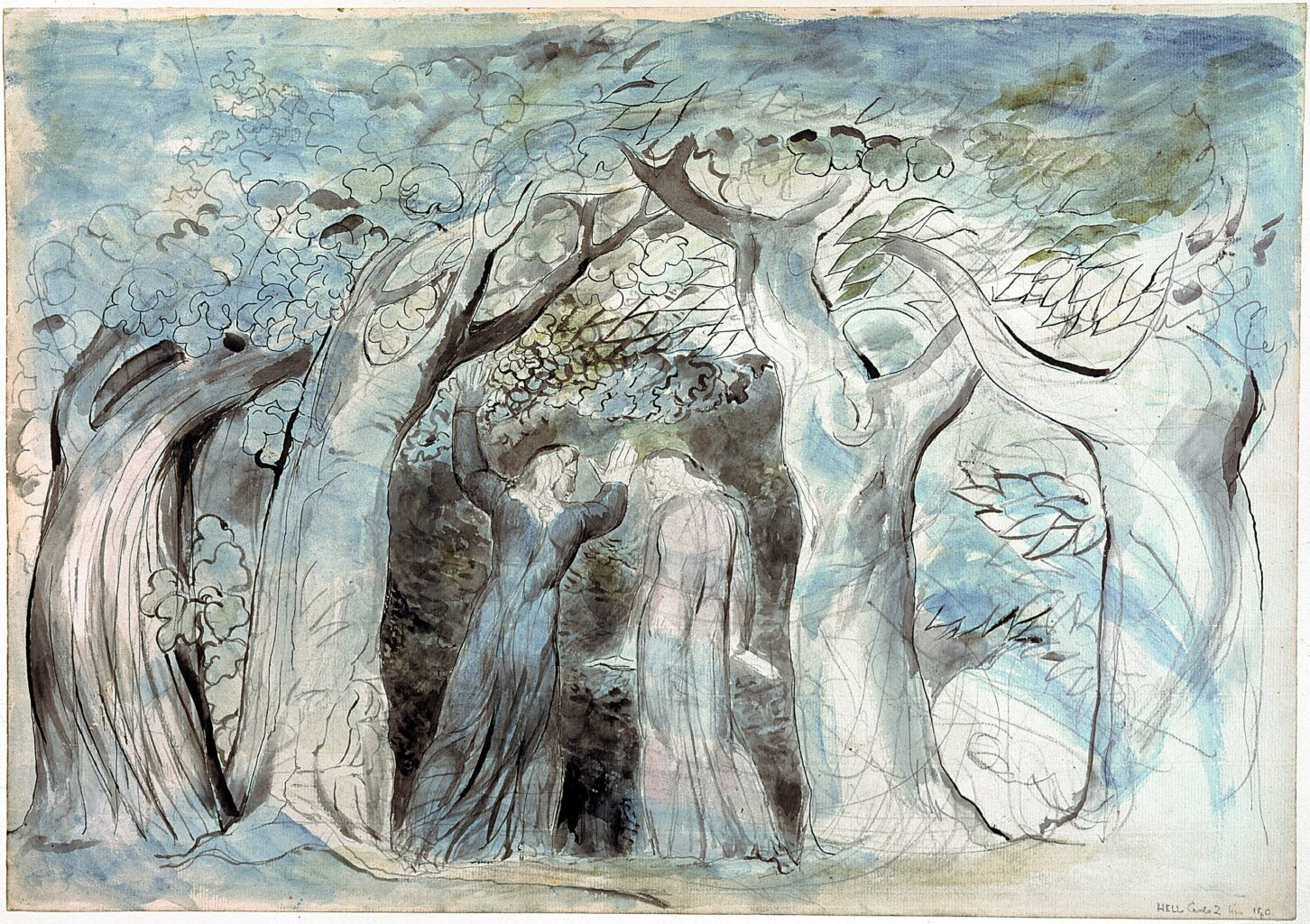

One way I have come to understand this phenomenon is through the relationship of Dante’s Inferno to the rest of his Divine Comedy. Generally speaking, most people, if they have read any part of the Divine Comedy at all, have only read Inferno. Pop culture loves the images of Hell and the outlandish suffering that Dante describes, and thus, there is a tendency to think of Inferno as entirely encompassing of Dante’s work, and yet there is still Purgatorio and then Paradiso. I led a reading group throughout this past academic year that was reading Inferno. At times, its suffering is fascinating; at others, it is difficult to comprehend. I first noticed a dissatisfaction developing from my tendency to hyper-fixate on suffering as I found myself at several points this past semester exhausted by Hell and ready to rush to the summit of Mount Purgatory. However, as Dante says, “the path to Paradise begins in Hell.” My reading group grappled with the duality of reading Inferno as both a necessity to understanding Purgatorio and Paradiso and also as one leg of a greater journey (an important leg, sure, but still only one aspect of the greater whole). I believe the same logic of how one should read Inferno in relation to the rest of the Divine Comedy can also be applied to how we feel about Good Friday in relation to the Easter Triduum or to how we feel about disjointed university Easters and the duality of both great stress and great celebration occurring at the same time in our lives. Jesus’ suffering is not only an experience of great agony but also a loving sacrifice. Yes, he is experiencing this very personal moment of intense physical pain, but he is experiencing such pain for the salvation of all humanity. He cries out, “My God! My God! Why have you forsaken me?” but also, as we hear this year in Luke’s gospel, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise,” and “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” These two experiences of Jesus on the cross are simultaneous and undifferentiated. His death is both suffering and redemption. To understand the place of the Triduum in our lives, we have to remember that, through Christ, there is always a hope for this same redemption in our own suffering. We want to hyper-fixate on suffering because we think that our fixation will allow us to know what “to do” with our pain (somehow, this seems easier than having hope), but we do not need to “know.” We need only to hope– to trust. For Catholics, Easter 2025 is particularly important because it is in a jubilee year. Pope Francis has declared the theme for this jubilee year to be “Pilgrims of Hope.” This Easter, in particular, we are being invited to reflect on the hope of Christ’s death and resurrection. Like Dante, our pilgrimage is one that need only traverse Hell to reach Paradise.

Inspired by Pope Francis and the jubilee year, my word of the year has been hope. Hope is not easy to have but keeping it as a persistent little voice in the back of my head has changed my outlook this Easter season. I am still stressed out and overwhelmed by essays and exams, but I am excited for Easter in a way I have not been in the last two years. My essays and exams will be written in due time, and I will take pleasure in celebrating in the hope to be found in Christ’s resurrection with my family, friends, and the entire St. Mike’s community. I will allow the realities of both suffering and celebration to be true just as they are, and I invite you all to do the same.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Evangeline Cowie (SMC 2T3) is a Special Assistant in the Senate of Canada, supporting the work of Senator Krista Ross. Previously, she served as President of the University of St. Michael’s College Student Union (USMCSU), leading advocacy and campus initiatives. She was also a member of the University of Toronto’s women’s rugby team. Evangeline holds an Honours Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Toronto and a Master of Arts in Political Science from the University of Ottawa. She remains passionate about public service and policy development.

Student government can be a stepping-stone for those interested in leadership or politics. For me, it was much more than that. It truly shaped my experience at St. Mike’s and at U of T.

I first joined SMCSU in 2021 as Vice-President of Mental and Health and Accessibility and transitioned to the role of President in 2022. I wanted to make a difference in the student experience at St. Mike’s, however small. I had the opportunity to work alongside talented and dedicated leaders, administrators, and students alike, all working towards the goal of improving our academic, social, and personal lives. At the time, I didn’t think very much about the impact that it would have on my future which, in retrospect, has been life changing.

My most important experiences came from the coordination and compromises that are necessary ingredients for collective team success. Within that framework, I learned to embrace disagreement as a way of diversifying my perspective. I learned how to adapt, problem-solve, and to approach new challenges with confidence and an open-mind. I also learned the importance of keeping the bigger picture in mind; maintaining a collaborative environment ensured that our team could truly make a positive impact. When a team works towards a common goal, it can accomplish great things.

I also want to give a shout-out to the value of clear, thoughtful, and tactful communication. Whether I was leading SMCSU meetings, or speaking with students and members of the administration, I found that our ability to reach the student body and to achieve our goals depended in large part on our ability to communicate effectively, in a manner that was relatable to our student body.

These lessons have continued to inform my daily work at the Senate of Canada. Transitioning to this venerable institution was certainly a robust learning curve but one that I felt well-equipped to handle with the bank of skills that I developed through my work with SMCSU. The essence of Senate’s work is, in its purest form, to give a voice to regional and minority views that might not have been accounted for in the legislative process and communicating them clearly back to the House of Commons. As an institution of “sober second thought”, the Senate espouses diversity, teamwork, and effective communication. I can’t think of a more perfect “prep school” for my work than my experience with SMCSU.

In addition to all I have said, I believe that the most valuable takeaway from my time at St. Mike’s has been the importance of community. St. Mike’s taught me that there is strength in being part of a team, in supporting others and learning from those around you. Even on my last day as SMCSU President, passing the baton to another set of incredible student leaders, I was reminded that we were all part of a long history of students giving of their valuable time to improving our college, our home. It is a similar feeling to the one I have most days working in the Senate; that my contributions are part of a long history of talented individuals dedicating their time to having an impact, small or large, on the governance of our country. I feel incredibly fortunate to have the opportunity to contribute to the work of Senator Ross and to take part in the feeling of community that comes along with it.

As I write this from my laptop, which is still covered in St. Mike’s paraphernalia, I take pride in knowing that I will always be part of the St. Mike’s family. While I hope to have had a positive impact, however small, on the St. Mike’s community, the St. Mike’s community has left an inedible mark on me.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Angie MacAloney-Mueller has worked on the St. Mike’s campus for more than 30 years. She currently serves as the physical plant coordinator. She has been an avid birder for more than 20 years, often venturing out with her husband Rob, who took the blackbird photo above.

To some he’s a menace, to others, he’s a marvel of nature. He is the male red-winged blackbird.

If you’ve been around Elmsley Hall during nesting season, which is in the late spring, you may have been swooped by this doting father. The male red-wings usually arrive here in March or April, after travelling hundreds–and sometimes thousands– of miles. They arrive early to find potential nesting spots and claim their territory.

The females arrive four to six weeks later, and the boys must impress and fight for a female’s attention and woo her to his territory. Once a female chooses a male’s territory, she will build the nest. She incubates the eggs for 11-12 days, and the baby birds fledge about 10 days after hatching. The male will feed the female during incubation and also assist in feeding and raising the young. Male red-winged blackbirds are fiercely protective of their nest and young, swooping at anything that gets too close, no matter the size.

As a longtime birder I have a lot of respect for the red-winged blackbird. For me they are the real sign of the arrival of spring. American robins are here year-round now, often flocking up together to survive the colder months. I once saw a red-winged blackbird swoop at an eagle on the Toronto Islands. The eagle there, or we humans on campus here, have no interest in disturbing his nest, it’s actually illegal to disturb a migratory bird nest, but he’ll do what is instinctive for him to do: protect. The males spend many hours a day watching guard over their nest site. I’ve often seen him keeping watch from the roof of Elmsley Hall or Charbonnel Lounge.

I know it can be startling to be swooped. My advice is to not react; just keep walking, don’t run or scream. If you can, make eye contact with him. He may be protective, but he’s a bit of a coward, too. I do believe we can co-exist for a couple of months while they raise their young before migrating south before the summer ends.

The question I’ve been asked most about the campus red-wing is, “Is it the same bird?” I don’t know, but it could be. The oldest one on record was over 15 years old. He was found hurt but was able to be released after recovering. If it’s not the same bird, it’s most likely one who was hatched here.

The unusual thing about these birds returning here year after year is that our grounds are not their preferred habitat. They usually prefer marshy areas and wetlands, nesting in the cattails. I guess they discovered our campus is an oasis in the city as well.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Simon Burke is a recent graduate of St. Michael’s Diploma in Interfaith Dialogue. Originally from Dundee, Scotland he grew up in Wallaceburg, Ontario. He is a longtime public servant, having held senior offices within the Canadian and Ontario governments and in university administration. Over the course of his career he led consultations that resulted in comprehensive legislation for persons with disabilities, prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation, civil liberties protections during emergencies, restorative justice systems to better meet the needs of victims of violent crime and the priorities of First Nations communities. He has served as Director Ethics in the Ontario Public Service, Director of Ontario’s Pay Equity Commission, Director of Policy to Canada’s Minister of Global Affairs and was the Senior Executive Officer and Chief Administrative Officer of the Criminal Injuries Compensation Board. He was responsible for the operational and governance reviews of the Ontario Parole Board, the Ontario Civilian Police Commission and the Ontario Trillium Foundation. He is a Board Director with the Catholic Congregational Legacy Charity and Catholic Health Sponsors of Ontario which provides sponsorship to 22 health care organizations originally established by seven congregations of religious Sisters. The Sisters were health care pioneers who created a culture of compassion to prioritize serving the vulnerable and those most in need.

When there was a lot more snow on the ground, recent graduates of the Diploma in Interfaith Dialogue were asked to get together with Roxanne Wright, Manager of Program Development and Delivery, Continuing Education, to discuss our learning experience with the diploma. Kudos to St. Mike’s for wanting to further develop this new, important and much needed offering — and making it more widely accessible.

Pursuit of self-knowledge is the critical feature of a university’s aims and objectives and this program at St. Mike’s has embraced the study of our community’s cultural and faith communities and their interactions. Those able to attend the evening conversation with Roxanne were happy to help because the value of the program and its founding sponsor, Scarboro Missions, is so self-evident — knowledge about our faiths can be and should be put at the service of our society to respond thoughtfully and effectively to practical problems. Indeed, Pope Francis in his recently published “Fifteen Rules for a Good Life” offers that Rule #4 is to believe in the existence of lofty and beautiful truths. He may well have been referencing interfaith dialogue when noting that “…the world moves forward thanks to men and women who broke down walls, built bridges, dreamed and believed….”.

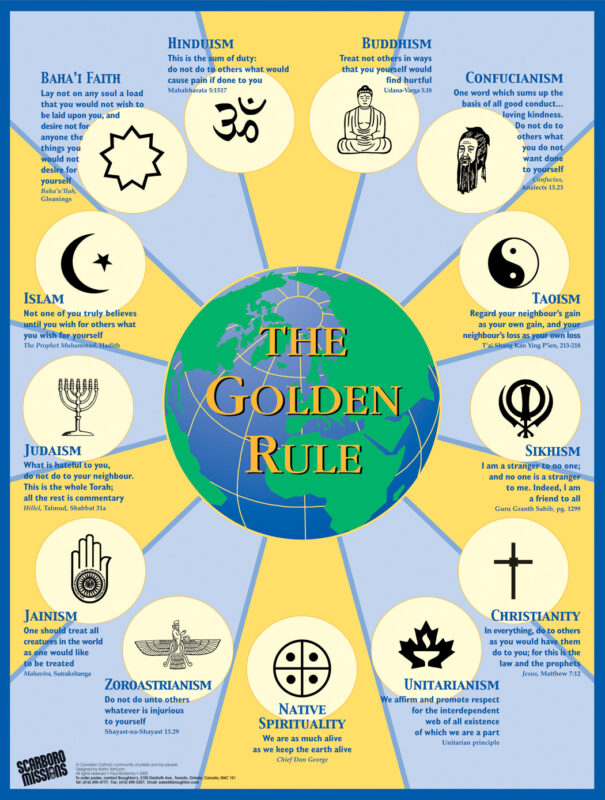

It is quite fitting that the University of St. Michael’s College, an important Canadian and Roman Catholic institution at the centre of one of the most multicultural and multi-faith city in one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world, offers a continuing education program that engages learners with a deeper understanding of Catholicism and with leaders from many of Toronto’s faith communities (Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Indigenous, Muslim, Judaism, Sikh). The program is straightforward. Students learn about the foundations of each faith tradition and its practices. The origins, the central teachings, the denominational practices, and social and political influences of each faith community are considered with care and respect. Courses benefits from engagement with experts, scholars and trained practitioners of interfaith encounters. For example, the course on Sikhism included a wonderful class trip to a Gurdwara where we were generously welcomed and very well fed. All this learning is delivered usefully within the framework of a comparative perspective.

In discussion with Roxanne there was a clear consensus that the program is a timely survey of the tenets of religions and religious practices with valuable emphases on similarities and differences. More strongly expressed was that the program is an important platform for Catholics as well as persons from other faiths (or none at all) to develop a deeper appreciation of the shared values of many faiths – ‘The Golden Rule’.

Moreover, courses offer a critical perspective on the value-add that dialogue between people of differing faiths can play in better understanding themselves in relation to peoples of different faith backgrounds. In short, the program awakens participants to the histories of faiths and equips people with an essential cultural competence. Developing practical competencies to structure meaningful connections between peoples of different faiths can bridge differences and encourage understandings. Surely our neighbourhoods and indeed our world need more understanding — not less — of others. The program points to a path less travelled where we can engage with peoples outside our own communities. Essentially, the program serves up a framework for listening and for learning so we can respectfully meet, greet and, one hopes, protect each other.

Over a two-year period I was able to participate in classes exploring issues associated with the fraught histories of religion and world migration, inculturation, mysticism, and women and religion. I feel fortunate to have taken classes in Islam, Judaism, Buddhism and Sikhism, especially during a time fraught with such tension and such sorrow. More often than not lectures led to well-considered class discussions facilitated by the practical contributions of guest lecturers, including religious leaders, elected officials, community advocates, teachers and senior leaders in the not-for-profit sector.

I feel quite lucky to have spent several Monday evenings in the company of others discussing the problems and prospects of interfaith dialogue to strengthen solidarity with human rights, human dignity and the common good. For me, the lectures and experiential learning opportunities that had Nostra Aetate at their core (the 1965 proclamation made by His Holiness Pope Paul VI entitled the ‘Declaration on the relation of the Church to non-Christian Religions’) were highlights. Doctoral candidate Mia Theocharis in ‘Catholic Perspectives on Ecumenical and Interreligious Dialogue’ got us to think deeply and critically about our personal roles in bringing to life the idea that the Catholic Church “…rejects nothing that is true and holy in [non-Christian] religions.” Dr. John Sampson’s curated lectures on inculturation were comprehensive assessments of the Church’s declaration of reverence for “…those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings which, though differing in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all men.”

The program was a good fit for my learning needs. In my role as a board member for a Catholic healthcare and social services organization with a mandate to further the “healing ministry of Jesus” knowing about the principles and practices and necessity of interfaith dialogue in Canada is a critical requirement. Truly responding to the needs of people and communities who have experienced or are experiencing marginalization, oppression and discrimination requires listening skills both at the personal and institutional levels. St. Mike’s has offered me an appreciation for the value of interfaith dialogue and its associated mechanisms to bring people together, build relationships and foster partnerships for the common good.

The Diploma in Interfaith Dialogue is open to all and accepts applications throughout the year.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Rhea Raghunauth is a fourth-year Bachelor of Science student at the University of Toronto, majoring in Neuroscience and Public Health. During her undergraduate studies, she became deeply aware of the lack of advocacy and education surrounding gender-based violence, despite the rising rates of intimate partner violence and femicide in Ontario and her hometown of Brampton. This realization fueled her commitment to driving change through advocacy and education, both within the university and her community. Combining her academic background with her passion for community building, Rhea aims to challenge and reshape the discourse on gender-based violence, with a particular focus on intimate partner violence.

Living in a city like Toronto is undoubtedly exhilarating. The skyline, the beautiful CN Tower, the late-night food spots in Chinatown, the hum of people moving in all directions—it’s a world that feels alive. A world that is so rich in culture, history and stories. But for women and gender-diverse people, city life isn’t just a predominantly positive place; city life comes with an undercurrent of caution, a silent set of calculations we make every day just to exist safely.

Walking home after dark? Share your location. Wearing headphones? Keep one ear open. Walking to class? Find a friend. Wearing a dress? Maybe change. These are the unspoken rules of survival for women. These are the rules that aren’t written in any city guide but are learned through experience, through whispered warnings from friends, through the stories of those who didn’t make it home safe.

These habits may seem small, but they reflect a deep-rooted societal issue: Women are expected to be responsible for their own safety in a world that refuses to guarantee it. And while the beautiful city promises boundless possibilities, career opportunities, and educational endeavours, it also harbors spaces of exclusion, where fear dictates movement, choices, and even ambition. The ability to explore freely, to take up space without hesitation, remains an elusive privilege, afforded by only some.

Despite the tremendous strides women and gender-diverse people have taken toward challenging inequalities and inspiring change, gender-based violence remains, unfortunately, an urgent issue. The devastating reality of gender-based violence has forced the public to encourage women to employ specific tactics to evade the tragedies of gender-based violence. We’re often told to “be careful,” to change how we dress, to avoid certain places at certain times. It is always up to us to be careful and make the right and safest decisions. These tragic narratives that strip women of their autonomy have been further accentuated by sociopolitical turmoil, with phrases like “your body, my choice” and “get back to the kitchen” dominating social media. These harmful messages are reinforced through television, video games, and everyday conversations. When these concerning behaviors are called into question, they are often dismissed with phrases like “boys will be boys.”

But these harmful excuses are not just a silly tactic to dismiss problematic behavior—they reinforce a culture that normalizes gender-based violence. When young boys grow up hearing that their actions, no matter how aggressive or inappropriate, are just “boys being boys,” they internalize a dangerous message: that accountability does not apply to them. Meanwhile, women and gender-diverse people are conditioned to accept discomfort, to shrink themselves, and to modify their behavior in ways that prioritize the comfort of others over their well-being.

The problem with this logic is that it shifts the burden of prevention onto potential victims rather than addressing the root cause: the perpetrators and the systems that enable them. Instead of teaching women and gender-diverse people how to avoid danger, why aren’t we focusing on raising boys and men who do not pose a threat in the first place? Why aren’t we challenging the structures that excuse predatory behavior and, instead, creating environments where everyone can exist without fear?

The reality of gender-based violence is grim, but there is hope. Across the world, movements are pushing for change – consent education in schools is growing, conversations about toxic masculinity are becoming more mainstream, and more survivors are speaking out than ever before. These shifts matter. They disrupt the silence that allows violence to thrive.

However, this is not enough. We need systemic accountability. Governments and policymakers must strengthen protections for survivors. Workplaces, universities, and public institutions need to actively implement policies that ensure safety and justice. The media must be held responsible for the messages they amplify, restricting and abolishing the narrative of men dominating women.

And men, especially, need to step up—not as silent bystanders, but as active participants in dismantling the very structures that allow gender-based violence to persist.

Toronto, like any city, holds incredible potential. It can be a place of opportunity, of empowerment, of safety—but only if we commit to making it so. The unspoken rules of urban survival should not exist. Women and gender-diverse people should not have to plan their lives around fear. And the responsibility for change should not rest solely on those most at risk.

While we celebrate the tremendous achievements of women on this International Women’s Day, we must also Accelerate Action and advocate for the strides yet to be made. It’s time to rewrite the narrative. Not just with words but with action.

The University of St. Michael’s will mark International Women’s Day on Saturday, March 8.

Rhea Raghunauth is the recipient of a University of Toronto Student Leadership Award for her work as a mentor with U of T’s Women’s Advocacy Outreach, Co-President of the Mental Health Association at U of T, and Co-Founder of The Canadian Courage Project UTSG Chapter. In the later role she led a book drive by collecting hundreds of donated books to start the first in-house library at HomesFirst Shelters. Through all her involvement, she has discovered a passion for advocacy and volunteering.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Hi everyone, I’m Doyin, and I’m a student studying Cell and Systems Biology, currently in my Co-op year. As someone passionate about student life and community building, I serve as a Residence Don at St. Mike’s Residence, Education and Outreach Director for the Black Students Association, and Vice President of International Community Outreach for the St. Michael’s College Student Union.

I’m excited to share with you our upcoming Culture Week here at SMC. As an international student at U of T, I’ve been fortunate to experience the diverse student body and multicultural environment, especially since the university is located in the heart of Toronto. This city, with its vibrant cultural scene, has allowed me to make friends with people from different backgrounds and learn about their experiences.

Growing up in Lagos State, Nigeria, which shares similarities with Toronto as a large city, I’ve always been exposed to diverse cultures. Nigeria, with its 36 states and numerous ethnic groups, celebrates the beauty of different cultures, so it’s no surprise that I thrive in such environments. I understood the importance of feeling connected to my background early on. When I joined U of T, I actively participated in the Nigerian Student Association and the Black Student Association to feel a sense of community. However, I didn’t limit myself to just these groups; I also sought opportunities to learn from and immerse myself in different cultural backgrounds from around the globe. Working as an International Student Experience Ambassador for the Centre for International Experience at U of T was an incredible opportunity that taught me a lot about the challenges and triumphs of international students. It also gave me a deeper understanding of the resources available to support students in navigating cultural differences and building a community away from home.

Naturally, when nominations opened for the 2024-2025 term of the SMCSU, this position felt like the most natural fit for me, given my extensive background and knowledge of the international community. As Vice President, I prioritized exposing students to U of T’s resources to make their transition smoother, especially through the Centre for International Experience, and promoting more community among international students. This initiative has been successful so far, with our first Cultural Week last semester featuring a fun cultural trivia night, cultural arts and crafts, and an international student mixer. These events not only brought students together but also provided a platform for cultural exchange and learning.

I approach every experience with an open mind, eager to learn and gather new experiences. This semester, we have Culture Week 2.0, a collaboration with several student groups and clubs. From March 4-7, we have an exciting lineup of events designed to celebrate the rich cultural diversity of our community. Here’s a sneak peek at what we have planned:

- Cultural Arts and Crafts: Explore traditional crafts from around the world and create your own cultural masterpiece.

- Iftar Dinner: Join us for a special dinner to break the fast during Ramadan; open to all students regardless of faith.

- Pierogi Making: Learn the art of making traditional Polish pierogi and enjoy a taste of Eastern European culture.

- Guess the Country Games Night: Test your knowledge of global cultures in a fun and interactive game night.

- St. David’s Day Celebration: Celebrate Welsh culture with music, food, and festivities.

We’re working with various student groups to bring this event to St. Mike’s and celebrate diverse cultures while gaining new experiences. Whether you’re an international student or just curious about different cultures, Culture Week 2.0 is the perfect opportunity to connect with others, learn something new, and have fun. So mark your calendars for March 4-7 and join us for an unforgettable celebration of global cultures!

Read other InsightOut posts.

Cynthia L. Cameron is the Patrick and Barbara Keenan Chair of Religious Education and Associate Professor of Religious Education at the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology. Her research focuses on adolescents, particularly female adolescents, in developmental psychology, Catholic theological anthropology, and practices of Catholic schooling. Among her recent work is Nobody’s Perfect: Adolescents, Mistake-Making, and Christian Religious Education, co-edited with Lakisha Lockhart-Rusch and Emily Peck (Fortress Press, 2025) and“Genders, Sexualities, and Catholic Schools: Towards a Theological Anthropology of Adolescent Flourishing,” published in the British Journal of Religious Education. Prior to coming to Regis St. Michael’s in 2021, she taught at the undergraduate and graduate levels in the United States and had a nearly 20-year career as a teacher and administrator in Catholic high schools.

In 2021, I accepted the offer of a faculty position at the University of St. Michael’s College’s Faculty of Theology (now the Regis St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology) and moved from the Boston area in the United States to Toronto. And I am very grateful that I did. I love the work that I do and the people I get to do it with. I have also been delighted to find myself living in Canada, in Toronto particularly.

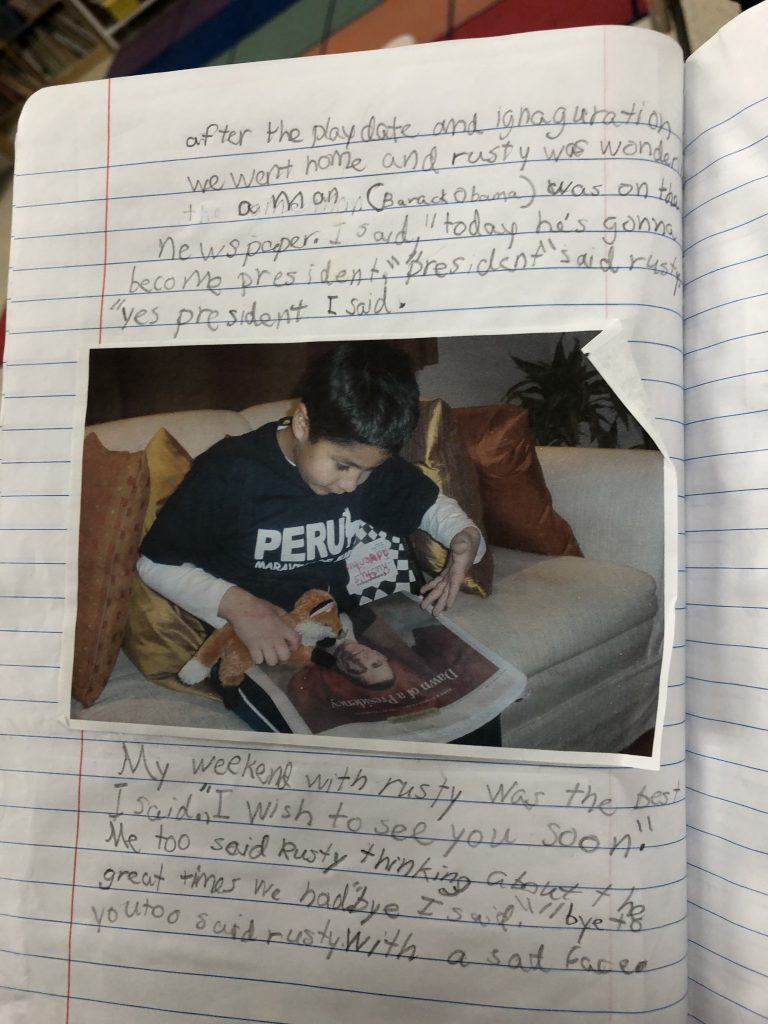

In recent weeks, since the presidential inauguration in the United States, I have found my delight to be tempered. This is not to say that I am any less grateful to be living in Canada. But witnessing the drastic upheaval of the federal government under the new administration, a profound reminder of the fragility of our democratic institutions, makes me deeply sad. I am angry and disappointed, too; but sadness is the overwhelming emotional response that I am sitting with these days.

In his helpful and now-classic exploration of what it means for the Christian church to be prophetic, the biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann calls us to nurture an alternative vision of the world, one that critiques and challenges the dominant culture. Particularly helpful in Brueggemann’s analysis is his naming of two parts to the church’s prophetic task. Lament and hope. What I find helpful in Brueggemann’s approach is his acknowledgment that lament is an important part of the prophetic task of the Christian church. As a community of people striving to live more and more into the Reign of God, we need to attend to the sadness and grief that people experience in the face of injustice, oppression, and death. Lament then can lead to an energizing hope, one that is critical and realistic, but only if we first acknowledge our grief. So, what’s helpful for me in Brueggemann’s work is the affirmation that sadness (and anger and disappointment) are appropriate responses to the kinds of social disruption that I am seeing.

It is also profoundly weird to be both an insider and an outsider to these events. As a U.S. citizen, I am impacted by and participating in the upheaval. I know LGBTQ kids who are now living in fear for their lives. A friend who lived out their Christian vocation to provide food for the hungry has lost their job with USAID. I am no longer certain that my 87-year-old father will get his social security check each month. I assume that my financial and tax information has been accessed by unauthorized actors. At the same time, I am living in Canada, where things like pensions in old age, the protection of LGBTQ rights, and the care for the poor are still happening. Certainly, in imperfect ways and in ways that could (and should) be improved. The state of things in the U.S., however, is a reminder to me of how quickly we can lose the institutions that we thought could protect people.

But the basic assumption that a society has a responsibility to care for the vulnerable amongst us still seems to be a value in Canada. In Catholic Social Teaching, this assumption that we have a responsibility to attend to the needs of our vulnerable siblings is named as the preferential option for the poor. It is the insistence that the creation of a more just society requires the prioritizing of the needs of those most at the margins of that society. It is the affirmation that we cannot live into the Reign of God – or, better, the kin-dom of God, as the theologian Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz puts it – unless we are prepared to place the poor and vulnerable at the center of our attention.

This commitment to the vulnerable amongst us is something that I still find in Canada. And, while my sadness (and anger and disappointment) at what is happening in the U.S. remains, Canada does give me hope. And, for that, I am deeply grateful.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Hi, my name is Ronda Burchartz. I feel truly blessed to have earned my Master of Religious Education degree from the Faculty of Theology at University of St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto. My journey has taken me through many roles/responsibilities—student, truck driver, fitness instructor, teacher, and now a flight attendant for adventure travellers and scientists. But beyond any title, Who I am is created by Love, to Love, for Love. I strive to bring that spirit into every role/responsibility: as a daughter, wife, mother, service provider, caregiver, friend, student or colleague. My Master’s studies helped me understand that our essence matters more than any title we hold. I hope the story below reflects that truth.

There’s cold, and then there’s Antarctica. My office is a plane, my home is a tent on a glacier, and my job as a flight attendant takes me to some of the most extreme places on Earth. But once the Antarctic Bug bites, there’s no going back—you find yourself drawn to the ice over and over again.

Flying in the Harshest Conditions

Being a flight attendant in Antarctica is nothing like other commercial aviation; it is more personal, and one must be ready for anything. Our flights depend on the weather, with brutal winds and icy runways making every journey unpredictable. There are no luxury lounges or in-flight entertainment—just a crew that depends on each other for everything, from safety to sanity.

Landing in the middle of a vast, white expanse never loses its magic. The ice stretches endlessly, shimmering under the 24-hour sun that never sets. But as breathtaking as it is, this environment is unforgiving. When we land, there are no terminals—just a frozen runway and the realization that we’re in one of the most remote places on the planet.

The guests depend on us when landing in these conditions. They look to us for reassurance, especially when touching down on snow-covered runways using skis. Sometimes, the landings are hard or bumpy, and guests glance back at me as if to ask, “Is everything okay?” I reassure them it is, and once we stop and step outside, they’re grateful to have had such a skilled crew looking after them.

The aircraft cabin is my home away from home. When guests come on board, I treat them as guests in my home—offering hot drinks and snacks and listening to their incredible stories. The people we meet are fascinating, and I am grateful for the opportunity to host so many outstanding individuals. One time, we were hosting a group when one of their family members fell ill back home. I offered comfort with hot drinks, and one of the guests asked me to lead a prayer circle for them. At that moment, I felt like part of their family. Their warmth and kindness stayed with me—I hope to meet them again.

Life on a Glacier

When not flying, we live in tents on the ice, completely exposed to the elements. The wind howls relentlessly, rattling our temporary homes, and the cold seeps into everything. But despite the harsh conditions, our tents are our refuge and sanctuary. There’s a sense of camaraderie that makes it all worth it. Our crew is more than just a team—we are a family, looking out for one another in one of the harshest environments imaginable.

We rely on each other not only for survival but also for emotional support. When we have losses at home that we cannot return for, we listen to and care for each other. One of our dear friends lost his mother the day he arrived, and there was no way to get him home for a month. So, we helped him by listening to his stories and being someone, he could count on. In such an isolated place, these small acts of kindness mean everything.

Simple things, like sharing a hot drink or swapping stories after a long day, become moments of warmth in the freezing cold. The Antarctic has a way of forging unbreakable bonds, which keeps many of us returning.

Meeting the People Who Call Antarctica Home

One of the most fascinating parts of this job is meeting the people who choose to live and work here for one year to eighteen months on the ice. Our flights take us to scientific bases where researchers dedicate their lives to studying Antarctica’s ice, climate, and unique wildlife. These scientists and explorers have an undeniable passion for the continent, and their stories are as awe-inspiring as the landscapes around us.

Our trips include flying to Atka Bay to see the emperor penguins—I can see these majestic birds at least seven times each season. On these trips, we’ve had the privilege of watching baby emperor penguins huddle together for warmth, their fluffy bodies braving the elements. It’s moments like these that make the hardships worth it—the chance to witness nature at its purest and most untouched.

Our team also flies to the South Pole at least five times per season. It is brutally cold there, and on the way back to our tents at Wolf’s Fang, we must stay at Dixie Camp for the night in unheated tents, where the temperature is never warmer than -20°C. Undressing and getting into the sleeping bag on those nights is a struggle, but once inside, we are toasty warm. Then we must get out in the morning… brrrr!

The Call of the Ice

Despite the extreme cold, the relentless winds, and the isolation, there’s something about Antarctica that gets under your skin. The sheer vastness, the beauty, the adventure—it all calls you back. Many of us come here thinking it’ll be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, only to find ourselves returning year after year.

That’s the power of the Antarctic Bug. Once it bites, you’re hooked for life.

Read other InsightOut posts.

Student Neve Chamberlain is the director of the SMC Troubadours’ production of The Shawshank Redemption.

Putting on The Shawshank Redemption has been a very ambitious project for us. We knew we wanted to make Shawshank feel as real as possible while also respecting the stage as our medium, but the stage has limitations. We had to get creative. Our aim was not to just copy the film. This was going to be our version of The Shawshank Redemption.

We decided to dedicate most of our budget to building the set – a giant prison that spans the full Hart House stage, acting almost as character of its own. We thrifted most of the costumes, handmade many of our props, and decided to rely heavily on lighting and our soundscape.